A funny thing happened on the way to the movies. Last week, my boyfriend and I were attending a late night showing at Film Forum in New York, and the theater was pandemonium. That night boasted the premiere of The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, a documentary about the Black Panthers, the black power movement that was primarily active the 1960s and 70s. You may also remember them from their iconic leather jackets and Afros.

Although the era might be a nostalgic ideal for those who long for the days of disco and All in the Family, it was also a time of revolution—when colonized peoples around the world (including in the U.S.) were fighting for their independence. Because they challenged the power of police to harass and target black people, the FBI classified them as a threat to national security, doing everything they could to silence them.

Many of the film’s attendees were dressed in #BlackLivesMatter shirts, a sobering reminder of just how much the documentary’s racial politics speak to our current cultural climate—in which activists working for racial justice continue to be labeled as a “hate group.” As much as things change, they also stay the same.

Unfortunately, I was not one of these people. I was in the theater next door seeing Rififi, a 1955 film noir by director Jules Dassin. The contrast between the two groups of people was stark—a massive crowd of people of color waiting for a topical documentary on racism in America and the two white guys in line for an old French movie. We went back to see the Black Panthers documentary three days later, but that image stuck with me.

This isn’t the first time I’ve thought about the different versions of the past that the other theatergoers and I are consuming. I got my Master’s degree in film, and my preferred cinematic era is the 1940s and 50s, a time in which people of color played waiters, maids, and butlers—who were either completely subservient, silently pouring the drinks of the white protagonists, or wacky comic relief.

In The Palm Beach Story, one of my favorite movies, a black train attendant—the only character of color in the film—is on hand to gasp with absurd horror while a group of white people shoot at each other, destroying the train around him. Despite the fact that many of his or family members would be subject to horrific violence in a pre-Civil Rights Era South, the scene is allowed to be funny because the movie is not about his story. What’s going on behind his comic mask isn’t considered important.

I firmly believe that this era was the golden age of Hollywood—a time in which studios churned out the movies people talk about when they say that “they don’t make them like they used to.” Films like Witness for the Prosecution, Casablanca, Laura, My Man Godfrey, and Citizen Kane signaled the enormous possibilities of art during a time of Hays Code repression—when even sexuality was taboo and race was all but invisible. How then do you love the past when you realize it wasn’t so golden for everyone?

This critique is behind the recent savaging of Vox writer Sarah A. Chisman. She and her husband are historians of the Victorian 1880s and 90s, who love the era so much that they decided to go method—recreating the period in their home down to the tiniest detail. “Every morning I wind the mechanical clock in our parlor,” Chisman writes. “Each day I write in my diary with an antique fountain pen that I fill with liquid ink using an eyedropper. … There are no modern lightbulbs in our house. When Gabriel and I have company we use early electric lightbulbs, based on the first patents of Tesla and Edison.”

The movie is not about him. What’s going on behind his comic mask isn’t considered important.

For Sarah Chisman, living in a reconstructed past is about the “value in older ways of looking at the world,” but Twitter users quickly pointed out that’s there something more insidious going on.

Michael Darling, who tweets @futurehasbeen, remarked about the writer’s cosplay apologia, “Just to be clear, the Victorian woman doesn’t allow herself to vote, right?” Author and former child actress Mara Wilson joked, “If I lived like my ancestors did in the Victorian era, I’d be dead of famine or pogroms,” before hitting the nail on the head: “Living in the past is a thing only well-off white people can dream of.”

Living in the past is a thing only well-off white people can dream of

— Mara Wilson (@MaraWilson) September 9, 2015

Chisman’s nostalgic fantasies of Victorian life might be extreme, but whitewashing the everyday brutalities of a previous era is incredibly common—and Chisman is hardly the first person to be called out on the Internet for it.

In a post from last week for the Daily Dot, I wrote about the Internet backlash in response to Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” video, which was a love letter to colonial Africa. This was a time—similar to the genocide of Native Americans in the “New World”—in which Europeans who settled in South Africa “dehumanized and traumatized millions of Africans,” as NPR’s James Kassaga Arinaitwe and Viviane Rutabingwa wrote.

The erasure of people of color in her music video might have been unintentional, but it’s also part of her entire appeal. Taylor Swift’s recent music has banked on “classic” images of pop Americana, from James Dean to bright red lipstick. Both of these symbols are featured heavily in her Top Ten hit “Style.” Swift sings, “You’ve got that long hair slick back, white t-shirt/And I got that good girl faith and a tight little skirt.”

When her lyrics argue that “we never go out of style,” it’s not just a matter of her fashion choices but the timelessness of whiteness itself. As Consequence of Sound’s Sasha Geffen writes, “it’s… a song about how young, conventionally pretty white people are always in vogue.”

How do you love the past when you realize it wasn’t so golden for everyone?

This isn’t a just Taylor Swift problem—to an extent, that racial context what we talk about when we talk about “a simpler time,” which was simple because the people who were repressed by that era were, in many ways, unable to challenge the system. Due to systemic forces of segregation, their plight was literally “out of sight, out of mind.”

This thinking was on display during the Washington Redskins controversy in 2014, in which Native groups lobbied the team’s owner, Mark Synder, to discontinue the team’s mascot, criticized as racist. However, Oscar-winner Matthew McConaughey defended the redface depiction. “I love the emblem,” the actor argued. “I dig it. It gives me a little fire and some oomph.”

In his response, McConaughey expressed his own puzzlement with the issue of racism: “We were all fine with it since the 1930s, and all of a sudden we go, ‘No, gotta change it?’” As the Daily Dot’s own Olivia Cole argued, “[T]he ‘we’ he refers to here is very specific, and so is the attitude behind that ‘we.’” Cole writes:

Nostalgic reminiscence about the past is one of the key concepts in white supremacist wishful thinking. McConaughey is not alone in his wistful longing for a time when white people could use whatever slurs they wanted without being troubled by brown people’s dissent. What those who make statements like this think they’re saying is, “I long for the days when people didn’t get offended so easily.” But what they’re really saying—the phrase translated to account for privilege-induced historical blindness—is “I long for the days when the people my racism offended didn’t have a voice.”

No one is telling McConaughey that he can’t admire or be nostalgic about certain aspects of the 1930s or any decade he likes, but appreciating the past means being a critical consumer of its legacy. And it means realizing that there’s an incredible privilege in nostalgia, simply because America he has been taught to long for has been built upon the subjugation and oppression of so many others.

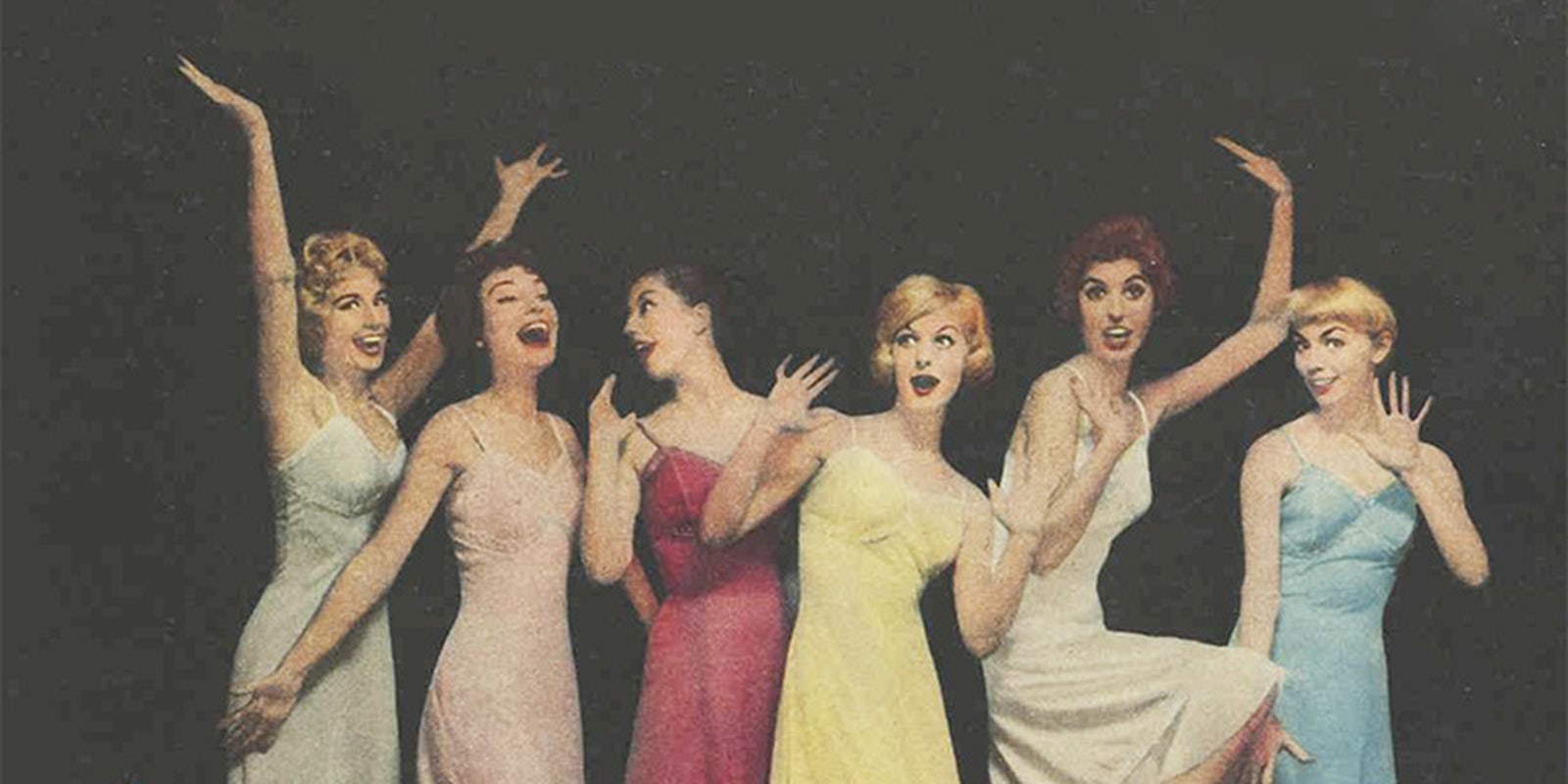

As much as I like the iconography of the 1950s—the bubblegum eroticism of Muscle Beach Party and the pre-ironic simplicity of surf rock—I would never, ever want to live in the ‘50s. As a queer man, this was a time in which my very existence was criminalized as an aberrant pathology. I have the ability to enjoy the era precisely because I don’t live in it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATWUI1eq3G0

A friend of mine and I often joke that we wish we could design an app called “e-racism” that would take all the awkward prejudice and racial caricature out of old movies. That way, you can enjoy all the good parts of Breakfast at Tiffany’s without being reminded about that time Mickey Rooney played Audrey Hepburn’s nosy Japanese neighbor—complete with yellowface. You can live in a world where Song of the South and Birth of a Nation didn’t happen, and Al Jolson never picked up a makeup brush.

But instead of pretending these things didn’t exist, we shouldn’t ignore the worst aspects of the past—creating a version of another period that makes us feel safe and comfortable in our bubble. For folks like Sarah Chisholm, the fantasy might seem simpler, but it’s time to start dealing with the reality.

Nico Lang is the Opinion Editor for the Daily Dot.

Photo via Bess Georgette/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)