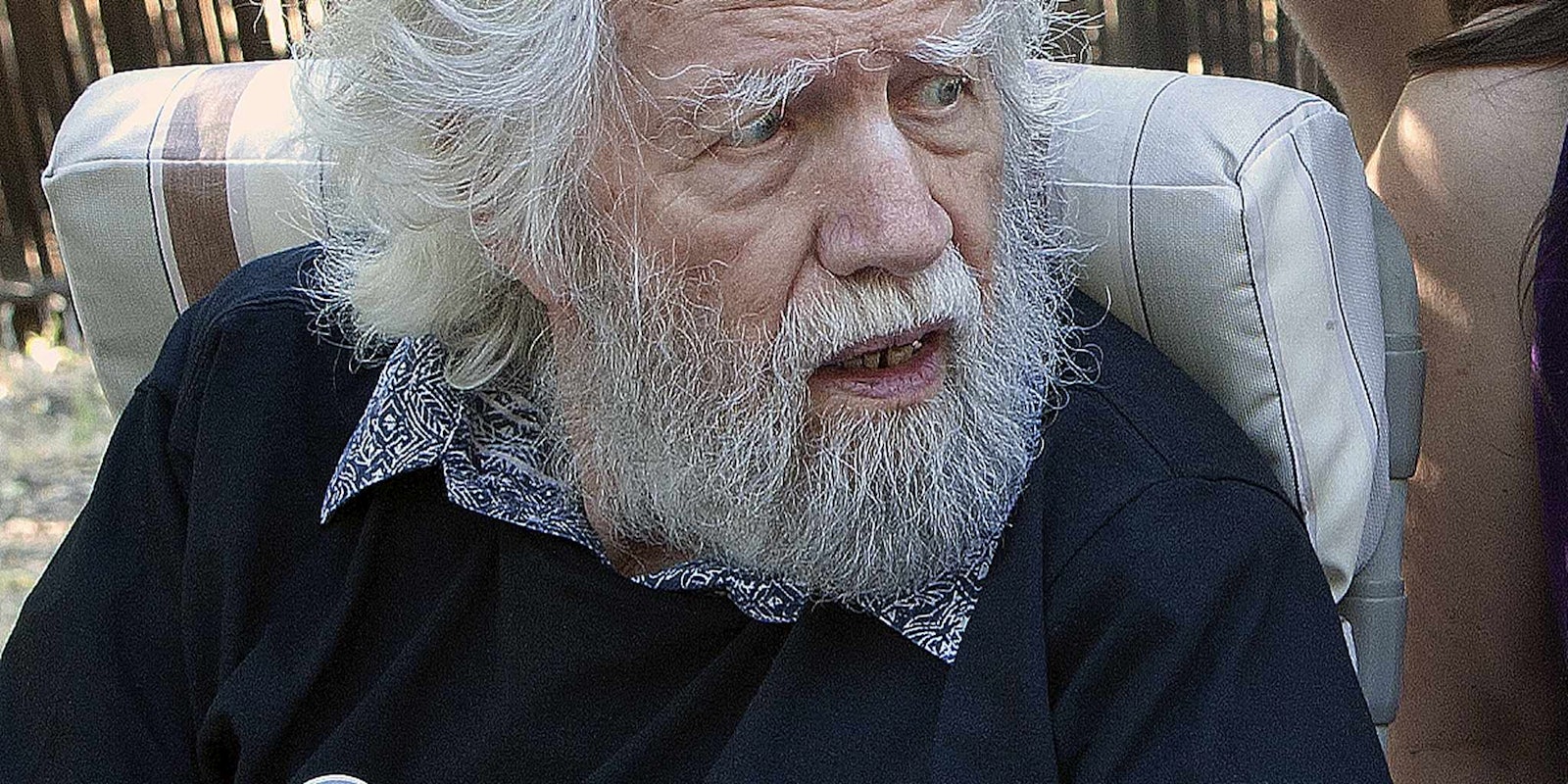

This week, Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin, known as the “Godfather of Ecstasy,” passed away at the age of 88.

While he was best known for popularizing the psychoactive ingredients in MDMA, Shulgin was something of a psychedelic Thomas Edison, inventing more than 200 drugs in a laboratory constructed in his backyard.

For the full story on Shulgin, check out Dirty Pictures, a 2010 documentary about his groundbreaking work, which is streaming in its entirety on YouTube:

If reading’s more your thing, here’s a quick rundown of what made Shulgin one of the most important and unique scientists in modern America.

Born in Berkeley, Calif., in 1925 to a pair of schoolteachers, Shulgin began his academic career briefly studying chemistry at Harvard before dropping out to join the Navy. After leaving the Navy, he returned to his hometown and earned a biochemistry doctorate at the University of California at Berkeley.

He took a job with Dow Chemical and created Zectran, the first biodegradable pesticide. Zectran was a massive success for Dow and, as a result, the company gave him significant leeway to research virtually whatever he wanted.

What Shulgin wanted to research was drugs. He was intrigued by mescaline—a hallucinogenic drug derived from the peyote cactus—and devoted the rest of his life to researching and creating new drugs that came with mind-expanding possibilities.

One of the early drugs he developed at at Dow was called DOM, a potent psychedelic amphetamine. An unaffiliated chemist named Nick Sand started cooking his own DOM in San Francisco, which he sold in massive quantities to the Hell’s Angels in the late 1960s. The drug swept the nation and caused a media frenzy. Eventually, it was publicly revealed that DOM originated inside the belly of one of the world’s premier chemical firms, and Dow severed ties with Shulgin.

“Chemistry is pornography in disguise,” Shulgin once said. ?You just have to know which functional group to look at.”

While Shulgin didn’t invent ecstasy—the chemical was created by Merck in 1921 as an attempt to develop a blood-clotting agent—he developed a new, simpler method for synthesizing the drug. After his breakthrough with MDMA, Shulgin, along with his wife and research partner Ann and psychologist Leo Zeff, led a campaign to persuade psychotherapists to use the drug as part of their therapy regimens.

Despite working on what some might consider the edge of legality, Shulgin never ran into much trouble from law enforcement. He had permission from the Drug Enforcement Agency to conduct his research and drug sampling events with colleagues. The agency eventually raided his lab in the mid-1990s, but Shulgin was never charged with a crime.

Shulgin escaped prosecution largely because most of the drugs he created didn’t exist outside of his laboratory, and government officials hadn’t yet had the opportunity to make them illegal.

Whereas other drug researchers would test new compounds on animals, Shulgin was insistent on using human test subjects—most commonly himself. The Guardian notes that Shulgin’s trial process involved hypothesizing what was the minimum possible dose a given new drug was required to have a effect and then take a tiny fraction of that amount, gradually upping the dose over time until he noticed something happening. He would then record the effects based on his own personal rating scale.

After testing on himself, Shulgin would frequently use his wife and friends as test subjects.

Shulgin’s insistence on using human test subjects is due to his belief in the importance of judging each drug’s potential psychological benefits for humanity—something that would be difficult to discern with animal testing.

“How long will this last, this delicious feeling of being alive, of having penetrated the veil which hides beauty and the wonders of celestial vistas?,” Shulgin wrote in his 1990 book Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story. ?It doesn’t matter, as there can be nothing but gratitude for even a glimpse of what exists for those who can become open to it.”

Photo by JonRHanna/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)