What do a 5-year-old Canadian named Eli Dirr, a Kansas highschooler named Kaycee Nicole, and a Colorado firefighter named Jesse Jubilee James all have in common?

For starters, none of them ever existed outside of the Internet.

Even more bizarrely, they all faked their deaths via life-threatening illnesses, in some cases garnering support from hundreds, even thousands of friends.

You’ve heard the horror stories before: perhaps in the film Catfish—an Internet story about Internet fakers that might be faking itself—where a housewife named Angela Wesselman fabricates the existence of a cancer-ridden daughter, along with dozens of fictional friends.

What you may not know is that these stories make up a clinical diagnosis called Munchausen by Internet—the act of fabricating disorders, your own or other people’s, via the attention-nabbing stage of the Internet.

Munchausen by Internet is the virtual re-enactment of Munchausen’s Syndrome, wherein a person constructs an illness or series of illnesses requiring repeated trips to the hospital and repeated attention from others. Related is Munchausen by Proxy, in which those suffering from the disorder inflict abuse upon children or other victims so that they themselves will receive attention and sympathy.

There’s no clinical term for Munchausen By Proxy By Internet—that is, the act of creating a fictional character and then giving them illnesses, rather than doing it yourself. The pattern, however, seems to be consistent whether you’re the DIY type or the sockpuppet type: Step One: meet other people on the internet; Step Two: convince them that you (or your fictional stand-in) are suffering from a heartbreaking disease; Step Three: profit from their attention and more.

Typically, when the lie becomes too heavy to maintain, the creator of the illness will simply stage the death their fictional character. Such was the case for Eli, Kaycee, and Jesse, all three of whom were created by women from the Midwestern U.S., and all three of whom eventually “died” of cancer.

The LiveJournal community Fake LJ Deaths has investigated and confirmed dozens of faked deaths and serious illnesses on the journaling site. Howard Swains, writing in Wired, claimed, “In two investigations between 2007 and 2009, I encountered countless examples of fake deaths in all corners of the online world.”

There’s even an Instruction Guide. “Faking your own death is a time-honored tradition,” explains Luke Lewis in his satirical YouTube video.

Often Munchausen by Internet is about getting attention or manipulating virtual friends of the user. Unfortunately, the perpetuators of the hoax often morph into scammers and defrauders as well, asking their victims for gifts, money, and emotional support. The victim of the Jesse James identity scam wound up suing the perpetrator for, among other things, $10,000 in gifts paid out to the alleged Jesse, with whom she had been having a relationship.

The latest case of Munchausen by Internet is a teenager named Jadzia Richlin who was outed for faking cancer and then requesting gifts from cancer charities and other organizations. Before that, it was Brett Schmidt, who claimed to be suffering from three different types of cancer while running a fundraising campaign called “Fighting for Schmidty.”

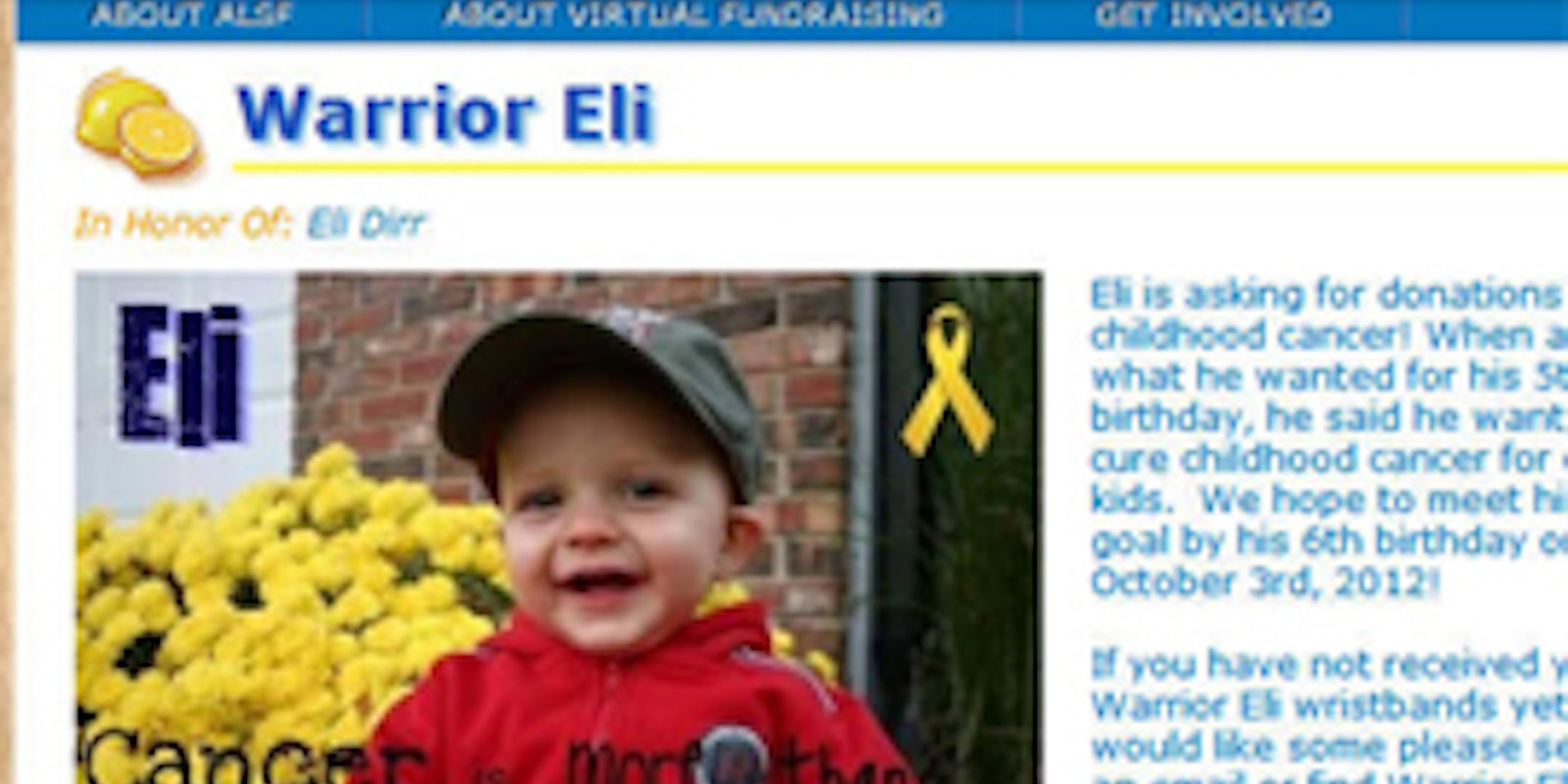

Both of these cases were debunked within the past month by the blog Warrior Eli: A Hoax?. Taryn Wright began the blog in May to document the demise of the Eli Dirr scam, which involved an entire family of fake online identities. The Eli hoax scammed hundreds of people out of thousands of dollars over a 10-year period. Beginning with evidence of stolen Facebook photos, Wright and other investigators were able to undo in just a few hours what one woman, a 22-year-old named Emily Dirr, had built up over a decade.

Dirr may have taken lessons from Lewis’ satirical YouTube instruction manual for death-faking: She offed one of her fake family members via a car crash, and another via terminal illness—the two main ways Lewis suggests to fake your Internet death believably and efficiently.

But, as Dirr, Richlin, and each of the other perpetrators learned the hard way, Internet culture is growing savvier all the time. People are learning to question stories that seem too tragic to be true. As privacy concerns grow, and the ease of fabricating whole new identities and medical records dwindles, the possibilities of successfully carrying off Munchausen by Internet grow smaller with every new hoax.

Photo via Warrior Eli: A Hoax