This post contains spoilers for Sorry to Bother You.

Boots Riley would have won the 2016 Democratic Primary.

Riley, the writer and director of Sorry to Bother You, has created something special with his debut feature film. Not only will the movie rank among the best of the year, but Sorry to Bother You also serves as a primer for how to approach our political moment. Riley and the story he’s telling understand intersectionality better than pretty much any politician in America.

Intersectionality is defined as “the complex, cumulative manner in which the effects of different forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect.” While this is a relatively easy term to define, it is can be difficult to illustrate what intersectionality looks like in the real world.

The political visions of various candidates, even with the best intentions, often fall short when it comes to intersectionality. For example, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), whose economic message resonated with many Americans, was often criticized for not focusing enough on race and gender during the 2016 primary race. Hillary Clinton took heat for her shortcomings when it came to both race and class.

Sorry to Bother You deftly addresses issues of race, gender, and class with equal weight, carefully analyzing the way they play out in society, and offering solutions that take all three into account.

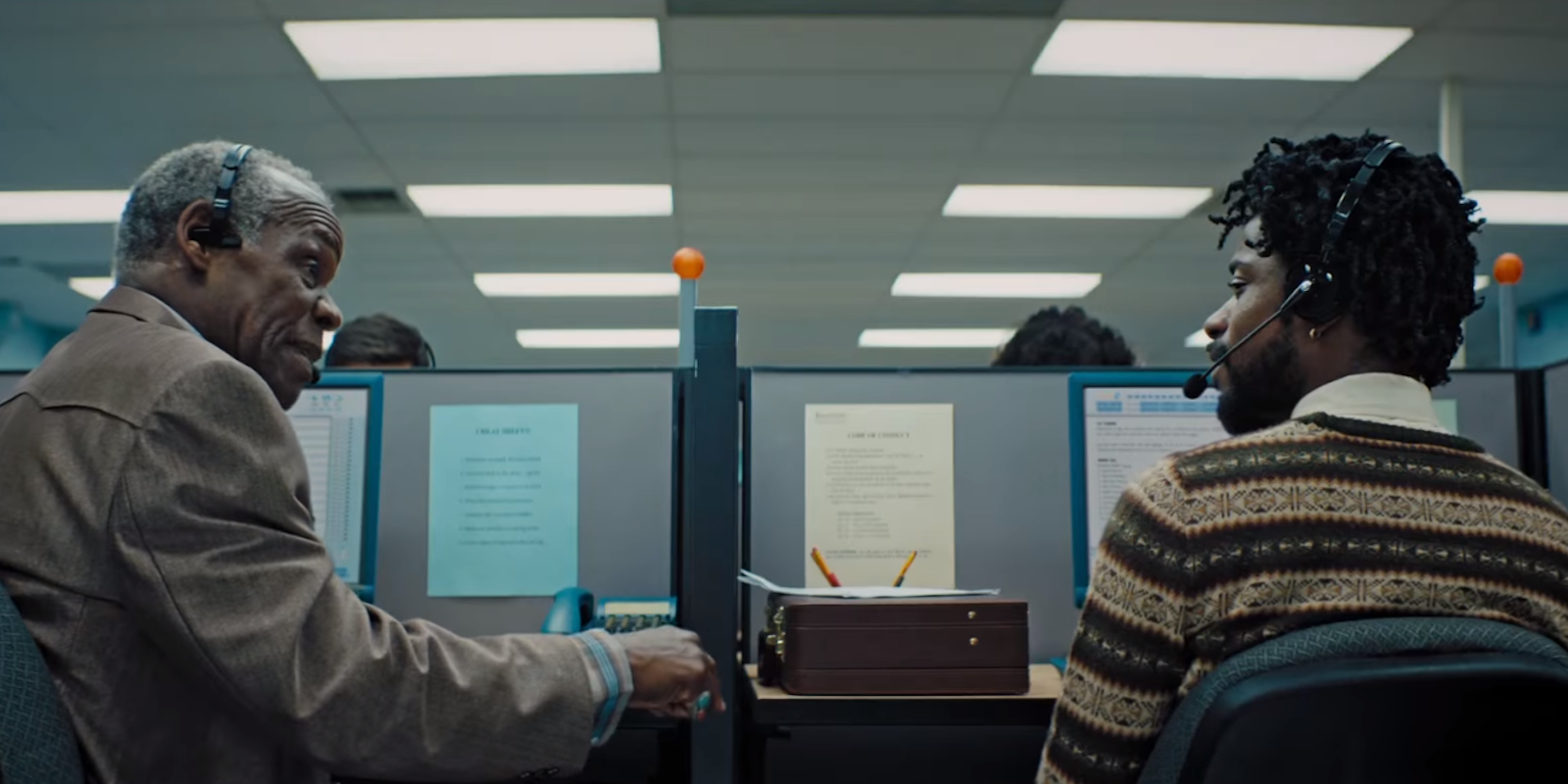

Lakeith Stanfield plays Cassius “Cash” Green, a young Black man who is down on his luck and deep in debt. All of that changes when an older mentor at his new telemarketing job, Langston (Danny Glover), teaches him how to use his “white voice.”

Langston tells Cassius that a white voice, “Sounds like you don’t have a care in the world. I got my bills paid. I’m going to jump in my Ferrari after this call.” He continues, “It’s not really a white voice. It’s what they think they are supposed to sound like.”

Here, the white voices are literally dubbed over by famous white actors like David Cross and Patton Oswalt to hilarious effect. But, with this surreal conceit, Riley is talking about something very real in society: code-switching. Code-switching is the practice of “shifting the languages you use or the way you express yourself in your conversations” that Black people, other minority groups, and really any oppressed group, engages in every day.

Speaking like an upper-class, middle-aged white man can be a key to unlocking power in a society dominated by them. Once Cassius code-switches, he becomes a successful telemarketer. He has a clear-eyed understanding of how race functions in society and he takes advantage of it. Soon enough, he rises through the ranks to become a “power caller,” an elite salesman who spends his days high up in the building fawned over by underlings, praised by computer assistants, practically ruling the world.

Things are going so well for Cash that he refuses to recognize that maybe things are too good to be true. He is blinded by his newfound wealth and the flattery of co-workers who pay him absurd, hyper-capitalist compliments like, “35 percent of men who wear pink are more likely to start a franchise.” As he ascends a golden elevator into the world of the power callers, he doesn’t have much time for the co-workers he’s left behind.

Everything goes well very well for our hero… until it doesn’t.

Before we get to how exactly Cassius gets more than he bargained for, let’s talk about Cash’s girlfriend, Detroit (Tessa Thompson). A hip performance artist, Detroit practices an assertive brand of feminism. She wears shirts that say “the Future is Female Ejaculation,” and sports massive earrings shaped like penises. Her performance art is rooted in challenging the patriarchy: She orders her patrons to throw bullets and cell phone components at her nearly naked body in the most overt critique of toxic masculinity this side of Lindy West.

But, unlike Cash, Detroit is not myopic. Her art is also rooted in race: Her gallery show features various wooden renderings of Africa, meant to critique colonialism. She also has deep class consciousness, moonlighting as an antifa-esque radical. Unlike Cash, she sees beyond the individual and considers a multitude of people in her work and her social life.

Detroit practices the kind of intersectionality that Cassius has to learn the hard way.

While Cash is focused on becoming a power caller, his Asian-American co-worker Squeeze (Steven Yeun) and his best friend Salvador (Jermaine Fowler) are busy trying to unionize the call center employees at Regal View. Squeeze is salt, someone who takes job as an employee at a company in hopes of forming a union. Salvador is his zealous new recruit.

Squeeze convinces the call center employees to stage a work stoppage and then convinces them to walk off the job altogether. Cash, now one of the top power callers, crosses the picket line.

Detroit gives Cash an ultimatum. She tells him, “It’s one thing to take a promotion, but you’re a full-out scab. You crossed the picket line… If you go to work today and cross that picket line, we’re done.”

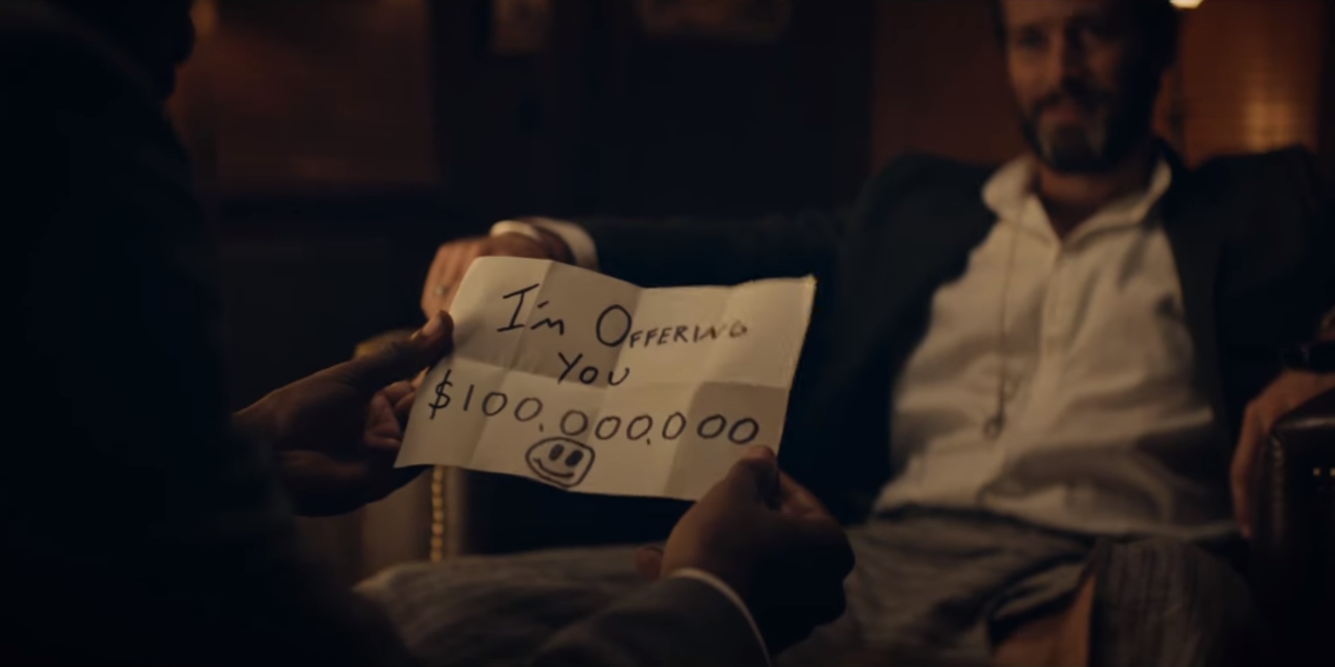

He makes the wrong choice. From here, Cash drifts into the orbit of the CEO of the mysterious Worry Free corporation, Steven Lift (Armie Hammer), as he learns the harsh realities of being a power caller. Power callers sell power, in the form of arms, drones, and even people. Worry Free is one of Regal Views’ biggest customers, an unholy mix of Amazon and a debtors’ prison that is slowly taking over the world.

As Cash learns the truth, he also realizes that he isn’t actually as valued as he once thought. The mostly white Worry Free staff laugh as Lift asks Cash if he ever “busted a cap” in anyone and then force Cash to rap for him. Cash had to sacrifice his identity to climb the corporate ladder, and now his Blackness is being used to excuse Worry Free’s racism.

Cash stumbles upon the real plan for Worry Free: Developing half-man, half-horse workers for their slave labor force. Lift wants Cash to become an “equisapien Martin Luther King Jr.” He wants Cash to act as a corporate spy, to sell out his people and become a class traitor.

Finally, Cash sees the truth. He rejoins the picket line and joins forces with the horse people. His politics that were once incredibly individual have evolved into something wholly intersectional. Riley is careful to highlight the racial and sexual inequality that exist in Regal View and Worry Free, reinforcing that equality by any measure isn’t possible with true intersectionality. There are women. There are Black men. There are Asian men. There are even horse people. And unless they work together toward their common interest, they will be controlled by mad men from Silicon Valley, Wall Street, or D.C.

Sorry to Bother You perfectly mirrors our political moment. When you see the diverse cast leading dozens of workers on strike, the image isn’t far off the solidarity exhibited by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in her surprise New York primary victory; by Therese Patricia Okoumou, who was arrested on July 4 during her anti-ICE protest at the Statue of Liberty; or by ADAPT protesters fighting Trump’s healthcare reforms.

There are a number of explicit moments in Sorry to Bother You that drive home the concept of intersectionality, but none of them are quite as poetic or absurd as one near the end of the film. Squeeze, Detroit, Salvador, and Cash have triumphed with the help of the horse people. Squeeze, who had the right idea all along, looks at one of them and says, “Same struggle. Same fight.”

And the horse man knows exactly what he’s talking about.