Say you’re paging through a message board and come across a photo, only something about it seems off. The way it’s framed, you get the sense you’re meant to see something that’s barely visible. That’s when the figure emerges—a tall and spindly form, nearly humanoid save for his ghastly proportions. He’s so slight, so indistinct, you have to convince yourself he’s not a trick of the eye. Nevertheless, there he is, seared into your mind for good.

You’ve just met the Slender Man, and life will never be the same.

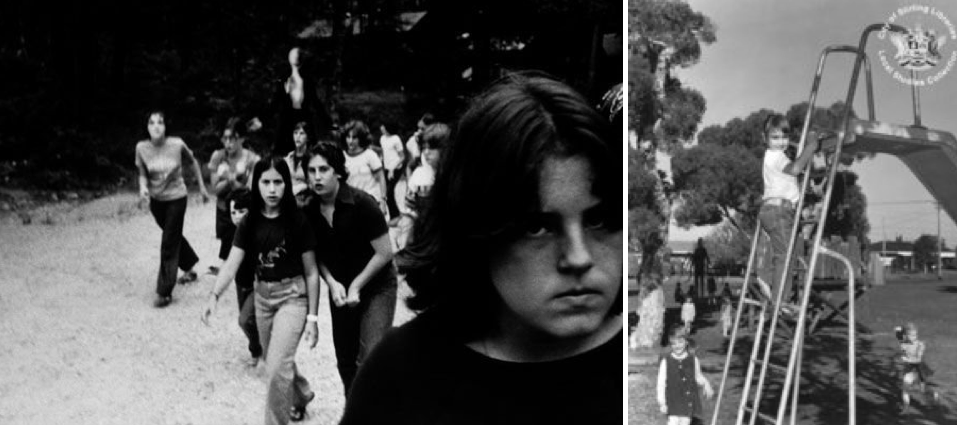

Timeless though he seems, the Slender Man is really quite young. He first appeared on June 10, 2009, in a thread on legendary Web community Something Awful that invited members to create their own “paranormal images.” One user, who went by the handle Victor Surge and whose real name is Eric Knudsen, contributed an elegantly creepy Photoshopped image. It had just the right details to convince a gullible or easily scared reader of its veracity: Just two ambiguously unsettling images with a small postscript.

“[R]ecovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen children vanished and for what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man.’ Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence. 1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.”

Other posters at Something Awful liked the idea and ran with it, and Knudsen himself added further macabre details of the supposed library incident. Within weeks, Slender Man was a bona-fide paranormal meme, picked up by online communities including 4chan and DeviantART.

These Internet denizens ascribed various eerie powers to the Slender Man, including mind control and forced memory loss, along with physical features like tentacles and an eyeless face. He was no longer just a lean abductor of children. He was now the stuff of hundreds of competing nightmares, going by many other aliases: Tall Man, Mr. Slim, Der Großmann, and, most insidiously, the Operator.

It’s in this last guise that he’ll make his big-screen debut. Next year, at long last, the Slender Man (or at least one version of him) may leap from inside joke to blockbuster monster.

That’s the thinking on Marble Hornets, an adaptation of a creepy webseries of the same name from filmmakers Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage. If everything goes as planned, they will have succeeded where others have failed: moving Slender Man from viral phenomenon to mainstream icon. Because lurking on the fringes of Internet culture is an anonymous rights holder who has swatted down every other attempt to profit from the meme, attracting an air of impenetrable menace, not unlike Slender Man himself.

…

In a 2011 interview on fan site slenderman235, Knudsen spoke about the surprising, sweeping success of his one-off gag:

I didn’t expect it to move beyon[d] the SA forums. And when it did, I found it interesting to watch as sort of an accelerated version of an urban legend. It differs from the prior concept of the urban legend in that it is on the Internet, and this both helps and harms the status of the Slender Man as one. In my personal opinion, an urban legend requires an audience ignorant of the origin of the legend. It needs unverifiable third and fourth hand (or more) accounts to perpetuate the myth. On the Internet, anyone is privy to its origins as evidenced by the very public Something Awful thread. But what is funny is that despite this, it still spread.

Indeed, as Internet denizens endeavored to manufacture more proof of the Slender Man’s existence with YouTube clips, indie video games, purported sightings and fanart, the more he came to seem an inevitable—and chilling—force of nature. The fact that he’s a hodgepodge of often contradictory ideas only hints of an unnatural changeability, a characteristic that has everything to do with the volatile dynamics of the Internet that created him.

In an email to the Daily Dot, Troy Wagner, co-creator of Marble Hornets, spoke about how the Slender Man inspired their indie production:

I followed the [Something Awful] thread pretty closely and really liked where it was going after Victor Surge’s post. I wanted to get involved with it somehow, and noticed that no one had attempted anything related to video yet. I was going to school for film at the time, so I figured I could break into it that way. … We were able to use [Slender Man] as a starting point to make something original, which is what became The Operator in Marble Hornets.

If we understand horror films, as most academics do, to be expressions of our lasting and often repressed fears as a society—from a terror of the unknown (Alien, Jaws) to media saturation (the Scream franchise) to political angst (the torture porn fad) and addiction, familial trauma, and genocide (The Shining)—then Slender Man can be viewed as a manifestation of what scares us most in the digital age. In his presentation as a pseudo-realistic, heavily documented figure, he underscores how unreliable online information is, how detached we’ve become from reality, and how much the Internet and the tangible world have begun to overlap.

It was just a matter of time, then, before film adaptations came knocking: After all, if the entire Internet were gathered around a bonfire in the woods at midnight, this is the ghost story they would want to hear. A flexible premise, with a striking villain at the center, and a built-in, heavily engaged fanbase? At least from a marketing perspective, what’s not to love?

…

Hollywood was initially beat to the punch by filmmaker A.J. Meadows, who in 2012 launched a Kickstarter for an indie film, The Slender Man. In it, he aimed to tell the story of a “tall, thin, human-like creature (appearing to wear a suit) who snatches up children and in some cases adults as well.

The Slender Man watches and stalks its prey before consuming it. It’s said that the more you believe in the Slender Man, the easier it is for him to get you. Some versions of the myth state that the Slender Man can only be seen on video or photographs.”

In an interview with MovieTimes.com, Meadows spoke about the prickly nature of his online audience, revealing an understandable naïveté over what was to come:

Well, we understand that the Slender Man fans are very protective of the source material they’ve created and consumed over the years, so we want to make sure that we provide them with a film they can enjoy and perhaps even be proud of. My team and I are big fans of the mythos ourselves and want to pay tribute to all of the Slender Man creators and media they’ve created that has inspired us (and given us nightmares… for years).

Meadows’s modest $10,000 budget was more than met by deadline, and he went on to make the film, but good luck finding it these days. Both the website hosting the finished product and every subsequent YouTube upload have been taken down over copyright complaints since its February 2013 release.

A 12-minute film written and directed by Braeden Orr, also titled The Slender Man, came out in 2012: “Five college students go out into the nearby woods to have one last fling before graduation. Plans change when they start to find strange notes and are stalked by a mysterious faceless man.”

That YouTube video was set to private, and then it, too, became simply “unavailable.” Which raises an interesting question: Who claimed this seemingly organic meme was their exclusive intellectual property?

Don’t look at Eric Knudsen—he’s given his blessing to plenty of Slender Man products that have gone on to face legal challenges. Take, for example, Faceless, a multiplayer horror survival video game that originally went by the title Slender: Source.

A few months after Meadows’s film was wiped from the Internet, the popular Knudsen-approved Faceless was blocked on Steam Greenlight, an experimental crowdsourcing service for games, developed by Valve Corp.. It turned out that Valve itself had blocked it, after sensing potential copyright disaster. It’s since allowed the game to return.

It turns out that although Knudsen is the undisputed creator of Slender Man, there’s a third-party option holder with the right to determine his appearance in film, TV, video games and other for-profit entertainment.

The option holder’s identity remains a puzzle—the closest thing to a commercial precursor for the Slender Man is a faceless phantom referred to as “Tall Man,” who first appeared in Trilby’s Notes, one of a series of adventure games by Ben Croshaw. It seems unlikely, however, that Cronshaw has anything to do with the copyright battles, considering the depth that separates his character from the Slender Man.

Even Wagner, one of the Marble Hornets creators, was reluctant to touch on the strange copyright conditions:

I’m not sure how much I’m able to say on the subject, really. There have been a few challenges in regards to [the Marble Hornets film], but nothing significant enough to impede anything for us. I’ve heard a few things about the “mysterious option holder,” but just to be on the safe side I can’t really share specifics.

…

Marble Hornets, by far the most successful video offshoot of the Slender Man phenomenon, may be just different enough from other permutations of the legend to render the copyright issue moot.

In fact, the “Slender Man” is not once mentioned; the villain of the series is the Operator, who slowly drives a young film student named Alex insane in a series of tapes kept and later combed and catalogued by Jay, a friend who is then sucked into the same hidden world of paranoia, violence, and destruction. The tapes’ visuals and audio tracks are routinely abraded, as if the proximity of the Operator—who only appears in brief flashes, or positioned at a distance, barely noticeable at first—causes human technology to malfunction.

The original series boasts about 325,000 subscribers and more than 65 million views across 74 “entries” posted over the last four years. That success helped it get picked up in February by the film studio Mosaic, better known for R-rated comedies like The Other Guys and Bad Teacher. Screenwriter Ian Shorr will adapt the concept from series creators Wagner and DeLage. Paranormal Activity veteran James Moran will direct, and the film is slated for a 2014 release.

Wagner explained the character’s impact further:

“I see The Operator as a kind of monster that fits into our technologically minded day and age. Looking at it from a real world’s perspective, it’s a being whose existence couldn’t be proven until video cameras were around, and couldn’t be easily shown until the Internet age.”

Wagner continued: “At the same time, we see cameras and similar technology as some kind of great neutral. They don’t have biases or opinions or ulterior motives, they just capture whatever is in front of them. So keeping that in mind, we wanted to take that way of thinking and kind of turn it on its head. What if the camera captured something you swore wasn’t there? Something that’s very presence caused the camera to glitch and become unreliable, almost like it itself is hallucinating. But YOUR memory of the event also seems to have been mysteriously affected. What then do you trust? Your own faulty memory or the unflinching lens of the camera? That’s the approach we try to take to the classic fear of the unknown.”

As a horror film about filmmaking, the original Marble Hornets owes something to The Blair Witch Project and Wes Craven. It’s often deliberately dull, if tense—the “found footage” does include distorted moments of terror-stricken panic and suspense, but you may wait 10 full minutes to get jolted out of your seat. Like Twin Peaks, it doesn’t seek to answer the original questions so much as unravel its characters and instill an all-pervasive mood of some deeply felt unknown. The clips themselves are meant to be non-chronological, but their sequence creates another layer of narrative, a neat effect for a series that’s about following someone else down a dark rabbit hole: Jay follows in Alex’s footsteps, and we follow in Jay’s.

This type of immersion is at the heart of the Slender Man concept. Once you know about him, he will take over your life, rather like the Internet forums he stalks. The Web is saturated with his legend: photos, fiction, paintings and films hitting all the valences of one archetypal character.

As tales of vampires and werewolves frightened a generation still transitioning from folklore and age-old superstition to an age of scientific enlightenment, Slender Man haunts the fringes of a radical technology that humankind has only just begun to absorb, but his message is quite clear: One wrong turn is all it takes to see something you’ll wish you hadn’t.

Photo via mdl70/Flickr