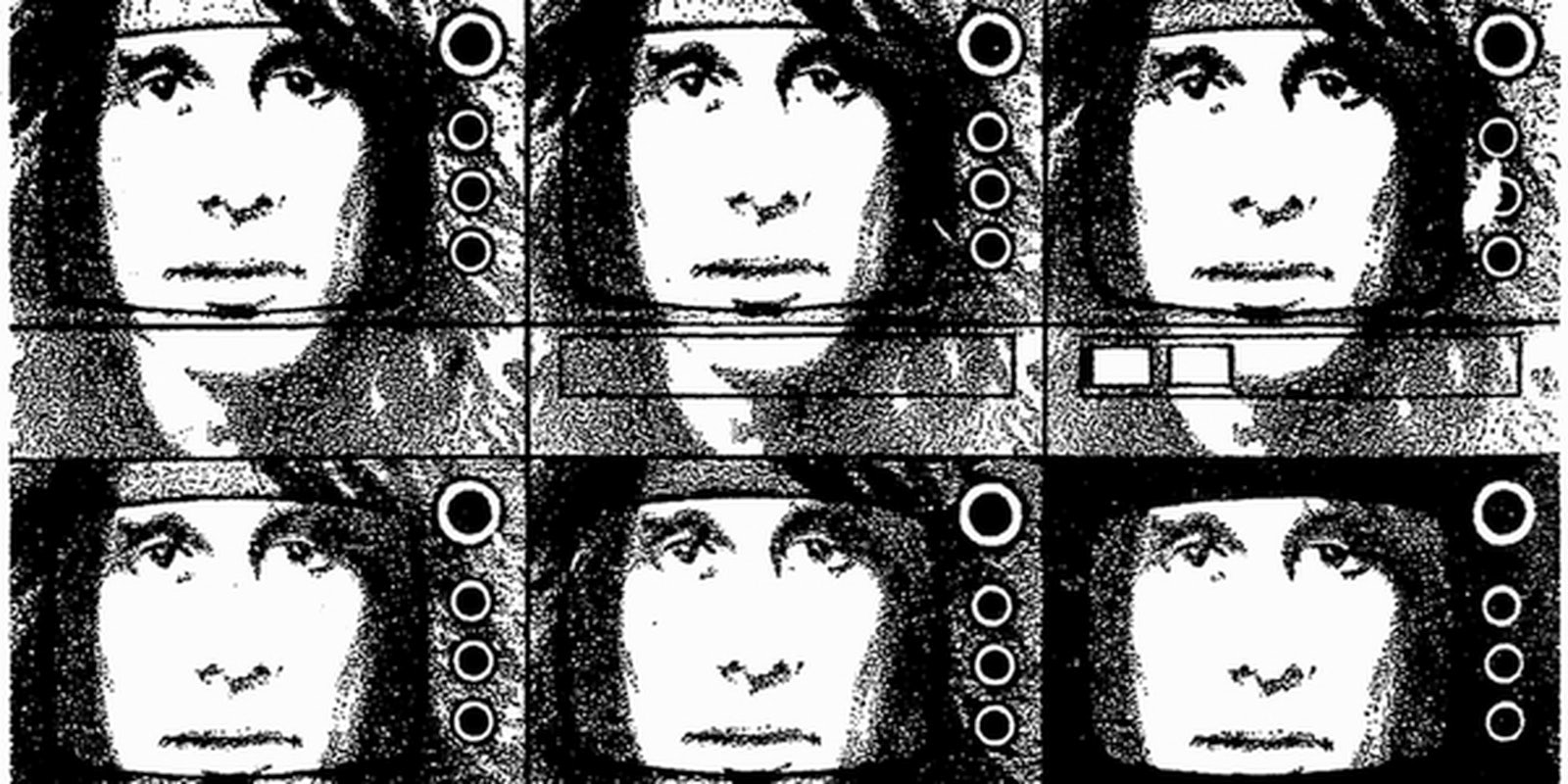

I fell stupidly and hopelessly in love with Todd Rundgren in the span of two days, thanks to the Internet.

My initial encounter with the artist was analog. One weekend, after hearing Alex Chilton play a Todd Rundgren song at the Brooklyn Masonic Temple, I found an old Todd record on a bottom shelf at the used record store on 72nd Street, just off Broadway. But the real bite was entirely digital. After listening to both sides of the album multiple times, intrigued, I wanted more, and decided to look him up on YouTube. Within seconds, I found the channel of a user who had uploaded clips from various highlights in Todd’s career, and clicked on a video from a live show Todd did in Columbus, Ohio, in 1980. The video’s no longer online, but I can remember it perfectly. There he was, buck-toothed Todd, hair blowing in the wind, sporting a white suit and an acoustic guitar. “Who is this guy?” I thought. I was mesmerized. And I started to listen. And hit replay. Then I pressed play on the next video, then the next, then the next after that.

Within the course of a single weekend, I’d made my way through his entire back catalogue. I’d found old self-made promo clips of psychedelic visual effects promoting Hermit of Mink Hollow. I’d found an interview he did with Patti Smith, then a review Patti Smith wrote of his album, then the album of Patti Smith’s that Todd produced. I’d found photos of him and Bebe Buell riding a tractor, photos of him in a tiger print shirt standing over a mixing desk. I found interviews from tours in Japan, interviews from last year. I joined Todd in his decades-long journey around the world, the fans who had spent as long trailing in his footsteps. I read their stories on forums. I fed off their excitement.

I’d found everything he’d ever done. A 50-year career consumed, for the most part, in less than three days; after a single weekend spent largely in seclusion with headphones buried in my ears, I emerged, with the glazed eyes of a cave fish, as the biggest Todd Rundgren fan in the world.

I can almost remember what this was like before the Internet, before the widespread availability of streaming videos, back catalogs downloadable at a keystroke, before photographs were indexed and searchable from the comfort of your home. It happened like this: You would hear a song on the radio, save your allowance, and stalk the record store for the copy of the album that contained that song. Sometimes you might have to wait for your birthday. At its worst, impatience manifested itself in a young you sitting by the tape deck with your fingers hovered over RECORD and PLAY, waiting to capture the song on cassette. I once paid my sister to sit there for me and record my request when I had to leave my post for a few hours because I just had to have the song I’d heard in a scene of Joe Versus the Volcano.

The build was slow; it happened over years. Now? Now we devote weekends to infatuation. Less than that. Minutes. I love everything you’ve ever done, and I know that, immediately, because the Internet contains everything you’ve ever done.

We gorge not just on music videos but on television shows: the restless devouring of season upon season of The Wire, marathon sessions rather than the slow, drawn-out way we once consumed things—waiting a week for your show to air.

I wonder, though: As quickly as we’re able to fall in love, so fully and completely, do we grow restless once we’ve already seen it all? The vast catalog of materials related to a single topic can be scaled, consumed, and discarded in a single day. We binge and purge great barrels of information and art and knowledge. Our disposable culture applies to the digital world as well: We consume voraciously, then discard the bones as soon as we’re able to swallow. A topic, once Googled, can consume your entire day—a wormhole so great it swallows up the hours. But just as quickly as it began, we’re on to the next thing.

Some people will still visit record fairs far and wide searching for a particular pressing of a particular album by a particular artist to complete their collection. It’s the search that matters, the thrill of finding something they’ve been looking for for years. The hunt for old records is undeniably delicious. So what does that mean now when I can type three words into a search engine and find a Japanese pressing of an album on eBay? What does the search matter, if within seconds you can hear the most obscure song you’ve ever known streaming through your headphones?

The idea of anything being “unknown” or “obscure” is itself becoming more unknown and obscure. Everything is public knowledge, existing on the surface. In order to claim obscurity, we’re reaching deep into the musical back catalogues of foreign countries to find something that no one else has ever heard before. We’re digging deeper and faster until no stone is unturned.

We keep searching because we are insatiable creatures. Our own dissatisfaction, though, is entirely our fault. We complain that a series didn’t last long enough, when it’s our own speed of consumption that makes it seem like a shorter love affair. We could stretch things out; we could pace ourselves. But no, because we can consume everything all at once, that’s exactly what many of us tend to do.

(Our inability to control our consumption when so much is available was parodied most awesomely in the Portlandia sketch where Fred and Carrie decide to watch just one episode of Battlestar Galactica, then another, then another, before they end up losing their jobs, their electricity, and in the end, forcing the cast to create more episodes rather than suffer through the horror of their binge coming to an end.)

We obsess and collect because we can. It’s too easy not to. But when we come up for air, and we see ourselves lying there on the carpet, drunk on consumption, the discarded bones of every Fleetwood Mac outtake we could find in the span of an hour scattered at our feet, where does that leave us? What is left to discover? What is left to fall in love with?

Are we in love, or are we just addicts, consuming without thinking about what it is we’re consuming, what we’re watching, or hearing, or obsessing over?

If the limitlessness of the Internet enables our addictions, will its speed ultimately cure us when we realize we’ve seen it all?

Hurry up. I can’t wait. I love everything you’ve ever done.

Zan McQuade is a writer, editor, photographer, translator, and baseball enthusiast living in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her words and images can be found at www.thatcupoftea.com.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons