“Black girls are magic!” professed CaShawn Thompson in early 2014, spurring a movement of empowerment and celebration. Now there’s an online literary magazine bearing the same name, but with one problem: Thompson has nothing to do with it.

The magazine, “featuring speculative fiction by and about black women,” according to its website, was started by writer Kenesha Williams. Its first issue has not yet been published, but already it’s making waves in the black literature community based on the name alone.

Prominent blogger and activist Feminista Jones, a friend of Thompson’s, shared her outrage on Monday night. She is certain that Thompson (@thepbg on Twitter) is widely credited as the originator of the phrase and hashtag #BlackGirlsAreMagic, and that Williams’ publication should have known better.

https://twitter.com/FeministaJones/status/641013210200567808

https://twitter.com/FeministaJones/status/641013578020073473

She’s even calling for Williams to scrap the name altogether.

https://twitter.com/FeministaJones/status/641016972646477825

“Black girls and women made power moves in every arena, from arts and entertainment, to sports, to activism. We showed up, showed out, and proved just how influential our magic is and how we can use it to change the world,” Jones wrote in 2014 of Thompson’s movement in connection to the many accomplishments that year by successful black women such as Lupita Nyong’o, Shonda Rhimes, Kerry Washington and Viola Davis.

Thompson also took to her own Twitter to express her dismay about the literary magazine’s failure to consult her. She gave some indication as to how she plans on handling the matter and stands by the assertion that #BlackGirlsAreMagic is a product of her own hard work.

My daughter just texted me about this #BlackGirlsAreMagic fiasco & told me to "be bold." So that's what I'm gonna do.

— Miss Shawn! FKA @thepbg (@MsCaShawn) September 8, 2015

As much as I LOVE sci-fi & Black Girls, I would have been @BlkGirlMagicMag's biggest supporters if it had come down the pike better. But,no.

— Miss Shawn! FKA @thepbg (@MsCaShawn) September 8, 2015

I expect ppl to latch on to #BlackGirlsAreMagic. I wanted that to happen. But damn, give credit where credit is due.

— Miss Shawn! FKA @thepbg (@MsCaShawn) September 8, 2015

And DON'T try to make a dime or a name off my work. And yes, #BlackGirlsAreMagic has been work.

— Miss Shawn! FKA @thepbg (@MsCaShawn) September 8, 2015

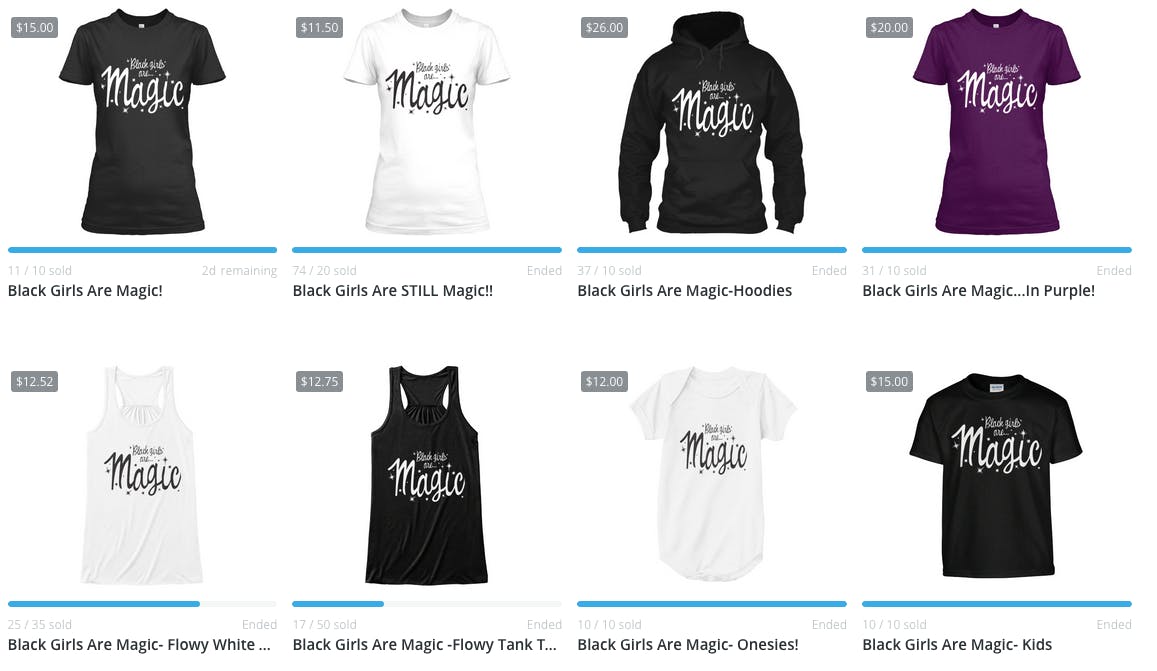

I need to sell more shirts so I can pay for the trademark process. #BlackGirlsAreMagic #BeBold

— Miss Shawn! FKA @thepbg (@MsCaShawn) September 8, 2015

These are the t-shirts she references, which have become a cornerstone of her efforts to empower black women.

“I started #BlackGirlsAreMagic to honor the Black women in my family and all around me that I saw doing incredible things, so much so that they appeared to be magical to me,” Thompson wrote in an email to the Daily Dot. “The t-shirts that I sold helped me and my children out in a time when I really needed it, but more than that, the hashtag has been one of love and community-building for Black women online. I’m proud of how it has spread and been received, but it is also representative of my innovation and my work.

She also noted that “if she [Williams] had approached me earlier and asked me to be a part of it, I probably would have declined to write but would have seriously considered endorsing the lit mag and spreading the word. It actually is an idea that I would support.”

As for the trademark issue, Thompson says she hasn’t had the time or money to trademark the hashtag but admits, “I see now that it is a necessary investment.”

Williams, for her part, denies any ill intentions, and says she was unaware of both Thompson and her role in starting the #BlackGirlsAreMagic hashtag. When the Daily Dot reached out to her for comment, she directed us to a post on blackgirlmagicmag.com called “On the name of my magazine or how my Twitter mentions ended up in shambles.”

She writes of how she’s been villainized because of the name of her project, and how her research did not return any definitive results when she tried to pinpoint the origin of the phrase.

I don’t remember the first time I heard Black Girls are Magic, but I do know that it has been floating in the ether for a while. My cursory Google search of the phrase Black Girls are Magic produced a handful of T-shirt sites (1) (2) , Even popular Black website Blavity, the site for Black Millennials, sells Black Girls are Magic T-shirts. There are also countless media references (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) and Tumblr pages celebrating Black female beauty and style. So, it’s very easy to see how someone could walk away from the search thinking, ALL CLEAR this is a communal phrase. So, after searching, I then looked up the URL and it wasn’t owned currently or in the past by anyone and was available for purchase. So, I purchased the URL and began doing the groundwork for a venture that I feel is needed and desired by many.

After people began accusing her of co-opting Thompson’s work, she says she posted on her Twitter account (which is now private) that she’d be happy to have Thompson write for her in a paid capacity. This, too, she says, was ripped to shreds.

In the excitement of starting something new and the demands of life (three young children) along with a holiday weekend, I didn’t have the time I thought was deserved of a conversation with her and put it on the back burner until the holiday was over. However, last evening, I came back to a firestorm of Twitter mentions over this issue. I unwisely have tried to argue my side on Twitter. Twitter isn’t the place for that at all. There is only so much you can put in so little space without someone taking it in a way you didn’t intend, which is why I’m addressing it here.

She references the #BlackLivesMatter as a similar sort of situation—a hashtag that spurred a powerful movement and many different offshoots. But she feels she’s been the target of extreme vitriol. She writes, “I never intended to step on anyone’s toes, at all.”

But whether or not Thompson should have trademarked the hashtag, or will be able to in the future, some believe that’s not the point. Novelist Rashid Darden, on his blog Old Gold Soul, wrote the following:

Kenesha, sis. You have a great idea here and I do believe a speculative fiction literary magazine with women and girls as protagonists is necessary, amazing, powerful, and absolutely on time. And I know that literary magazines are not money-making ventures. They are labors of love that (God-willing) get your name out there as the arbiter of new fiction, and “put on” new authors who might not be featured anywhere else due to sexism and racism in mainstream genre publications.

But you have got to change the name.

This is not a trademark issue. This is an issue of sisterhood.

This isn’t about what you’re allowed to do. We’re legally allowed to do a lot of things. But this thing? This thing you shouldn’t do.

And others are calling for writers to consider the facts before they submit to Williams’ venture, which pays $50 per post and will soon be launching an IndieGoGo campaign so that writers can get even more.

The lit mag used "Black Girls are magic" without asking @thepbg. Just wanted to point it out in case it impacts your willingness to submit.

— Tina Vasquez (@TheTinaVasquez) September 8, 2015

https://twitter.com/SaudaAinra/status/641070373900013568

@dlwill98 Ugh. It turns out this literary magazine has nothing to do with the real Black Girls Are Magic. Proceed with caution.

— Renee Antoinette (@ReneeAntoinett2) September 8, 2015

Williams ended her post by saying that she has reached out to Thompson and hopes they can work this out amicably.

“And for those that believe that this was handled poorly by myself,” she wrote, “blame my head and not my heart.”

Photo via Realsistas/Instagram