When George Orwell and Ray Bradbury penned books such as 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 to warn the world that Big Brother is watching, they probably never would have guessed that most people would grow to like it.

Government surveillance and intrusion is a tale as old as time—from Biblical stories of King Herod’s infanticide during the birth of Jesus Christ to COINTELPRO tracking the moves of civil rights activists such as Martin Luther King. Indeed, most snooping isn’t part of an elaborate, fantastical program; it’s just considered business as usual. As Trevor Timm noted at the Guardian last year, local law enforcement agencies and the Obama administration have reportedly used cell phone location data to track people in their homes—often without a warrant—further enabling police militarization. And that’s in addition to the NSA’s surveillance program.

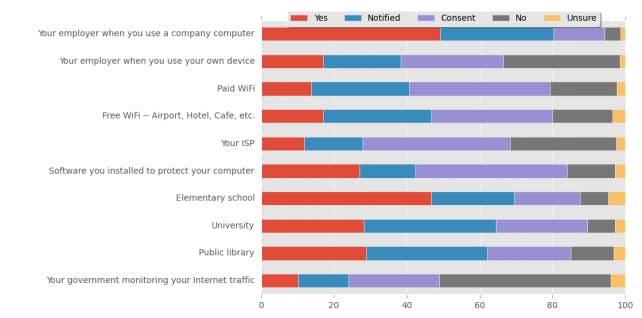

Yet as the Daily Dot’s Patrick Howell O’Neill reports, a recent survey found that most Americans would actually be OK with many kinds of snooping, as long as the snoopers gave them a heads up. The survey, titled “At Least Tell Me,” found that only half of all respondents outright objected to warrantless government surveillance, with roughly the other half either accepting it without qualification or requesting some kind of notice or consent.

On the whole, the survey shows that most Internet users in the U.S. have a fairly relaxed, if not informed definition of online surveillance. Internet users lump in employers, schools, and libraries alongside the likes of Internet service providers, social media companies, and the government. And it’s time that the Internet learned what surveillance is and what it isn’t.

Surveillance, as it’s most commonly understood, involves an intentional, deceptive violation of privacy, where behavior is monitored to manage or manipulate information toward a strategic end. It could be as simple as an Internet company protecting its network and users from malicious hacking attempts. Or, it could be as nefarious as one’s political opinions—regardless of whether they’re shared in a public forum or a direct message—finding their way on the radar of a clandestine tracking algorithm that targets social movements.

The survey shows most American Internet users have a fairly relaxed, if not obscure definition of online surveillance.

But per the survey’s results, it’s clear that the public feels that not all Internet snooping is created equal. A majority of respondents support employers and schools monitoring Internet usage on their systems without qualification, followed closely by universities, public libraries, and user-installed software for computer protection. But the tune changes considerably when it’s a matter of either free or paid Wi-Fi connections, an Internet service provider, or the government.

While respondents conceded that organizations need to protect their information technology, the results show there’s no hard-and-fast approach to understanding Internet snooping. But to call a school or a company’s content filters, data protection, and other protective IT measures “surveillance” waters down the definition. Any workplace or learning institution worth its salt would constantly remind community members—usually with a login prompt—that they should have no expectation of privacy on the company’s networks.

In that case, it’s not a violation of privacy, it’s not deceptive, and it’s not necessarily intrusive. After all, if an individual doesn’t abide with the terms of usage, they have every right to not use the network, even if it could place their job or academic career in jeopardy. Where there’s both notification and consent to monitoring, surveillance is hardly the best way to describe the situation. If you know you’re being watched, and you consent to being watched, then you are simply being watched—but you’re not necessarily being surveilled.

Although survey responses were skewed given relatively high participation of young adult, single, childless males—most of whom considered themselves Internet security savvy, as O’Neill noted—these attitudes about surveillance are one thing coming from a demographic with a notably high engagement with technology. It’s a different story when considering the Internet at large and users who may not be as savvy about privacy matters.

When there’s notification and consent to snooping from any source, users on those networks are equipped with information as to modify their usage to meet the standards of their employer, school, ISP, or their community. If corporate tracking software keeps tabs on how much employees spend on websites unrelated to one’s job, they may be better served using their smartphone to keep tabs on entertainment news instead of using their workplace web browser.

And if any employee behaves otherwise, and gets called into a meeting about their workplace productivity issues, they can’t say they’re surprised or appalled when the data becomes part of the discussion. After all, there was plenty of warning.

Porn-blocking and tracking software on a school computer is a world of difference from police officers tripping data towers for information.

The same could even be said of online methods of communication. Aside from select browsers and methods of data encryption that work as roadblocks for hackers, and potentially for law enforcement, most users should have no expectation of privacy on any online platform—no matter how much the companies who use them assure ironclad security. The hacks of Ashley Madison, major retailers, influential users on Twitter, and alleged government spying on Black Lives Matter activists, to name a few examples, show that even “private” communications can find their way into hands of unintended recipients, without the user’s knowledge.

But unless individuals wish to go off the grid, to protect their information while leaving little-to-no digital paper trail, there’s not much to be done other than self-educate and use the best resources available for privacy protection online. Instead of volunteering information, like every time Facebook sends a nagging alert, consider ignoring the requests or bypassing them if possible. More often than not, there’s plenty of information users could avoid providing while still enjoying their Internet usage as usual.

With or without notice of snooping or monitoring, it’s important to be specific and clear about what we mean when we talk about surveillance. In order to best discuss how Internet privacy and protection can work best for every kind of user, it’s important to isolate what kind of monitoring happens and under what conditions. Because porn-blocking and tracking software on a school computer is a world of difference from government officials tracking your every digital move.

Derrick Clifton is the deputy opinion editor for the Daily Dot and a New York-based journalist and speaker, primarily covering issues of identity, culture, and social justice.

Illustration by Max Fleishman