BY TED COX

I don’t remember exactly when I felt his erection pressing into my back. It might have been while he whispered in my ear, “Long ago, you were the Golden Child. But, somehow, that Golden Child was hurt, and you put up a wall to protect yourself.” Or it might have been when other men in the room broke out in song:

How could anyone ever tell you/

That you’re anything less than beautiful?/

How could anyone ever tell you/

That you’re less than whole?

I sat on the floor between the outstretched legs of a camp guide, my head leaning back against his shoulder. The guide sat behind me, his arms wrapped around my chest. This hold was called “The Motorcycle.” Five men surrounded the two of us, their hands resting gently on my arms, legs and chest.

There were about ten other groups like this sitting on the floor in the darkened room: one guide giving “healing-touch therapy” while the surrounding men rested their hands on the receiver. Some men were held in the Motorcycle position. Others were turned towards their guide, cradled the way a parent would hold a sobbing child who had just scraped her knee on the sidewalk.

In one corner of the room, a portable stereo played Shaina Noll’s song. At one point, the staff members all sang out in unison, their voices filling the high walls of the camp lodge. Somewhere in the room, a man sobbed over the sound of the music.

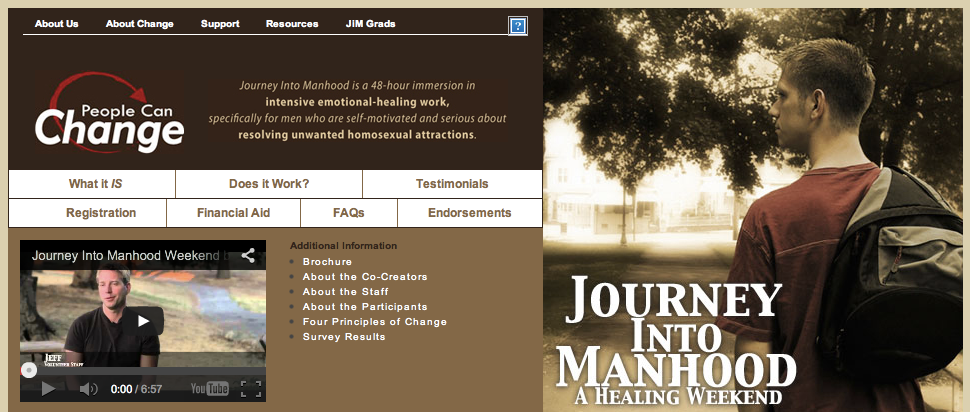

It was the first night of “Journey into Manhood,” a 48-hour weekend retreat designed to help gay men become straight. In that room, about fifty men—some thirty “Journeyers” and fifteen staff members—sat on the carpeted floor of a ranch lodge two hours outside of Phoenix, Arizona. Most of the men, except for a few of the staff members, struggled to overcome their attraction to other men.

Sometime during all that holding and touching and singing, while I was cradled in the Motorcycle position, I felt it: the unmistakable bulge pressing through his tight jeans. It was the first time in my life I had a felt another man’s erection.

What the staff members and other Journeyers didn’t know was that I was attending the weekend undercover. I’m straight. I’m also an atheist. By that February evening, I had been undercover in the so-called “ex-gay” movement for just over a year. Before signing up for the $650 JiM weekend, I had attended weekly support-group meetings and weekend conferences geared towards Christian men and women desperately trying to overcome their same-sex attractions. I am currently writing a book about my experiences posing as a same-sex attracted Christian man—“SSA man,” in the lingo.

My motivation for undertaking this wild project stems from several factors. First, I was raised in the Mormon church, which has taken the lead against equal marriage rights for gays and lesbians. It’s been ten years since I left Mormonism, and I feel a particular need to stand up against the church’s well-funded opposition to marriage equality. (I wonder what Mormonism’s polygamous founder, Joseph Smith, Jr., and his successor, Brigham Young, would say about the “Marriage = 1 Man + 1 Woman” bumper stickers slapped on so many Mormon minivans.)

Second, while the ex-gay movement has publicly declared that they can bring “freedom from homosexuality,” there’s no evidence that someone can change his or her orientation through these religiously motivated programs. Rather than turning straight, the men and women that I met throughout this project dealt with a cycle of repression, backsliding into sin, then shame, guilt, and repentance. These programs collect hundreds of thousands of dollars each year on a promise they can’t deliver.

Third, these programs are dangerous. Ex-gay watchdog groups document the stories of men who, after years of failed attempts to become straight, resort to suicide. Later I’ll introduce you to Eric, a fellow JiM attendee who would hook up with men on Craigslist and then go home to his unsuspecting wife. For many men in ex-gay programs, often their wives, friends, family, and church members have no idea they struggle with SSA.

What I saw and experienced at JiM both enraged and disturbed me. I had trouble staying in character as I watched one man, as part of his therapy, act out beating his father to death with a baseball bat—just one of several “Are you kidding?” moments. How anyone could believe that a JiM weekend could turn a man straight still baffles me.

To be fair, I had several positive experiences that weekend. I saw several men, some for the first time in their lives, lose the anxiety they feel about their sexual orientation. Up until that weekend, some of them had never told anyone about their struggle with SSA. In the course of the retreat, they would relax around other men who struggled the same way they did.

***

“Journey into Manhood” co-founder and “Certified Life Coach” Rich Wyler goes to great lengths to keep his techniques hidden from public scrutiny. Only after I had booked my non-refundable flight, and paid the non-refundable retreat deposit, was I informed that all Journeyers are required to sign a confidentiality agreement. Last year, when I attempted to write an article for Salt Lake City Weekly to run the week that Journey into Manhood arrived in Salt Lake City, Wyler complained to the paper, citing the confidentiality agreement I signed.

While the article idea I pitched to SLC Weekly would discuss only publicly available information about Wyler and Journey into Manhood, SLC Weekly—citing insufficient time to run the piece past their legal department—pulled the article and interviewed me instead.

After that interview, I discussed the confidentiality agreement with attorneys, editors, journalists, and gay-rights activists. As a result of those discussions, I have decided to discuss in detail several aspects of the JiM weekend. The decision was not easy. But given what I experienced, the pain that many of these men feel, and the money that Wyler’s organization takes from them, I feel obligated to speak out.

The Friday morning of the retreat, I double-checked my bags to make sure I didn’t pack anything that might divulge my true identity or my secular tendencies. Stricken from the usual weekend-getaway packing list: My iPod, for the Rage Against the Machine and Immortal Technique albums, and my current reading list — Karen Armstrong’s The Bible: A Biography, and Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Before flying out of my hometown of Sacramento, I sent the camp location and phone number to a handful of friends. I told them that if they didn’t hear from me by Sunday night, they should contact the authorities. I did fear a bit for my safety: I worried what would happen if I was, well, outed.

The flight stopped over at LAX, where a blinking cockpit light forced passengers to switch planes. So by the time I touched down in Phoenix, I was almost an hour late. I rushed through the baggage claim looking for Robert, my carpool driver.

In the days leading up to the retreat, PCC (“People Can Change,” the sponsor) arranged for men driving from close locations or arriving at the airport at close times to ride together to camp. Since I paid almost $900 in camp fees and airfare, my wallet was happy to avoid renting a car for the weekend.

***

I’m riding with three other men. Two of them sit in those slouchy leather airport chairs. The third guy’s plane should touch down soon.

Robert is a quiet, pudgy, middle-aged man from California. He’s married with children, has attended ex-gay programs for several years, and signed up for JiM (“Journey into Manhood”) on the recommendation of one of his ministry leaders.

Dave is a young father from Texas. He’s a lifelong Mormon and works a corporate job. Before attending JiM, he took part in the “New Warrior’s Training Adventure” weekend.

Tony finally de-planes. As we climb into Robert’s rental car, Tony shares his story: He’s single, in his 30s, and hails from Texas, where he works as a biologist. He tells us that this is his second time attending JiM. I’m surprised. Doesn’t the effectiveness of the JiM weekend depend on us not knowing what happens beforehand? Isn’t that the reason we have to keep JiM techniques secret?

I prod Tony to divulge information about what to expect, but he won’t budge. Plus, he attended a few years ago, and he thinks the program may have changed since then.

As the city gives way to dry rolling desert hills, we talk about our lives.

Dave talks about life with his boys. Robert and his wife have been struggling financially, but they seem to be doing okay. Tony loves his work in the science field.

For the most part, I dodge the group’s questions. But when pressed, I try to answer their questions with as much truth as possible.

I use the same cover story since I began attending ex-gay programs: From a young age, I was attracted to other guys (false); I was raised in the Mormon church (true), and served a mission (true); I married in my early 20s (true), but the marriage fell apart (true) after I fell in love with my best friend, Brian (false). After my younger brother’s suicide in 2003 (true), I reevaluated my life (true) and had a religious reconversion (false). I recently joined ex-gay ministries in 2007 (true), even though I still haven’t found a new faith (false).

Yes, I’m lying to them. And I feel horrible for it. It doesn’t help that from our long conversation during the ride to camp, I learn that these guys are good men, the kind of people you hope to have as neighbors.

***

After an hour in the car and a late lunch stop at In-N-Out (sorry, East Coast readers, but you haven’t eaten a real burger until you’ve scarfed an In-N-Out Double-Double), we finally turn off the Interstate and onto a windy dirt road. The mood in the car grows tense with anticipation as we travel the last few twisty miles to the white ranch gates. Outside the window, the desert stretches out in all directions. We’re in the middle of nowhere.

As Robert pulls the car into the dirt parking lot, I panic: What happens if my cover is blown? Or if I decide I want to leave the weekend early? The carpool saved me some cash, but on the other hand, I can’t really leave unless Robert drives me out. Or would I have to walk the dusty dirt road to the highway? And then what? Hitchhike back to the airport?

It feels like no matter what happens, I’m stuck here for the weekend.

Robert shuts off the engine. Per the instructions PCC emailed us before the weekend, I collect everyone’s cellphones and close them up in the glove compartment. There will be no contact with the outside world until Sunday afternoon.

The four of us step out of the car and pull our bags out of the trunk.

Things get real weird real fast.

After check-in, a staffer asks me to follow him. We circle around the back of a cabin. He motions me toward a man standing fifty feet away, dressed in all black and grasping a gnarled wooden staff. I slowly walk towards the man in black.

I stop a couple of feet away from him. He eyeballs me, shows no emotion, and stays silent for several uncomfortable moments.

Finally, he takes in a deep breath and asks, “What is a man?”

I don’t remember my answer. In fact, I don’t remember if that’s the exact question he asked, because once I muster some half-assed answer, he points to another man several feet behind him, also dressed in black and holding a staff, and sends me on my way.

There are about five of these men, standing fifty feet away from each other in a long curved line, leading from the registration cabin toward a large lodge.

Each staff man follows the act of the first. They say nothing for a few seconds. Once I’m feeling completely awkward, the question comes, open-ended and something to do with men or masculinity, or my reason for attending: What makes a man? How do you know you’re a man? Why are you here?

After the second man, I flash back to Monty Python and the Holy Grail and suddenly feel like King Arthur answering the bridgekeeper’s questions: “What is your name? What is your quest?” An uncontrollable smile creeps across my face.

Once I answer the last man’s question, I’m directed to enter the lodge. It’s a wooden structure that looks exactly like you’d expect an outdoorsy camp lodge to look: spacious main hall, high ceiling, large stone fireplace. Inside, metal folding chairs sit in a circle. They’re half-filled with Journeyers who entered before me. On the floor in the middle of the circle, a single candle burns on top of a square rug. Native American flute music plays. Every few minutes, another Journeyer enters the room, looks around, and takes a seat in an empty chair.

After a brief welcome from yet another staff member — I count around fifteen total — and the first of many reminders about our signed confidentiality agreements, we’re briefly introduced to the staff.

There are two levels of staffing at JiM. “Guides” are men who lead the exercises and take a major part in the instruction. Guides have more experience with the JiM program. Many of them struggle with SSA (“same-sex attraction”), some do not. “Men of Service” have less or no experience at a previous JiM weekend, and are there to assist the Guides.

PCC made it clear before the weekend that JiM staff “are not professional therapists or counselors, or are not working as professional therapists or counselors in the course of the weekend.”

Early in the evening, staff members reenact the classic children’s tale, “Jack and the Beanstalk,” with different staff members playing the different roles.

The story, a narrator explains, is loaded with coming-of-age? symbolism. Fatherless Jack has lived in the safe, feminine world under his mother’s care; the old man in the village represents ancient tribal elders who help boys transition into manhood; the seeds given to Jack represent both his sperm and the masculine potential for creation. Like most women, Jack’s mother doesn’t understand the importance of the seeds, so she chucks them out the window. The reenactment ends with Jack sent to bed without supper. After all, he screwed up his masculine duty to provide food for his family.

Much like Jack’s adventure, “Journey into Manhood” is the initiation into the mysterious world of heterosexual masculinity that has supposedly eluded us for so long. But as I look at the men filling in seats around the lodge room, especially the men who appear to be in their late 50s, I wonder: Have they never felt like men?

***

We waste no time jumping into the exercises.

First, we stand up and form two parallel lines. We stand with our lines facing each other, each man mere inches away from the man in front of him. I’m staring at a blond guy barely into his 20s.

A voice from somewhere in the lodge barks instructions to us: “What stories do you tell yourself about this man?”

I want to participate in the retreat exercises as fully as possible, so I follow the instructions and, just by his appearance, try to piece together this man’s story.

He’s dressed like he looted an Old Navy store. Short, spiky, blond hair. Clean-shaven. I guess that he’s a college student.

Then, after several awkward moments, a staffer bangs a drum. At that signal, every man in the room takes one step to the left. If you were to look down on us from above, the two lines would rotate like a bicycle chain.

Now I’m facing another man in front of me; this time he appears in his late 30s. The voice booms through the lodge: “Look into his heart.”

The drums echo again, and I take another step to the left.

I can never know what it’s like for these men, trying desperately to change their orientation. But to try to see it from their perspective, I imagine the exercise as if I was staring into the eyes of a woman mere inches away. The only time I’ve stared someone in the face like this is at the end of a really good first date. You know: the shaky, heart-thumping moments spent mustering the courage to go in for a first kiss.

In another exercise, one Journeyer stands at the center of the room while a Guide asks other Journeyers to raise their hands and give examples of mental blocks or excuses that keep us from effecting real change away from homosexuality. After each man gives an example—“rationalization,” “justification,” “intellectualizing”—he stands up and presses against the other standing in the middle of the room. Soon it’s a mass of male bodies smushed together.

***

In one of the final exercises for the night, we form another circle in the middle of the room. (We end up doing this circle thing a lot.) Staff members pass out black cloth blindfolds, which we tie around our eyes. With the blindfolds in place, staff men squeak their sneakers and bounce basketballs on the hard floor, recreating the sounds from a busy high-school gym class.

They yell out the the kind of shit-talk typical of high-school kids:

“C’mon, take the shot!”

“You suck!”

“How did you miss that?”

“Why are you always picked last?”

“Okay, let’s hit the showers.”

When we remove our blindfolds, I see that many of the Journeyers are shaken up. The exercise has awoken some terrible adolescent memories. With tears streaming down some of our faces, we follow staff members into an adjoining, smaller, carpeted room. We sit in a large circle along the edges of the wall.

“For this next exercise,” says one of the staff, “Try to keep an open mind.”

Three staff members take a seat in the middle of the room. They demonstrate three different “healing touch” techniques.

First: Side-by-side, where two men sit shoulder-to-shoulder, facing the same direction, their legs outstretched in front of them. The man giving the Healing Touch puts one arm around the receiver.

Second: The Cohen Hold, named after “certified sexual re-orientation coach” and Healing Touch pioneer Richard Cohen. For this position, the receiver sits between the legs of the giver, their chests perpendicular, the receiver’s head resting on the giver’s shoulder. The giver encircles his arms around the receiver.

Third: The Motorcycle. The receiver again sits between the legs of the giver; this time, the receiver leans his back up against the chest of the giver. Again, the giver wraps his arms around the receiver.

The idea behind Healing Touch is to recreate the father-son bond that apparently we missed as children. In this twisted, neo-Freudian

theory on the cause of homosexuality, men who didn’t get appropriate touch from their fathers sexualize their need for a “healthy” non-sexual masculine connection. Healing Touch techniques recreate a loving, father-son bond, and are completely non-sexual.

Well, that’s what they tell us.

***

Staff divide us up into groups of six or seven men, about two staff members and four Journeyers per group.

With the groups spread out around the floor of the darkened room, one Guide in our group—a thin man in his early 50s with short dark hair and thin metal-frame glasses—asks who wants to go first. Nobody speaks up for several moments.

Since I started this entire undercover project, literally thousands of times I have asked myself: Why? Could it be that I’m a deeply closeted gay man? Is it because I’m pissed off at the religious right, and I want to do everything in my power to bring it down? Or is it an unbalanced addiction to seeking out the strange and unusual this world has to offer? Or something else?

These questions again run through my head as I reluctantly raise my hand.

The Guide asks which hold I want. I pick the Motorcycle. I’ve come this far; might as well go all the way.

The Guide leans back and opens up his legs. I scoot between his thighs, turn away from his face, and lean back while he wraps his arms around me. I flash back to a night months before, when a then-girlfriend held me the same way. She lit candles. We drank wine and later had sex.

At the Guide’s direction, the other men from the group place their hands on my arms, legs, and chest. This is so they can impart their healing masculine energy to me.

Then the music starts.

How could anyone ever tell you/

That you’re anything less than beautiful?/

How could anyone ever tell you/

That you’re less than whole?

The Guide whispers in my ear how I used to be the Golden Child, how everything was wonderful before someone hurt me, how I put up walls to protect myself, and now it was time for those walls to come down.

Like so many times that night, I’m trying not to crack up. To use another children’s tale, I feel like the little kid in “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Except this time, instead of pointing out that the emperor is parading down the street in his birthday suit, I want to stand up and scream, “Are you fucking kidding?”

One-by-one, the “Journeyers” (as participants are called) in our small group take turns reenacting painful childhood memories. Jason, a baby-faced, barely-out-of-college guy, struggles for a minute to come up with something. Then, finally, he half-heartedly recounts the time he tried to get his dad’s attention. But Dad rebuffed him, saying that he was busy reading the newspaper.

“So what message did you internalize from your dad that day?” prods the “Guide,” a staff member.

Again, Jason struggles. “That he wanted to read the paper?” We chuckle.

The Guide fills in the blanks. “He was telling you that the newspaper was more important than his son.”

The Guide instructs Jason to reconstruct the scene. Jason picks men from our group to play his young self and his dad. Dad grabs a scrap of paper sitting in the sunny cabin, takes a seat in one of the folding metal chairs, and buries his face in the paper. Young Jason approaches Dad, trying to get him to play. Dad brushes him off: “I’m busy.”

Young Jason and Dad play out the scene over and over again, while the Guide and Jason stand off to the side.

“You were a boy who needed his father’s attention. And do you know what you got instead?” asks the Guide. “He told you you were worthless. He didn’t have time for you.”

Dad picks up on the Guide’s words and incorporates them into the dialogue. “I don’t have time for you. You’re worthless. Leave me alone.” For the fifteenth time, young Jason approaches Dad seated in his cold metal chair, and Dad rejects him. Young Jason skulks away.

Much like Jason had trouble coming up with a traumatic memory, he draws a blank when the Guide asks him what he can do to change the situation. Each Journeyer, after recreating his memory, must step into the role of his younger self and take control to change the memory.

***

This final step is vital to the process, and it varies based on the memory. When Charles, a young evangelical minister from Oregon, recreated the day his father beat his mother because she wanted to buy Charles designer jeans, the Guide told Charles that to take control of his memory he had to remove his abusive father. What ensued was a four-minute wrestling match, where Charles struggled to drag the Guide out the cabin and slam the door shut.

With few exceptions, most Journeyers took control of their memories the same way. Whether one of the three Guides played a father sneering about the “faggot” behind a fast-food counter or the high school locker-room bully, Journeyers dragged the offending character out of the cabin and slammed the door shut.

The Guides put up a good fight. When Charles the minister didn’t completely close the door to the cabin, the Guide pushed his way back in. “Are you kidding me?” panted Charles when he was told he had to start all over again.

My resolution was different. I recounted the time in fifth grade my father stormed into my bedroom when he heard me fighting with my little brother, punched us to the ground, then walked out. I played the part of my younger self. While I lay on the floor of the cabin, the Journeyer playing my brother lying two feet away, the Guide pulled out a blanket and draped it over me.

“You never got up from the bedroom floor, did you?” he asked. “You’ve been lying there all your life.”

He had the other men in the room kneel around me, their knees pinning the blanket so that I was wrapped tight like a taquito. Only my head poked out from an opening.

My resolution was to finally, for the first time in my life, get up from the floor where my father had left me physically and emotionally bruised all those years ago. On the Guide’s mark, I struggled to push myself up, but the weight of the men kept me pinned. Sweaty and exhausted after several futile minutes, I switched strategies: Wriggling like a worm out of an apple, I freed myself out of the topside of the blanket. My shoes were pulled off in the effort. I think my feet stank.

But for Jason and his newspaper-reading father, the solution took a violent approach. First, the Guide playing Jason’s father rises from the metal chair to stand in front of him, repeating the lines about Jason being worthless. Next, Jason is handed a baseball bat and told to kneel on the floor. A punching bag is placed between him and the father.

“What you need is a new father,” the Guide says, moving another Guide to stand behind the first. “But this old father is standing in your way. You need to get rid of him.”

Jason looks wide-eyed at the man standing in front of him. The Guide who has been leading Jason through the exercise makes an over-the-head swinging motion. Jason grips the bat, lifts it up behind his head, and swings it down, the bat thudding on the punching bag.

“Again!” yells the Guide.

Jason obeys. He swings over and over again.

“Yell! Let it out!” commands the Guide.

His yells are weak at first, but with each swing, they grow deep and primal. Every few swings, Jason’s old father buckles a little, clutching his body as though wounded.

Another Guide motions for the rest of us to encourage Jason.

“Yeah, man!”

“Do it!”

“C’mon!”

I’m horrified by what I see—Jason beating his dad to death in effigy—but I join in the growing roar of voices. Jason seems like such a nice kid, the kind of guy whose biggest regret was the day he forgot to do his algebra homework.

After several minutes, Old Father crouches close to the floor. Jason wails away, his timidness fleeing with his wide-eyed, belly-deep screams.

“Finish him!” commands the Guide. A few more swings, and it’s over. Old Father lies motionless on the ground.

The room is silent, except for the New Father, who stands with his arms open, repeating the lines that have been covered by the thudding and screaming: “I love you, son. I care about you.”

Jason drops the bat, stands, and approaches New Father, who wraps his arms around his son.

Many of the other scenarios end the same way: the Journeyer is held by the Guide playing his father, who tells him how much he loves his son. I’ll admit feeling a twinge every time I see it. What son doesn’t crave his father’s love?

***

After our group has finished the exercises, we walk from our cabin to the carpeted lodge room. Inside, the lights are low. While the different cabins slowly file in, two staff members off to the side of the room sit in the Motorcycle position. The man in back gives the other a back rub.

Once all the men have assembled, a Guide speaks briefly about the work we did with our father issues. He then instructs us to take out our pens and notebooks. We are instructed to write the letter that we wish our ideal father, the Golden Father, would write to us. After a few minutes, Guides take their places for another holding session. When my turn comes, I opt for the side-by-side hold. I don’t need to feel another erection in my back.

While the Guide reads me my letter, I think about the beatings and bruises and black eyes my dad gave my brother and me. Mom was the breadwinner most of my childhood years; I think Dad took out on us his frustration over feeling emasculated. In the patriarchal Mormon faith, a stay-at-home dad never fully lives up to his manly obligations. Dad and I haven’t spoken much in the ten years since I left the Mormon church; in fact, I haven’t heard from him at all in three years. And yet, despite being raised by an abusive, spiritually castrated father, I have a strong preference for women.

When each man has been held, we adjourn to our cabins.

Just a few hours left. I want to go home.

My carpool piles into our vehicle and we cruise away down the road that, thanks to the rain, is slowly turning into slop. I turn on my cellphone, and as soon as I can get a signal, text friends and family that I am alive, safe, and headed for the airport.

“How was it?” they ask. The medium limits me to 140-character messages. I really don’t know how to respond.

I should be asking the guys in my carpool what they thought of the weekend. I should be asking them what they experienced, and how it affected them. But I’m too tired to think about that. I haven’t slept in two days.

What am I supposed to do with this experience? I signed a confidentiality agreement before participating, but how can anyone keep quiet about something this intense? How can I not tell my friends or family members what I saw or did? And what about the married men? How could they not tell their wives what they were doing all weekend?

I turn around to ask Tony, the guy who had attended “Journey into Manhood” years earlier, how the weekend was different this time around. He says that it was “pretty much” the same as he remembered, just a couple of minor differences.

Is the confidentiality agreement really about making the weekend more effective for Journeyers? I doubt it. Included in the information packet is a page urging us to return for a second or third weekend. “Sometimes a price discount is available for men who are going through the JiM weekend a second time,” reads the flier.

We stop for dinner at the In-N-Out. Dave notices that I’ve become withdrawn from the conversation as I try to answer the barrage of text messages from my friends.

“I’m just tired, you know?” I respond.

“Yeah, man, me too.” He smiles and puts an arm around me as we walk back out the car for the final leg toward the airport.

And then there’s Dave. We have become friends during the weekend. I’m feeling guilty for lying to him, for betraying his trust.

At the curb of the terminal, I grab my bags and hug the guys. I worry about them and what will happen when they return home. If they’re hoping they’ll end up straight, I can’t help but think they’re in for a major disappointment.

Finally back in Sacramento, my friend Pauline, the self-described fag hag, picks me up from the airport and drives me to her favorite bar.

I spill my guts over a much-needed beer. “Oh my God,” she says, over and over again between drags on her cigarette.

My phone buzzes. Looking at the caller ID, I sigh, tell my friend it’s the call I’m expecting, and walk outside the coffee shop.

It’s Dave. I’m not looking forward to this.

***

A week has passed since returning home from JiM. Several Journeyers have tried contacting me in the days since. Before leaving the retreat, staffers handed out thick packets of information, which besides promoting two more of JiM co-founder Rich Wyler’s retreats and his telephone coaching service, urged us Journeyers to keep in touch with each other. There was also a check-in conference call, and an invitation to join a Yahoo! group. I decided not to participate in either of those. I felt like I had intruded enough into their lives.

I had also ignored all the calls and emails from the other Journeyers. Most of the men stopped after the first few tries. Dave, however, didn’t give up.

He eventually emailed me: “Dude, I miss you… I hope you’re doing well. I called you a couple of times. If I’m harassing you just let me know.”

I wrote back: “I’m okay. I miss you, too. The thing is, I have something to tell you, and you’re probably not going to like it. We should talk over the phone.”

So now Dave was calling me, and this time I answered.

While pacing back and forth on the shop sidewalk, I tell Dave everything: how I’m a straight writer, how I was at JiM undercover.

“I knew it!” he says. “I knew something was off!” Apparently my explanation at JiM about my faith proved less than convincing. It seems, though, that Dave was suspicious of my religion, not my sexual orientation.

But that doesn’t matter now: Dave is upset. He has every right to be.

“This is why I have this issue!” he groans. “I’ve had trouble trusting men. Now here we go again!”

I may have lied about my involvement, but I wasn’t about to let him pin his issues on me. I go on the attack.

“C’mon, do you really think straight men go off into the woods and hold each other?” I demand. “What about that all-night holding session you told me about? Does that sound like something straight guys do?”

Surely he would see the absurdity of it all.

Silence on his end for a moment. Then, quietly: “I don’t know, man. I don’t know.”

We end the call, and I walk back inside. I’m worried about how this will affect Dave. Dave is a stable guy, but what if word spreads among the Journeyers? How will they take it?

Dave calls back after a couple of hours. He is more composed, but he wants to know more about my motivation, about my stance on homosexuality.

I tell him that I think he’s normal, and that professional, reputable psychological organizations agree. I tell him that biologists have observed homosexual behavior in hundreds of species. I doubt I get through to him. How much does science really matter when God has spoken?

And there’s more to consider than just Dave’s feelings. “What do you want me to do?” he asks. “Leave my wife? Leave my kids? Just go live with some guy?”

There’s no easy choice for Dave. Either way, he loses something. Leaving a religious philosophy like Mormonism isn’t as simple as changing underwear brands. Often your friends stop calling, and your family members stop inviting you to dinner. Sure, Dave could finally live out and proud, but at what cost?

“I don’t know, man,” was all I could say. “I don’t know.”

Ted Cox hates bad beer and writing bios in the third-person. Follow his writing and speaking gigs on iheartcox.com.This article was originally featured on AlterNet and The Good Men Project and republished with permission.