If you’re reading this right now, you’re likely helping someone else make money.

In the digital age, everything you do online is creating data—and that data has become a powerful commodity. Companies like Facebook and Google make billions of dollars every year collecting information about our online habits and using that data to tailor ads.

One man has had enough. Federico Zannier of Brooklyn, N.Y., is tired of seeing his data harvested and sold off to the highest bidder by someone else. So several months ago he an idea: He’d harvest and sell his own data.

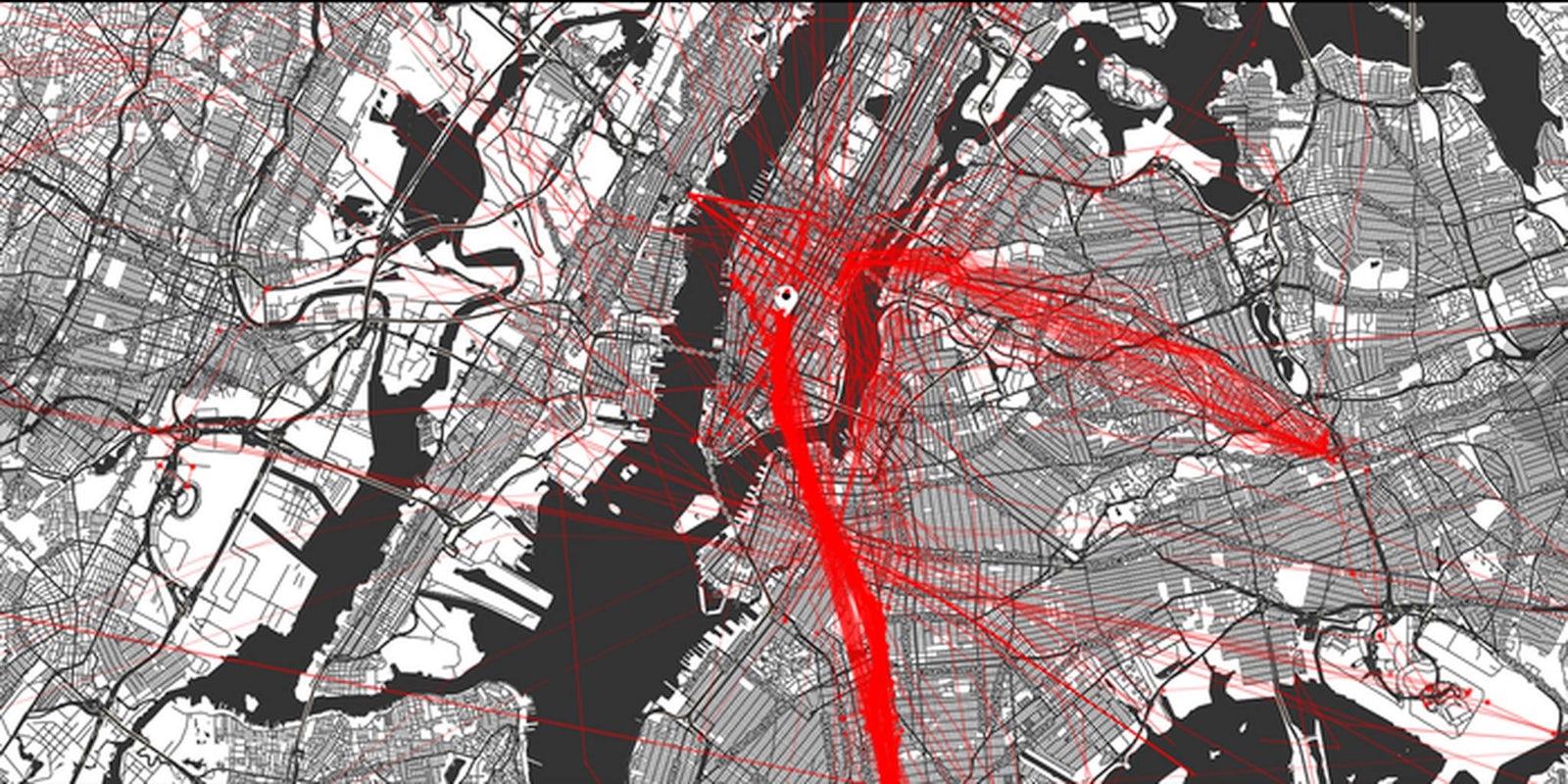

For several months now, Zannier has been personally tracking and storing info about all his online activities, including GPS information, app usage, websites history, even mouse position. And last month, he decided to put it all up for sale on Kickstarter. For $2 a day, anyone can buy all this data about Zannier.

“In 2012, advertising revenue in the United States was around $30 billion,” Zannier says on the campaign page. “That same year, I made exactly $0 from my own data. But what if I tracked everything myself? Could I at least make a couple bucks back?”

It turns out he can. So far, Zannier has made $192 selling his data to 22 backers. Most have chipped in $2 to receive one day’s worth of data, which includes a list of the 70 odd websites he regularly visits, 500 screenshots, 500 webcam images, a recording of all his cursor movements, his GPS location, and app log. Bigger donations buy more data and an app that would allow users to similarly track their information.

It’s Zannier’s hope that other Internet users will begin to follow his example as a way of protesting the current market model. He says marketers should pay users directly for their data, rather than allowing middlemen to collect all the profits.

“Corporations have been using my data for their own profit,” Zannier says. “They use and sell my data. Often we don’t understand that by signing the terms of service we give away the rights to all our own data.”

But he’s not the only one irked by this business model. Last year, representatives from some of the nation’s leading data-mining companies were called before Congress to testify about their companies’ business practices. Companies like Epsilon and Intelius defended themselves, arguing that their business is perfectly legal as it merely aggregates and organizes publically available information. And many supporters argue that it’s ultimately good for consumers.

“I don’t think there’s anything scary about it,” personal finance reporter Erica Sandberg told Mashable. “Why wouldn’t they look at it? It’s public.”

But the Congressional committee investigating these matters didn’t see it the same way, vowing to “push for whatever steps are necessary to make sure Americans know how this industry operates and are granted control over their own information.”

Concern over data collection is not just a U.S. issue. France is currently considering a tax on companies like companies that practice data mining. The French are taking particular aim at Google, which makes an estimated $2 billion in advertising revenue in that country alone last year.

But while domestic and international lawmakers tackle this issue head-on, Zannier and others are trying to raise awareness through elaborate publicity stunts and protests. Earlier this year, a German performance artists, Johannes P. Osterhoff, began publicly displaying information about every book he read on his Kindle and emailing it directly to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Osterhoff said his goal was to devalue the data on which so many others are turning a profit.

“To make the data I generate public, is to devalue it,” Osterhoff told the Daily Dot. “This is why I prefer to share data in an open format.”

Photo by Federico Zannier/Kickstarter