Much has been said and written about the rap influences of Hamilton, the hip-hop musical that’s rapidly become a true cultural phenomenon. But newcomers to the Broadway scene might find themselves unfamiliar with many of Hamilton‘s core musical-theater influences—and there are plenty.

If you’ve fallen down the rabbit hole of political musicals, rock musicals, or the collected works of Lin-Manuel Miranda, we don’t blame you. Luckily for you, Hamilton is a revolutionary upstart standing on the shoulders of other revolutionary upstarts. Here are our picks for the 10 musicals that most directly influenced Hamilton.

1) Assassins

Stephen Sondheim‘s most scathing critique of America, a look at the lives of people who have attempted to assassinate U.S. presidents, failed to make it to Broadway twice before finally doing so. Despite sold-out previews, the production folded in its original run because its strident deconstruction of the American Dream was considered too anti-patriotic just as the Gulf War was beginning. A second attempt to bring the show to Broadway was fatefully scheduled to begin rehearsals in September 2001; it wasn’t until 2004 that Broadway welcomed this odd, discordant, and deliberately ambiguous ensemble musical.

In Assassins, Sondheim and librettist John Weidman scrutinize the idea of a historical narrative, and especially what it does to those who are excluded from it and those who are desperate to write themselves into it. These themes are crucial to Hamilton—so much so that, while working on it, Miranda actually consulted with Weidman about his approach to writing the book for Assassins.

2) Jesus Christ Superstar

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-voeq7Cebo

Hamilton makes no secret of its debt to Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, two early Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals about political figures told from the perspectives of their primary antagonists. The character of Burr in Hamilton is a direct descendent of Jesus Christ Superstar‘s Judas: They each begin as friends of the hero but ultimately become the villains in their respective histories. Each musical shows an antagonist attempting to reclaim his side of the story by narrating the show—though whether they succeed is ultimately up to you.

3) Rent

Rent is Hamilton‘s spiritual twin. Both musicals use the language of contemporary music to tell the story of groups of marginalized people—the underprivileged, the poor, the immigrants. Rent depicted hipsters, junkies, AIDS victims, people of color, and queer and transgender characters—a range of realism rarely seen on the musical-theater stage before 1996. Hamilton likewise is explicitly bringing actors of color to the stage and folding people of color back into a narrative from which they have historically been excluded.

Like Hamilton, Rent used its narrative of a past cultural moment to speak to a present one. And like Rent, Hamilton has completely electrified that cultural moment and reached beyond the typical musical-theater crowd to speak to a generation.

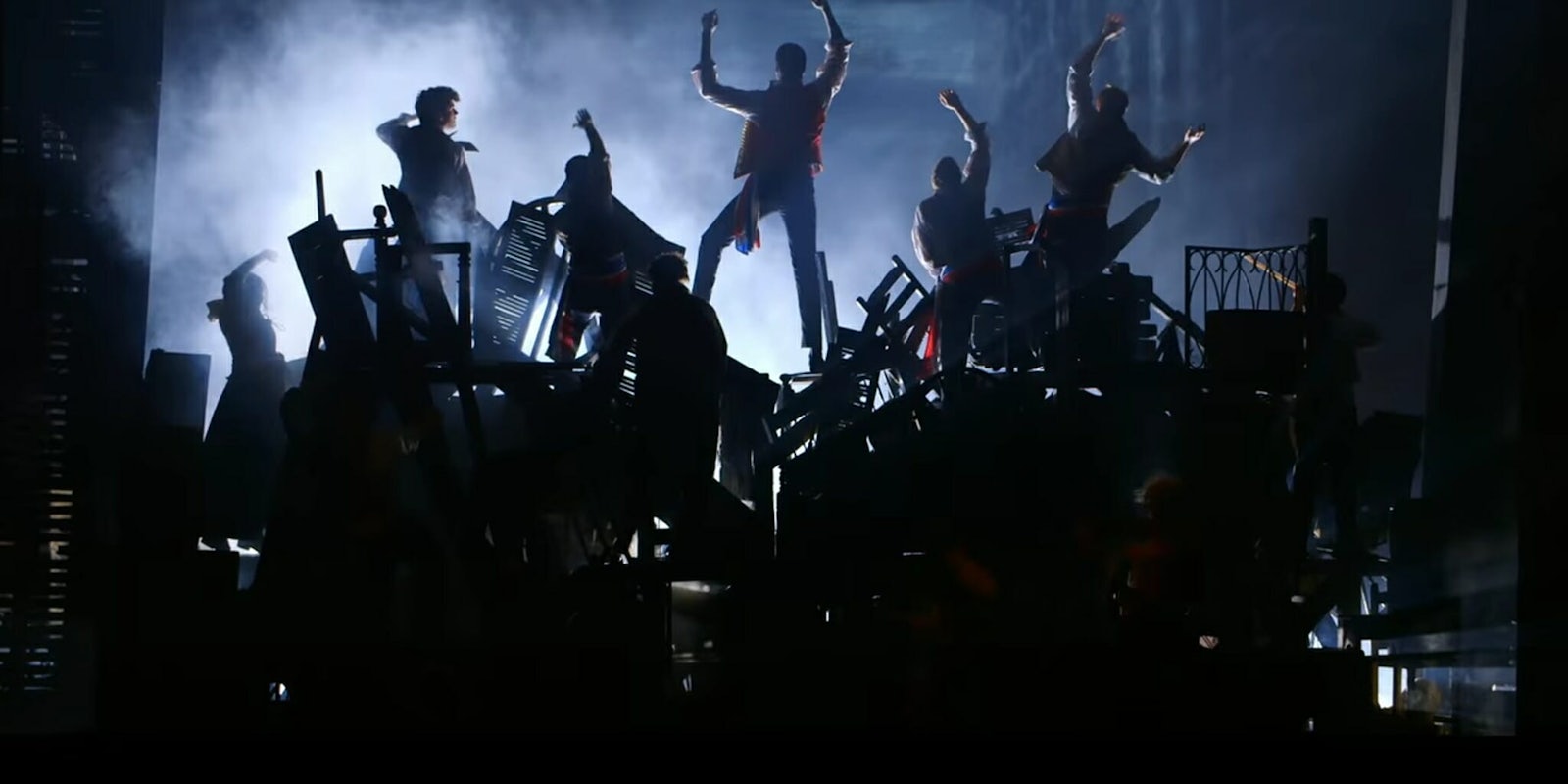

4) Les Misérables

A musical so popular Broadway seems determined to just keep reviving it endlessly, Les Misérables is the first musical Miranda saw on Broadway and the one he credits with making him want to write musicals. Les Mis made the topic of political uprisings an appropriate subject for the stage long before Hamilton. Fans of the latter have wondered if the tavern scenes in which Alex and his new friends drink to the revolution are a deliberate homage to Les Mis, though Miranda has said that this is just a coincidence.

Still, there are plenty of common themes in both musicals: the underprivileged making political stands, students eager for war, and oppressive governments far removed from the everyday concerns of their subjects. Given how much love the two current productions have for each other, and what a huge Les Mis fanboy Miranda is, it’s obvious where he got his revolutionary spirit.

5) 1776

1776 is the other musical to tell the story of the American Revolution, and there’s a lot going on in the interplay between it and Hamilton. Both musicals spend their time humanizing the Founding Fathers, but to very different ends. In 1776, John Adams is the story’s clear hero, with Jefferson serving as his right-hand man; in Hamilton, Adams isn’t even on stage, and Jefferson all but twirls a villain’s mustache.

In 1776‘s opening number, titled “Sit Down, John,” the other members of the Continental Congress refuse to listen to his entreaties to consider a vote for independence. Hamilton likewise begins in 1776, but the Declaration has already been completed, Adams is on the sidelines, and Hamilton has other action on his mind. In reality, Adams and Hamilton hated each other, so when, in Hamilton, the title character yells, “Sit down, John, you fat mother—!” it’s a fair summation of their relationship.

But more importantly, Hamilton conscientiously rebukes the personalized but reverential view of the Founding Fathers that 1776 espouses. Miranda is affectionately telling 1776 to sit down and let a new, more relevant narrative take over. In the recent skit he wrote for The Late Show, he plays John Adams in a tongue-in-cheek Easter egg—sitting down, of course.

6) Pacific Overtures

Another Sondheim musical with a libretto by Weidman, Pacific Overtures is the musical-theater legend’s most notorious flop, but it nevertheless cast a long shadow. Though it’s rarely performed today, this story of the Japanese treaty with Admiral Perry that irrevocably ended the country’s isolationism contains powerful themes like class tensions, political conflicts, cultural erasure, and the question of authenticity of narrative.

The climax of Pacific Overtures occurs during a song called “Someone In a Tree” that narrates the signing of the treaty from the perspective of innocent bystanders. The song examines the impossibility of knowing what happened during the signing, but like Assassins, it also explores the desires of the bystanders to write themselves into the narrative of the event. If that reminds you of Aaron Burr trying to get inside “The Room Where It Happens,” it should.

7) Camelot

This is one of Miranda’s favorite musicals, and its story has more in common with Hamilton than you might at first imagine: tenuous friendships, the complications of government, personal betrayal, and relationships torn apart by passions and politics. Oh, and lots of beef and bass.

8) South Pacific

Another story of historical conflict in the Pacific, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s examination of racial politics during World War II is still relevant today. The song “You’ve Got To Be Carefully Taught” was nearly cut from the film version of the musical because producers feared it might be too incendiary—but it survived and became the show’s enduring statement on racism as a product of systemic prejudice.

In his first meeting with Hamilton, Burr quotes the title of the song in an ironic context: “You’ve got to be carefully taught—if you talk you’re gonna get shot.” This establishes Burr’s character as an embodiment of respectability politics, while echoing South Pacific‘s pessimistic acquiescence to the way things are. It’s a grim reminder that U.S. racial politics have only changed modestly since the 1940s.

9) In The Heights

Miranda’s first Broadway musical bears many similarities to Hamilton. Set in a Washington Heights community much like his own, In the Heights uses Latin music and hip-hop influences to communicate the story in the vernacular Miranda grew up with. As in Hamilton, Miranda also starred as the lead character, Usnavi, a man who, like Hamilton, has to balance his dreams of something bigger with his attention to his family and his community, plus his desire to be true to his Caribbean immigrant heritage.

Like Hamilton, In the Heights is self-aware and referential. The musical’s opening three musical notes are a direct quote, or sampling, of the beginning of “America” from West Side Story. With this quote, Miranda announces the theme of the musical—identity, heritage, and the conflict between two islands, Puerto Rico and Manhattan. But it also inserts him into the larger narrative of musical theater itself, allowing him to stake a claim for himself (and Puerto Rico) next to Bernstein and Sondheim. It’s a brash, bold, upstart move, full of energy and genius.

Who does that remind you of?

Screengrab via Les Misérables/YouTube