In El Salvador, homicide isn’t some distant problem you read about in headlines or see in televised entertainment. Horrific acts of violence are frequent, observable, and widespread. MS-13 and the 18th Street gang, two rival criminal organizations that originated in the United States, terrorize the population, leaving the bodies of their victims not only in the streets but hidden throughout the countryside.

The Engineer, a new documentary produced by filmmakers Juan Passarelli and Mathew Charles and funded in part by WikiLeaks, centers around the brutality of gang violence in the area. The cast of The Engineer are the neglected dead, the victims who’ve mysteriously vanished.

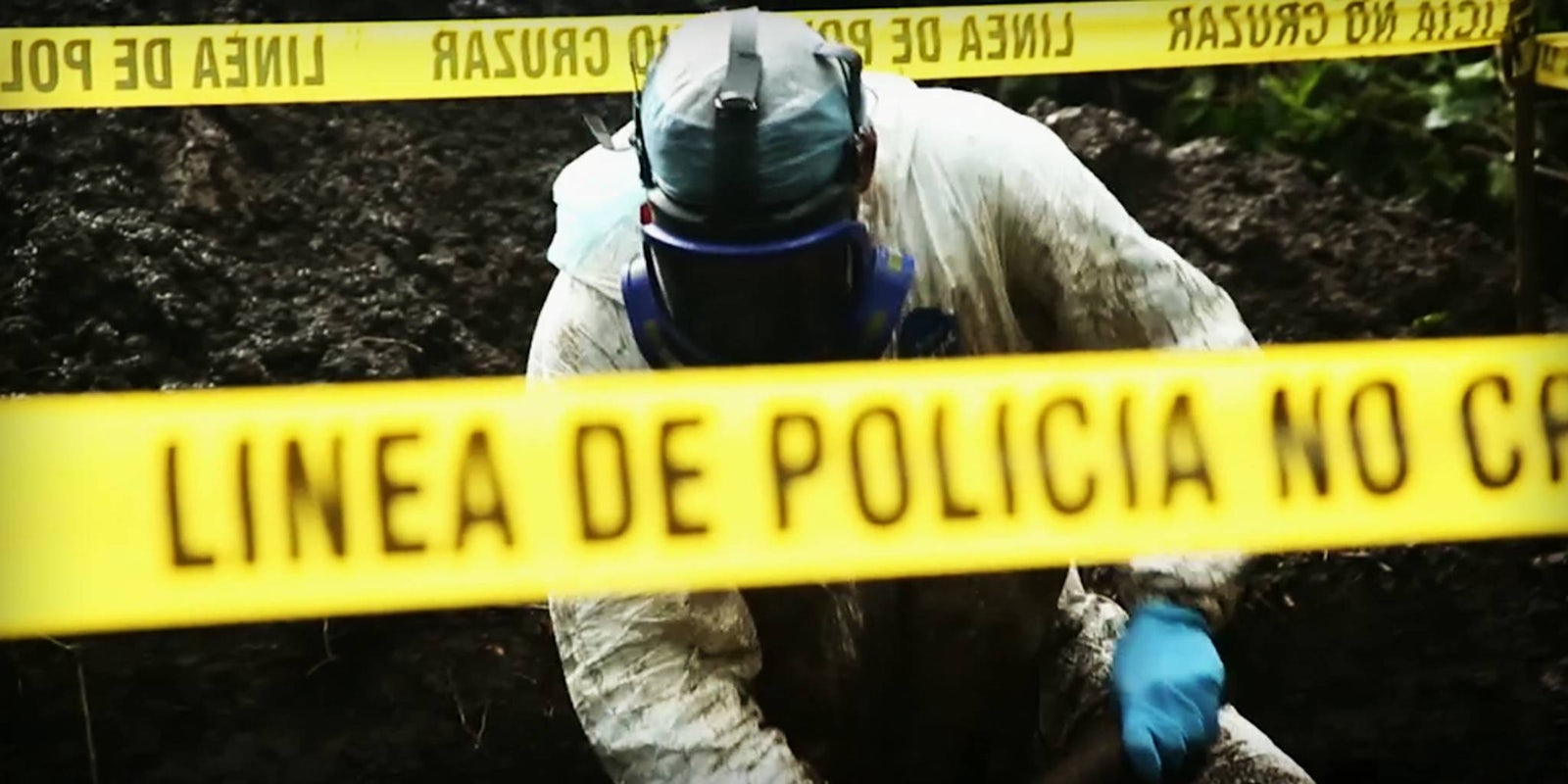

The film opens with Israel Ticas, the only criminologist in El Salvador, a country with one of the highest crime rates in the world. As a forensic investigator and pathologist, he’s charged with locating, exhuming, and identifying what he calls the “disappeared.” WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has described him as “a real-life CSI detective.”

Es un honor el servir a mi pueblo desde la Fiscalia, siempre arriesgare hasta mi vida por cumplir mi mision. pic.twitter.com/FKpF1aYwCr

— Ing. Ticas (@IngenieroTicas) October 22, 2013

According to The Engineer, a truce has been brokered between MS-13 and the 18th Street gang in El Salvador. But while there’s been a reduction in the official estimates of violent crime in the state—the average number of homicide victims lowering from 14 to six per day—it’s revealed that gang members have simply changed tactics to maintain appearances, concealing evidence of their crimes. They discard their victims by throwing them down abandoned wells or digging graves in remote locations, unlikely to ever be discovered. While politicians celebrate a declining murder rate in the media, the number of missing men, women, and children in El Salvador continues to rise.

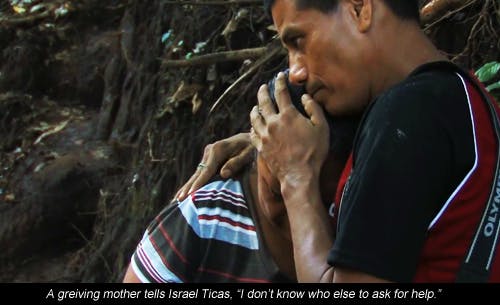

Ticas compares his work to that of an archeologist. He methodically searches for and collects the dead, with the help of volunteers known as the “Brigadas ALFA.” He’s often accompanied in the fields and forests by the mothers of the disappeared. He calls them the victimas secundarias, or the secondary victims, who are seeking a sense of closure, no matter how painful it might be. They call him “El Ingeniero” (the Engineer).

It’s through Ticas’s work that the extent of the issue is revealed. His office in San Salvador is covered in grisly photographs of the dead in varying stages of decay, some unspeakably mutilated. In the town of Turín, he planned and oversaw an excavation that he claims was the largest in Latin America and the largest in the world resulting from a homicide.

“When you think about the 20 mothers waiting for the bodies down there, that’s when you get motivated.” Ticas tells his construction crew at one point. “Also, we will save many lives doing this, because if we don’t get those bodies out… it’s no joke, 42 men will go free.”

Several scenes in The Engineer will take your breath away. The filmmakers eventually sit down with Salvadoran gang members who are cooperating with authorities while under witness protection. Many of these killers admit to claiming their first victims before they were even teenagers. One of the younger ones, his face hidden under a black balaclava, tells the film crew that he’s personally murdered over 20 people and doesn’t consider himself a serial killer. The bar, he thinks, should be raised to 60 victims, demonstrating how little the Salvadoran gangs value human life.

Asked what the gangs think of Ticas’s work and whether they ever consider murdering him, one gang member responds: “He’s sticking his nose where it doesn’t belong,” the youth says. “If they had the opportunity to capture you, they’d put you underground and wait to see if your colleagues dig you out.”

He then awkwardly apologizes to Ticas.

“No offense,” he says.

Ticas admits that he has dreams in which he dies from a bullet. He says his death won’t come naturally. Amazingly, his son, who attends law school in San Salvador and frequently joins Ticas in the field, is ready to take up his father’s cause.

“It’s good to learn, mostly to try and take some of the pressure off, because it’s only him out here,” says his son, whose face is blurred in the film.

The purpose of The Engineer isn’t to shock the audience as much as help them understand the exceptional viciousness of the MS-13 and the 18th Street gangs. The unprecedented level of gore in the film may make some people uncomfortable, but it’s required.

The first step to solving any problem is to admit it exists. Statistics are being used to cover up bloodshed in El Salvador. The Engineer helps expose some of the truth.

Screengrab via The Engineer