To the casual observer, the political machinations of Washington, D.C., can seem a world removed from the daily lives of ordinary Americans. When studies have shown that the only voices that really matter are the ones belonging to people with millions of dollars in their pockets, how does that average citizen get their elected representatives to hear them?

According to a report released on Wednesday by the nonprofit Congressional Management Foundation, the answer is surprising simple—tweet at them. They’re listening,

The report’s authors surveyed 116 communications and legislative staffers working for senators and members of the House of Representatives during a two-month period last year, with a breakdown slanted toward Democrats by about 10 points. The questions were about how the staffers used social media to interact with constituents. Overwhelmingly, the staffers asserted that not only were they using social media as an important tool in learning what their constituents cared about, but the number of Twitter or Facebook comments required to make them start paying attention to a given issue is surprisingly tiny.

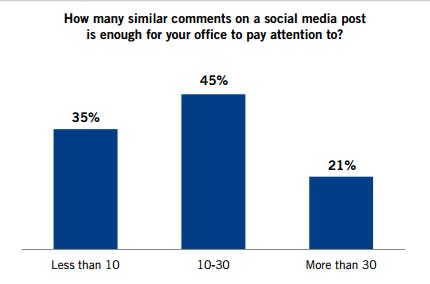

Eighty percent of respondents said it took fewer than 30 tweets or Facebook comments to make a staffer “pay attention” to an issue.

Congressional Management Foundation CEO and report co-author Bradford Fitch insisted that, while getting a congressperson’s office to simply pay attention to an issue resonating with voters may not seem like much, it’s an important first step in pushing a lawmaker to take a given position.

“Let’s say, the legislator tweets something and 30 people respond to it—either positively or negatively. The communications director would tell the lawmaker or someone close to them, ‘hey, look what people are saying about you,’” Fitch said. “It is literally a way for knowing that your voice is heard and that the data, in some loose and causal way, is integrated into the member’s thinking.”

Fitch added that the small number social-media messages necessary to pique a congressional office’s interest was interesting, especially when there are so many industry associations and politically minded nonprofits spending millions of dollars every year barraging congressional servers with emails. Messages sent via social media, on the other hand, seem to carry far more bang for their buck.

“Social media has a couple of qualities that email doesn’t have. First there is an authenticity about social media that frankly doesn’t often come through in form email campaigns. Said another way, you can’t fake a YouTube video,” Fitch noted. “There’s also an immediacy to it. The only other fast form of communications to Capitol Hill is, of course, a phone call. But when you do mass phone call campaigns, you can collect two data points: yes or no. You can’t collect the other data points. That’s where social media allows a much more robust communications tool than a form campaign.”

The report also looked into what factors increase the probability of a tweet or Facebook message resonating with a staffer. The first is timing. When a lawmaker posts about an issue, the likelihood staffers will review comments or replies drops precipitously with time. More than half will look at reactions six hours after the fact, but that number drops to 23 percent when the time frame is extended to a period of a week.

There’s also the issue of whether or not the commenter is a constituent of the lawmaker or not. Considerably more weight is given to responses sent by people who live in the legislator’s state or home district, and therefore ultimately control their electoral fate. The staffers surveyed say they often had difficulty determining if someone is a constituent.

The lesson here is that, if you want to get a lawmaker’s attention, reply to one of their Facebook posts or tweets about an issue you care about as soon as it goes up and let them know you’re a constituent.

While tweeting is a good way to get noticed, booking an actual face-to-face meeting with a lawmaker likely takes something slightly harder to come by than a Twitter account—money. Earlier this year, a pair of U.C. Berkeley political scientists tried to schedule meetings with members of Congress, alternately saying the meeting were with campaign donors versus regular constituents.

The lawmakers were 231 percent more likely to meet with people identified as donors.

Photo via Elliot P./Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)