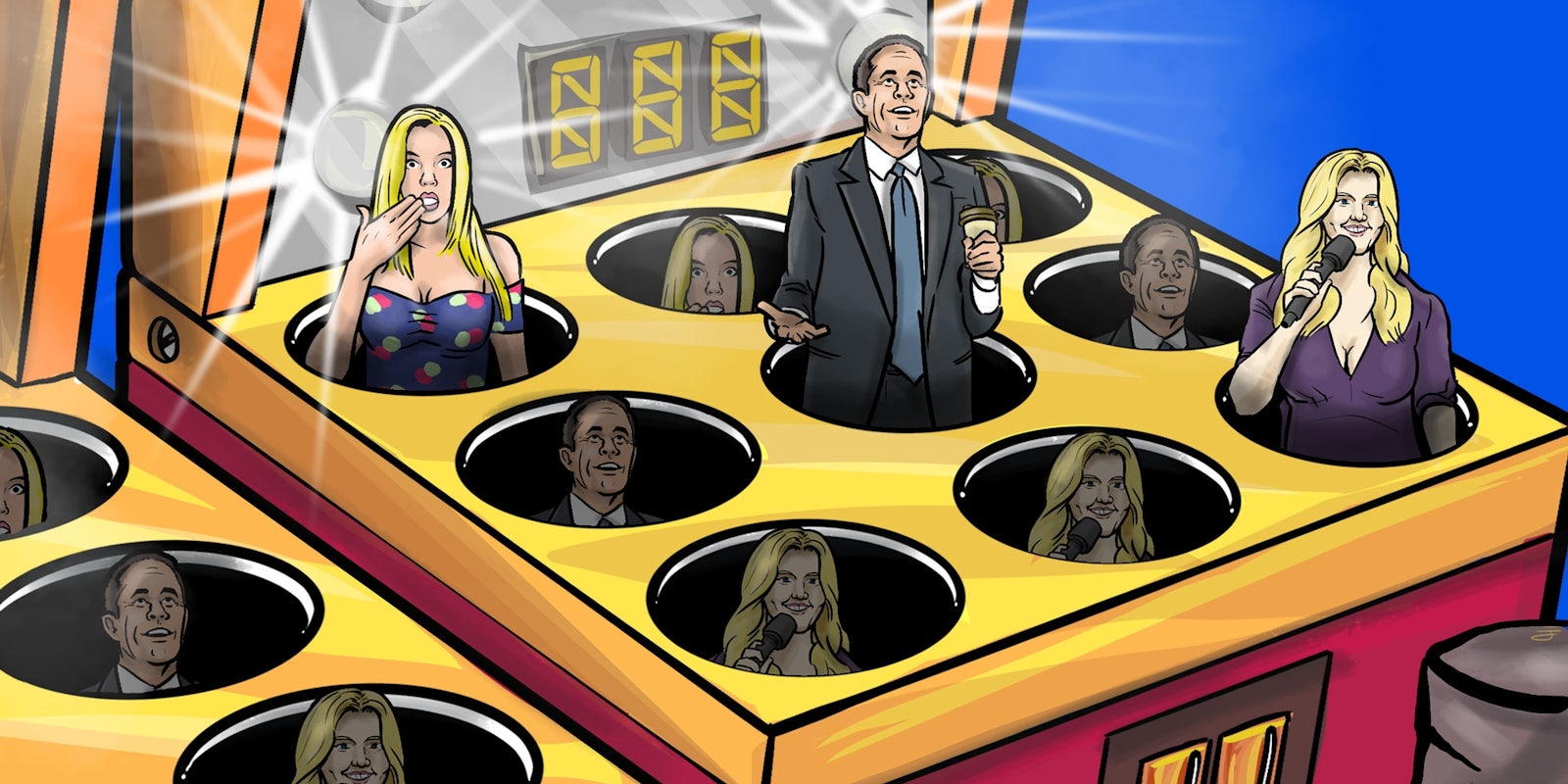

Could we take a joke this year? Did we even want to? Indeed, in 2015, telling a joke online often looked like this:

It was a year of debate over what’s funny, what’s not, and who exactly holds sway—and power. Over the summer, Jerry Seinfeld told ESPN’s Colin Cowherd how he’s had it up to here with the kids and their PC viewpoints, even going as far as to call out his own daughter for being too PC.

“They just want to use these words,” he said. “That’s racist, that’s sexist. That’s prejudiced.” Other male comedians like Chris Rock, Colin Quinn, Artie Lange, and Dennis Miller echoed his lament about the encroaching specter of political correctness on comedy, a medium that has favored men for decades. Writing for the Guardian, Lindy West explained that while Seinfeld hasn’t exactly been inclusive in his comedic career, young people might not be the problem. Instead, this is a chance to shift tides:

“It’s so-called political correctness that gave me the courage and the vocabulary to demand better … from the community I love. Yes, this cultural evolution is bumpy, but what Seinfeld and some other comedians see as a threat, I see as doors being thrown open to more and more voices.”

A look back at some of the years highs and lows in the comedy scene suggests that’s true, at least in part: More diverse voices are making waves, but the Internet has scaled up its outrage to match.

In March, Trevor Noah’s old tweets put the Internet on the defensive, after it was revealed he once tweeted some unfortunate things about women and Jewish people. But he’s now settled comfortably into his role as the new host of The Daily Show, and people have mostly forgotten about it. On Hulu’s Difficult People, Julie Klausner’s character tweets a joke about Blue Ivy and R. Kelly that caused the offended to call for the show to be canceled—a broad stroke for a show that is literally about terrible people and a joke that was perhaps an unintentional meta-critique of the Internet’s habit of piling on.

Netflix’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt was put under the microscope after Jane Krakowski’s character was revealed to have Native American parents, something she hid from people to appear more white and successful. In a recent interview, co-creator Tina Fey suggested this advice: “Steer clear of the Internet and you’ll live forever.”

“We did an Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt episode and the Internet was in a whirlwind, calling it ‘racist,’ but my new goal is not to explain jokes,” she said. “I feel like we put so much effort into writing and crafting everything, they need to speak for themselves. There’s a real culture of demanding apologies, and I’m opting out of that.”

Which leads us to YouTuber Nicole Arbour, whose “Dear Fat People” video showed the comedian calling out overweight people, but not really offering any insightful commentary about weight loss or body positivity that would elicit a laugh. She later presented it as “satire,” the go-to for people who often don’t know what that word means. In a rare instance where a comedian’s shitty joke saw real-life consequences, Arbour allegedly lost a movie role, but she continues to post videos with titles like “Most Offensive Video EVER.”

In an interview with Vice, author Kliph Nesteroff pointed out how comedians who court backlash often have so many more options in 2015:

“Nobody is being blacklisted in comedy. Show business is so atomized that even if you were blacklisted, say, from the major networks, there’s enough comedy fans who aren’t watching the major networks that you can still find your audience with your podcast or your YouTube channel or whatever. So even if somebody’s platform is being violated, they can easily find another platform and their audience will follow them.”

This season, South Park picked up the PC thread and created an entire recurring storyline around a new character, PC Principal, who is brought in to help with cyberbullying, microaggressions, and hate speech at South Park Elementary. But when he and his literal frat bros are presented with their own biases by a student, it’s a perfect mirror of the Internet. In one of the season’s best episodes, “Safe Space,” Butters is asked to monitor the social media accounts of the town’s residents (and some celebrities) so they only see the positive comments. This is a Sisyphean task, of course, and it nearly kills him.

When outrage is a click away, it can be a thrill to dive into the maw. But these moments of outrage are often short-lived. On the Internet, a mob can quickly form to intimidate someone into deleting a joke or apologizing for some perceived offense. But then we move on just as quickly, the outrage now just a dimly lit figure in our rearview.

These debates over political correctness and boundary-pushing in comedy have been happening for decades, of course, but now, the Internet is our mirror, reflecting a new generational divide. For younger comedians like Elliott Morgan, who just debuted his standup special Premature on Vimeo, platforms like YouTube (which Seinfeld once called a “giant garbage can”) have prepared him for PC conversations. Still, he doesn’t believe it makes things better. Writing for the Interrobang, he said:

“A constant, totalitarian approach to language causes more oversimplifications. Political correctness does not protect groups from socially ingrained stereotypes; it defines them by them. It locks those stereotypes away. It sweeps them under the rug and pretends they don’t exist. If you do that for long enough, you do not end up with a more inclusive world. You end up with an inauthentic one, where our beautiful differences are reduced to unspeakable taboos, and where Donald Trump and his hair are actual contenders for the White House.”

When Daily Dot contributor Cece Lederer taught a standup class at a college this summer, she saw firsthand how young people often had to work through ingrained ideas of political correctness to find humor in a story or joke:

“They were downright petrified of being offensive, especially when it came to talking about gender, sexuality, and dating. And I was surprised to find that a white male was most worried about potentially offending his audience.”

When outrage is a click away, it can be a thrill to dive into the maw.

In 2015, Amy Schumer drew perhaps the most high-profile backlash over jokes, after people zeroed in on a sentence in a mostly positive Guardian piece, in which the author lamented that Schumer has a “shockingly large blind spot around race.” It’s a fair criticism, one that should have opened up a more important conversation about power, race, and accountability. But, because the Internet loves to measure people, critics attempted to suss out if Schumer was feminist enough. Ironically, this paralleled an episode in season 3 of Inside Amy Schumer, in which 12 men judge whether she’s hot enough for TV: another mirror for the Internet.

In the wake of the backlash, people pointed out that there’s Amy Schumer the real person and there’s the “character” of Amy, who often is oblivious to the issue of race or bumbles through her privilege—a depiction many white people might be able to uncomfortably relate to. After the release of Trainwreck this summer, the Atlantic’s Megan Garber called it the rise of “ladyjerk” (much like Klausner’s Difficult People character): “The movie is, by way of its star and its plot, giving a woman permission to do something that many a movie-dude has done before, by default: be a jerk, and be loved anyway.” (This was also a year in which comedian and Inside Amy Schumer writer Kurt Metzger was called out once again for harassing women online, though he only saw a fraction of the blowback that she did. Ironically, he’s listed as a writer on the “12 Angry Men” episode.)

Even Sarah Silverman, never one to tone down her jokes, has said that maybe it’s good to be politically correct and listen to what younger kids are saying, instead of dismissing them. Comedy, in its essence, elicits a physical or emotional response. Maybe it’s a laugh, maybe it’s a heavy sigh, but it’s a reaction. A good joke, especially one about a taboo subject, offers a bigger truth or insight. But comedians have to try them out to know whether to discard or move forward with it: This urge to embrace inclusivity and more voices is weeding out the old men yelling at clouds. Comedians (like Seinfeld) must evolve with their audience or die.

Illustration by J. Longo