BY IAN BELKNAP

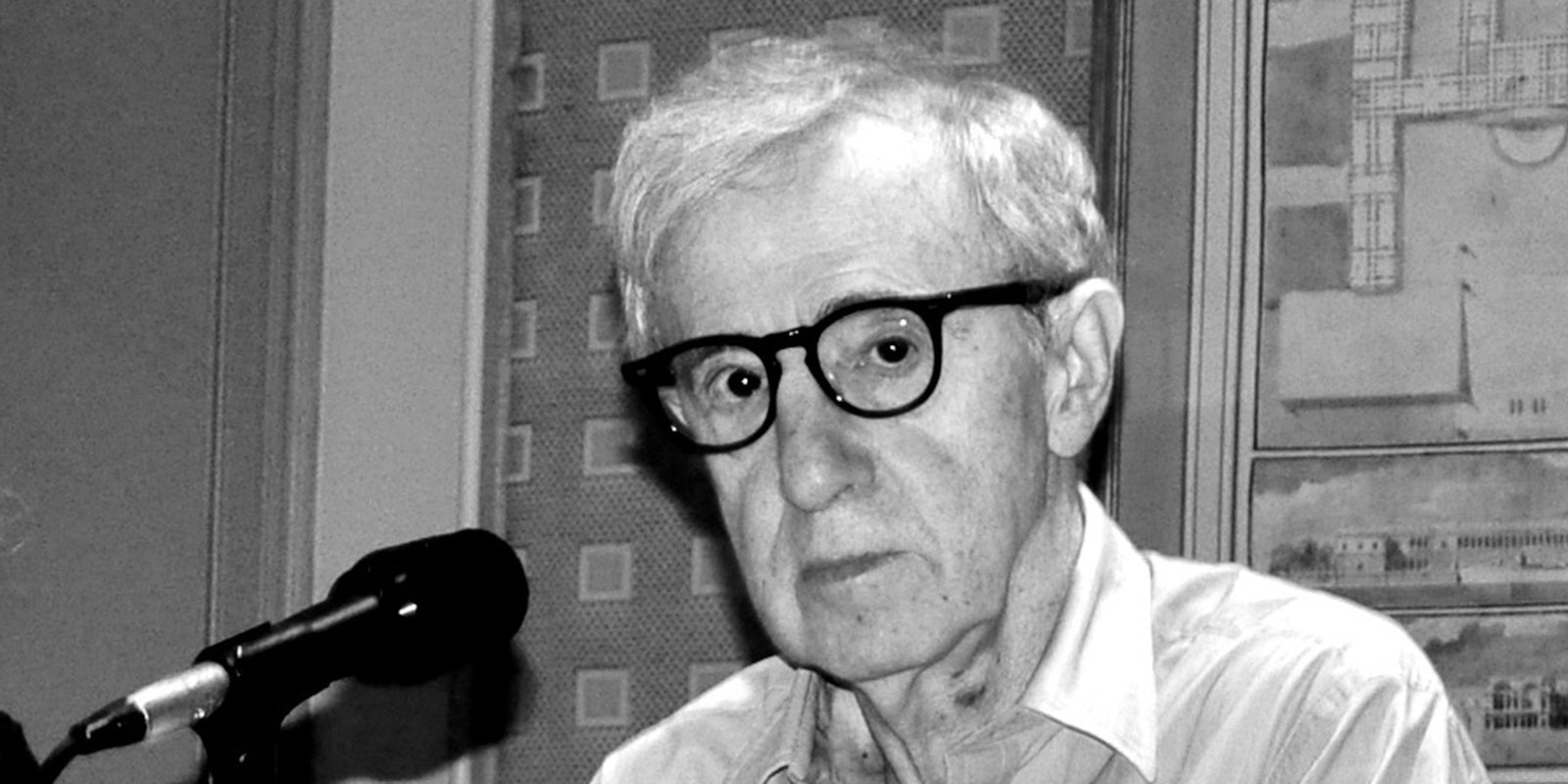

Buried in its breathless star-tremors, Gawker drew a false equivalency between the conflicted-sounding smattering of applause for Matthew McConaughey’s shout-out to God during his tribute to his own heroism and the conflicted-sounding smattering of applause at the mention of Woody Allen’s name during Cate Blanchett’s acceptance speech. In an article posted on Monday, Gawker’s Max Read asked, “Which ancient, neurotic pervert got more applause at the Oscars on Sunday night—Woody Allen or God?” Given that Read felt the need to pose the question, you can probably guess his answer.

While there is a click-baiting, outrage-fomenting logic to this argument (“those heathens in Tinseltown think as much of an alleged pedophile as they do about God!”), it does not ring true to me. If you listen carefully, yes, both smatterings are tinged with shame, and one can make out each faint and reluctant palm-smack. The God-shame probably has something to do with the panic of losing market share in the fly-over states that cling quaintly to faith of whatever sort, but to my ear, the Woody Allen smattering was more richly layered and complex.

For decades now, the stately passenger cars of Allen’s film work have been on a collision course with the squalid freight train of his personal life. This collision is not what we hear during Sunday night’s Oscars telecast—there was no deafening crash, no shower of sparks. The Oscars represented a conspicuous and transnational chance to either exonerate or excoriate Allen unequivocally, but neither took place, really. It could have been a “manning the ramparts in defense of artistry, no matter the indiscretions or accusations surrounding the artist.” This very much was not the case, but neither was it a “denunciation of privilege abuse that makes clear we, the film industry, believe there are larger considerations than our little projects, and we stand in solidarity with those who have been victimized.”

I can’t claim to have direct knowledge of Mr. Allen’s alleged misconduct—I wasn’t in that Connecticut house when he did or did not touch a child in unacceptable ways. Nor can I claim to be equipped to tell retroactively which of them is telling the truth. But I am an observer of my world, and what I heard in the smattering was an auditory glimpse at a tenuously connected community (to the extent that tethers of ego-strokes and money constitute connection) attempting and failing to serve several masters.

On the one hand, Hollywood royalty is exquisitely attuned to what they imagine regular folks care about; they wish to appear to have zero tolerance for kid-groping. On the other hand, though, Woody is one of their own. And Hollywood is a like a mill town where all economic activity (and therefore its truest allegiance) hinges upon the weekend box office for “Thunder Cats VII: Spay Your Enemies” or its synergistic, toy-licensing-and-product-placement-ing equivalent.

Where Hollywood differs from a mill town is in its abiding and oxymoronic insistence that we recognize its artistic achievements—hence the slavering circle jerk of awards season. And aside from maybe Harvey Weinstein, Woody Allen is the most frequent cover boy on the trade paper/stroke mag “Prestige-y: A Journal of Middlebrow Content For the Risk-Averse Gentleman.” It’s like if West Virginia, which makes its real money from slicing off the tops of mountains to extract the coal, were to gather each year to sing the praises of small-batch, artisanal coal that nobody actually uses, or a dockworker who keeps trying to convince you his brawny efforts are actually a branch of the humanities.

So, given this peculiar environment, there is to be an expected circling of wagons, which you can hear in Sunday’s applause smattering.

In it, you hear the dismayed anguish of the seat fillers who seek in vain to express their unanimity with the bespectacled bard, even as they fear a backlash at the box office. If you go back and listen to the clip with your eyes closed, you can easily imagine it as the sort of torn applause you might hear from a crowd of soldiers for a general rumored to be a cannibal, or for a grade school play about Dr. Mengele. It is the careening-between-impulses kind of ovation you’d expect to hear when the baton-twirler barfs into the orchestra pit, or the spelling bee victor has an outburst of Tourette’s.

I don’t believe Hollywood to be an immoral place, in the Bible Belt sense of the phrase. It is rather an amoral place, a place bowed by the lash of the bottom line. A place where you’re constantly in league with shitty, vindictive people with a stranglehold on your economic prospects. So you compromise and diminish yourself by inking deals with the devil. And it is this amorality that leads ultimately to a damaging form of immorality—not one of bawdy godlessness, but of relativistic opportunism. The baffled and betrayed-sounding smattering was less about the particulars of the Allen case than it was the sucking sound made by a bunch of laborers as they were swallowed by moral quicksand.

Ian Belknap is Founder and Overlord of Chicago’s WRITE CLUB. Belknap is also the writer and performer of his own solo shows, including “Bring Me the Head of James Franco, That I May Prepare a Savory Goulash in the Narrow and Misshapen Pot of His Skull.” He teaches writing for performance and Live Lit at StoryStudio Chicago and elsewhere.

Photo via rasdourian/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)