For many fans of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show, disappointment at the news that Jon Stewart will soon be stepping down as host was overshadowed almost immediately by excitement at the idea that 25-year-old Jessica Williams, the show’s youngest-ever correspondent, might take over. A Change.org petition asking Comedy Central to hire her as host quickly gathered over 14,000 signatures.

Williams responded graciously, thanking her fans for their support but letting them know that she will not be hosting the program:

https://twitter.com/msjwilly/status/567145287916204032

https://twitter.com/msjwilly/status/567145544699904000

https://twitter.com/msjwilly/status/567146007725887488

At that point, everyone collectively said “Aw, too bad, can’t wait to see more of your work!” and left Williams alone.

I’m joking, obviously. That’s not what happened, because if there’s anything we love to do in our society, it’s telling women—especially women of color—what to do. Bonus points if we demand that they perform for us the way we want them to.

Instead, Ester Bloom wrote a piece for the Billfold in which she armchair-diagnosed Williams with “impostor syndrome,” what Bloom describes as “a well-documented phenomenon in which men look at their abilities vs the requirements of a job posting and round up, whereas women do the same and round down, calling themselves ‘unqualified.'” Bloom argued that Williams was displaying “clear symptoms” of the syndrome and that she should get to “the best Lean In group of all time.”

Williams responded on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/msjwilly/status/567790586045140992

https://twitter.com/msjwilly/status/567796911995121664

To her credit, Bloom then apologized, adding to her post:

I wanted to state officially and for the record, as I have on Twitter, that I was wrong. I was offensive and presumptuous; I messed up, and I’m sorry. Williams should not have had to deal with this shit: my calling her a “victim” of anything, my acting like I know better and could diagnose her with anything, all of it.

So what happened here? How did Bloom go so self-admittedly wrong?

I understand that it can be unpleasant to watch a talented woman turning down a role that she claims she’s unqualified for. For feminists of the Lean In variety (i.e., feminists who believe that the problem of female underrepresentation can be solved by women deciding to take on these roles), it makes sense that Williams’ brief explanation might read as “clear symptoms” of impostor syndrome. As the saying goes, if you only have a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.

“Leaning in” is just one tool in the toolbox of fighting sexism. It can be useful in some cases, and for certain categories of women. (They tend to be the ones who look like Sheryl Sandberg, if you’re wondering.) And just like a hammer, “leaning in” is a blunt instrument—it doesn’t get at the nuances of how sexism functions in our society and how it intersects with other oppressive systems, like racism and classism.

At Feministing, Maya Dusenbery writes:

This is exactly the problem with “lean in” feminism: It puts the burden on individual women—even, in this case, pressuring them to do things they don’t actually want to do—to change a status quo that, in reality, is upheld by systemic inequalities that all the “leaning in” in the world can’t fix on their own.

Bloom’s piece implicitly blames Williams for not doing more to advance the cause of women of color in comedy. But first of all, Williams is doing much more for that cause than most people—certainly more than any white woman—simply by doing what she’s already doing. Second, it’s not her responsibility to singlehandedly fix racism and sexism in comedy. If white women want to address this issue—and I believe we should—it’s on us to elevate the voices of women of color and support them in their work. And supporting them requires respecting their boundaries when they say they don’t want to do something.

But in any case, I’m not so sure that Williams has a problem with impostor syndrome—and if she does, that’s between her and her therapist or professional mentor and is absolutely none of my business. More likely, she knows what’s at stake and has decided it’s not for her. As Mikki Kendall noted on Twitter, there are few people more qualified than Williams to make that call:

https://twitter.com/Karnythia/status/568072044778299392

https://twitter.com/Karnythia/status/568072207093665792

Williams doesn’t owe anyone an explanation as to why she doesn’t want to host The Daily Show, but her tweets suggested a possible reason: She might not feel like she can handle constantly trying to turn awful political events into humor. As she tweeted, “if something happens politically that I don’t agree with, I need to go to my room & like not come out for, like, 7 days.”

It’s a demanding job, more so than any of us can really imagine. It’s also worth noting that, while it’s tempting to assume that Williams is qualified because she’s clearly talented and well-liked, Jon Stewart was 37 years old when he started The Daily Show. Taking over an already-popular and beloved show and keeping it that way also adds some extra challenges. Her assessment of her qualifications may actually be right on-point, and maybe in a few years we’ll see Williams running her own Comedy Central show.

Tying this story in with numerous other conversations about black women in the media, Mikki Kendall further wrote:

Now, the obligatory apologies are already happening, and Jessica Williams has made it very clear that she is no one’s project, poster child, or puppet. That’s all wonderful. But what happens the next time a black woman in the public eye makes a decision that maybe doesn’t work for mainstream white feminist narratives? We’ve seen this with Beyoncé, Nicki Minaj, Viola Davis, and so many others. And whether it’s an insistence that black women not show their bodies as performers in order to be considered “good feminists” (while white women are lauded for owning their sexuality, á la Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry, etc.), or that they not discuss white-centered beauty aesthetics and their impact on hiring in Hollywood, we run again and again into the same problem: No matter how black women or other WOC conduct themselves, somehow their very complicated lives and choices are reduced to single-note racist tropes.

It’s time for white women (and everyone else, really) to stop telling black women what to do. It’s also time to acknowledge that repeatedly telling someone to do something they’ve said they don’t want to do is not a “compliment,” “support” or “doing them a favor.” It’s patronizing and rude.

I hope that Jessica Williams’ fans will continue to support her work, whether or not it’s what they personally wanted her to choose.

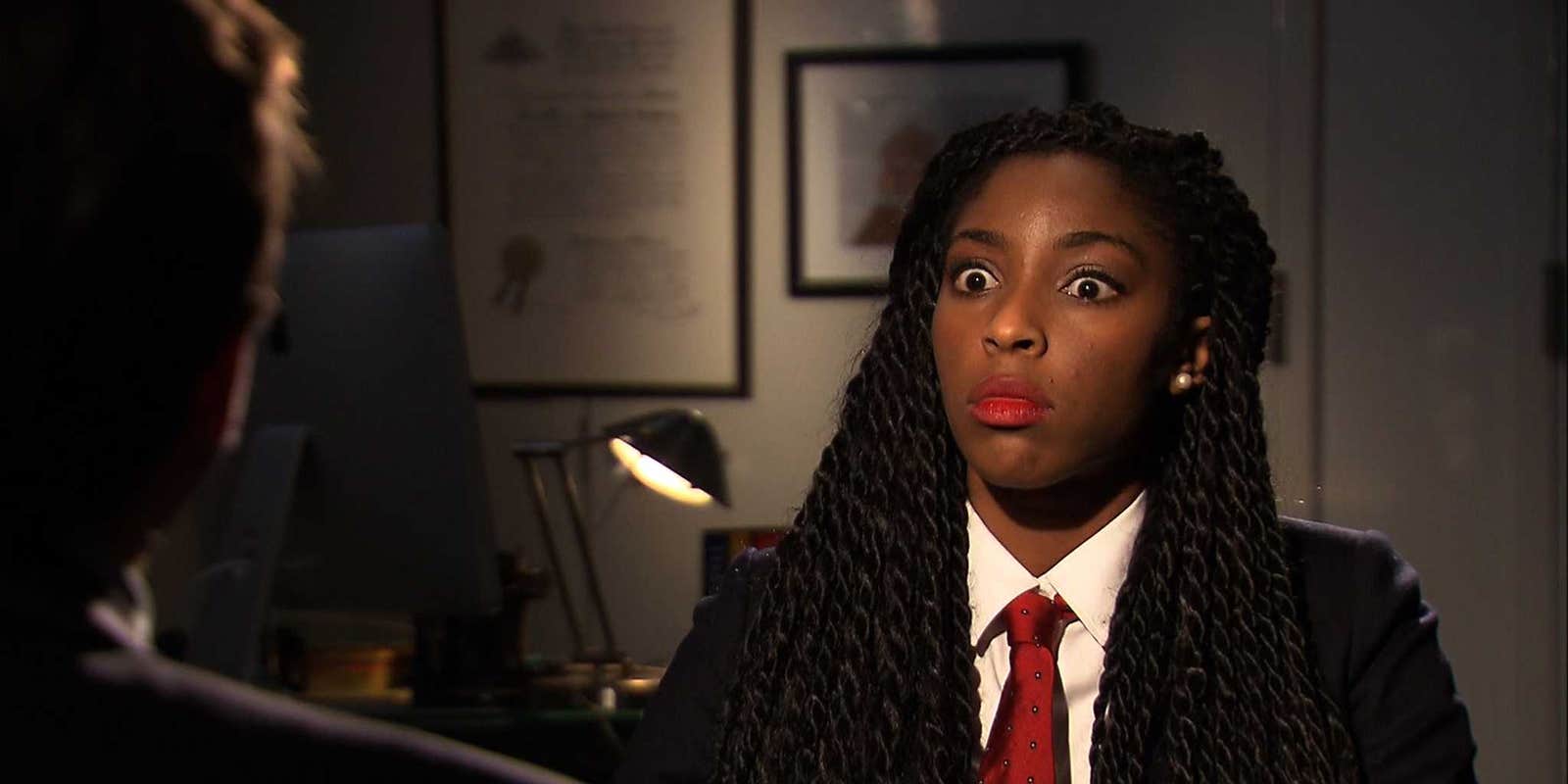

Photo via Comedy Central/YouTube