Last week, Sarah Slocum, a San Francisco-based tech writer, wore Google Glass to a bar and was cursed out and assaulted by two women who ripped the Glass off her face. In a Facebook post responding to the attack, Slocum called it a “hate crime,” but the media response has ranged from hostile to dismissive. Newser’s Matt Cantor referred to Slocum as a “Glasshole” and New York magazine‘s Adam Martin called her argument an “overly fraught discussion of some idiocy that happened on the kind of drunken night you would usually want to forget.”

However, this rhetoric completely ignores the social context of Slocum’s attack, and I can understand why people like Slocum feel tempted to call incidents like this “hate crimes.” First of all, choosing to wear Google Glass can very much feel like an identity, especially to someone who otherwise doesn’t feel that they have much of a racial, cultural, or sexual identity. It’s a way to feel like you have an in-group, a way to signal certain interests and status—and with a $1,500 price tag, it certainly says something about your place in life. Being attacked because you’re wearing Google Glass can, thus, feel like an assault on your very identity, and the term “hate crime” seems to mean, to many people, something like “they committed a crime against me because of who I am as a person.”

But beyond that, calling something a “hate crime” adds a certain tone of immediacy and violation to it. I’m not surprised people often call things hate crimes when they’re not. Being mugged or even assaulted isn’t that uncommon, but being a victim of a hate crime is very uncommon—especially if you’re an affluent straight white person. Our criminal justice system is centered on perpetrators, not victims. There is no justice system to help victims of crimes restore a sense of safety and bodily autonomy. We have an institution to punish criminals, but not to support victims. Maybe referring to one’s experience as a hate crime is a way to garner sympathy that may otherwise be difficult to come by.

But “hate crime” does not mean “the perpetrator hates who I am as a person.” It doesn’t mean “this felt especially bad.” It means that the crime was committed with the intent of harming a person who is a member of a social group that has historically been subject to stigma, prejudice, and discrimination—not just on the interpersonal level (as occurs when, say, a white person dislikes a black person), but on the institutional level (as occurs when, say, black people are more likely to be arrested and convicted of crimes that are more likely to be committed by white people). The reason “hate crime” is an important category of crime to define and track this way is because it’s important to understand the effects of institutional oppression, especially since promoting hate against these groups encourages further attacks against them.

Do Google Glass wearers, or technology enthusiasts more broadly, fit into this category of groups? The answer is clearly no. They have not historically been denied rights according to other people. They do not suffer from poverty, sexual assault, violence, abuse, or unemployment at significantly higher rates than other people. They are not generally considered unfit to be friends, partners, parents, employees, or tenants. They are not targeted by the police for unjust stops and searches, and they are not given harsher sentences for committing the same crimes as other people. While people labeled “nerds” or “geeks” sometimes face ridicule or bullying, so do people who have red hair or whose last names sound funny.

While the assault Slocum experienced was probably not a hate crime, that doesn’t mean that there’s no social context to it. Her attackers seemed angry because they saw her as a member of the Bay Area’s tech elite, which many in the area see as taking over the city and driving out those who can’t afford the rising prices. Obviously—and I hope this doesn’t even need to be said—that’s not a reason to assault someone. But it’s a way to explain what might motivate someone to commit a crime like this without trying to compare it to a hate crime.

That said, not all the social media responses that disagree with Slocum’s framing of the situation have been helpful, either. On her Facebook post, you can see the typical “Well what did you think was gonna happen when you went out wearing _______” response, which is familiar to anyone who’s dealt with sexual assault. To be clear: No matter how douchey you think Google Glass is, that’s not a justification for attacking someone who’s wearing it.

Some commenters opined that perhaps Slocum’s attackers were concerned that she was violating their rights by videotaping them with the Glass. OK, sure.

But that’s also a concern whenever someone is holding up a camera or a cellphone. Attacking someone who’s doing that is not justifiable. There are plenty of other courses of action that can be taken in that situation, such as getting out of the person’s view, asking them if they’re recording you and asking them to stop, or alerting a bartender or bouncer. Slocum was apparently asked to remove the Glass and did not do so, but 1) that still doesn’t mean you get to play vigilante and rip it off her face and 2) it’s a bar—who knows if she even heard you?

In an ideal world, there would be room both for sympathy for Slocum for the assault she endured and for constructive criticism of her claim that it was a “hate crime.” Her misunderstanding of sociology—and, perhaps, of tech-related etiquette—does not make her experience any less harrowing.

Miri Mogilevsky is a social work student who loves feminism, politics, New York City, and asking people about their feelings. She has a B.A. in psychology but will not let that stop her from getting a job someday. She writes a blog called Brute Reason, tweets @sondosia, and rants on Tumblr. If you would like to be Miri’s best friend, send her cool psychology studies.

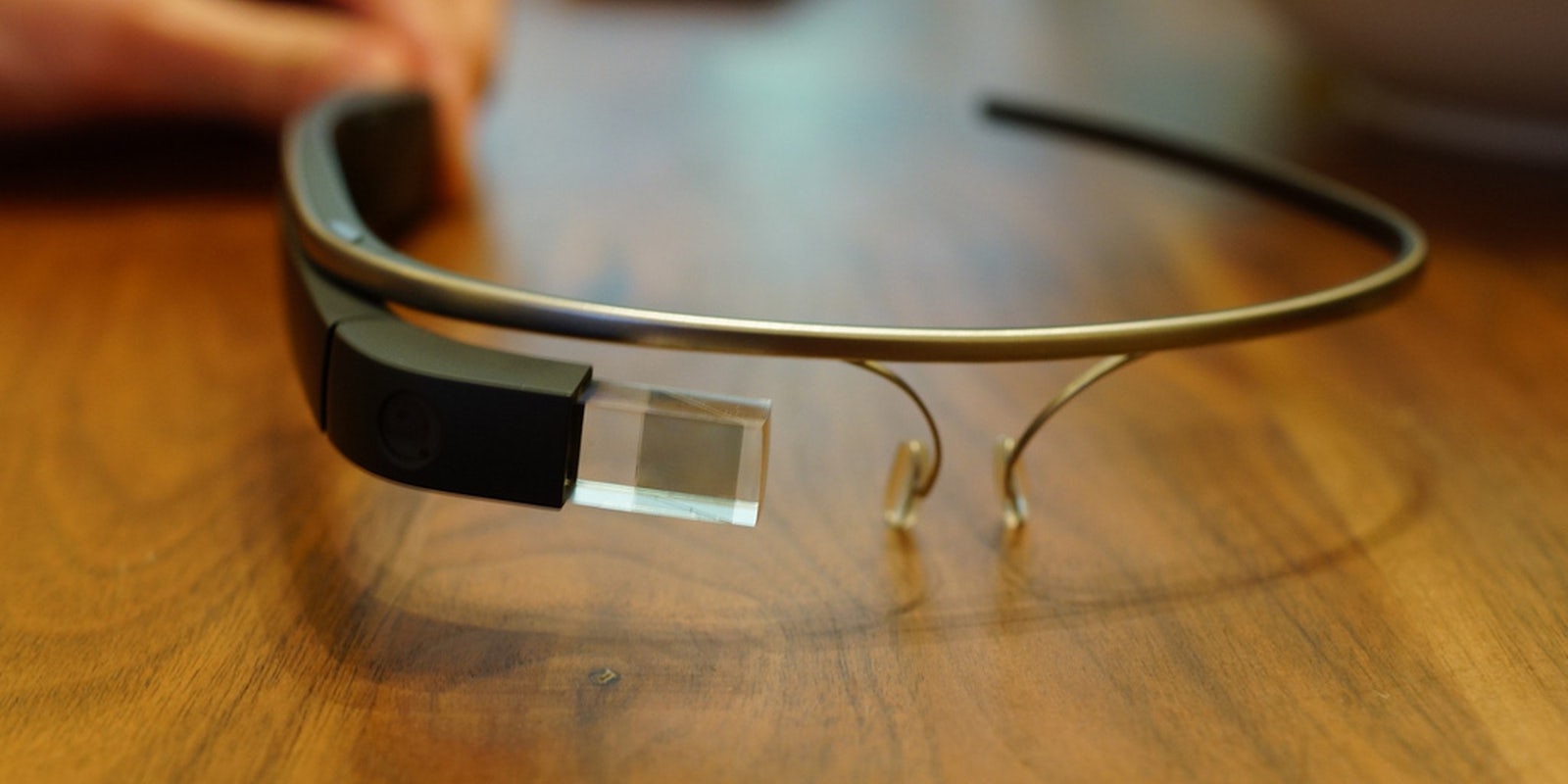

Photo via tedeytan/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)