According to Social Security, 6.5 million people in the United States are alive and kicking at 112. Before you leap to applaud modern medical advances, though, even the agency admits that most of these people have probably gone gently into that good night.

However, it hasn’t been able to formally determine that, because it can’t access death certificates for them, as many aren’t digitized. The agency is pleading for better vital records systems to connect its records to birth and death data across the United States, but the government needs more than that: It needs a comprehensive tech overhaul that extends far beyond who’s living and dying in America.

In the case of the Social Security problem, the implications are obvious. Social Security fraud is a significant issue, and having large quantities of Social Security numbers floating around for the taking means that people can establish lines of credit, mortgages, car loans, and credit cards in the name of people long dead. There’s no one for financial institutions to go after once those borrowers become delinquent. Poor vital records also make it difficult to compile accurate demographic statistics on the United States; for example, having data on how many people are actually alive at 112 would be genuinely interesting.

As a short-term solution, the government could invest millions in digitizing death certificates, developing a software platform for sharing the data, and connecting it with Social Security. This, however, is a terrible idea. It’s not the best solution and it will in fact actively perpetuate the problem of hodge-podge, scrap-quilted government software; what the government really needs is substantial investment in technological infrastructure to bring itself up to date with the civilian world and with other world governments. Without that investment, Social Security and the Healthcare.gov debacle will seem like drops in the bucket.

The government needs to invest in a tech overhaul, and it needs to do it fast. When compared with other Western nations, the IT available to government employees is a joke. Peter Orszag, former director of the Office of Management and Budget at the White House, remarked several years ago: “Twenty years ago, people who came to work in the federal government had better technology at work than at home. Now that’s no longer the case.” Since then, little has changed.

Take, for example, the Patent and Trade Office, which has a byzantine processing system that requires hard copies of all applications. Despite the fact that some 80 percent of applications are filed electronically, personnel still have to print and then scan them. That’s because the agency hasn’t bothered to upgrade its infrastructure. Such outdated equipment generates a huge waste of time for employees, translating into high expenses for taxpayers, and it also makes it more difficult to cross reference and search for preexisting patents and related inventions.

In Washington state, government agencies are still using computers and software from the 1980s for vital records, managing the court system, law enforcement tasks, and handling taxes. Roughly one third of the state’s technology is over two decades old, and IT personnel need to be familiar with obsolete coding languages like COBOL in order to maintain the backends of key government sites and software.

Or take a look at emergency services and what happened when 911 systems attempted to cope with cell phones. Services equipped for landlines often didn’t know what to do with cell phones, rerouting calls endlessly or dropping them altogether. This is an illustration of outdated tech, but it’s not the end of the story: Because the tech is so outdated, there’s no actual data on how many calls were mishandled and how they were mishandled. Thus, we have no functional way of knowing exactly how badly the 911 system is failing us.

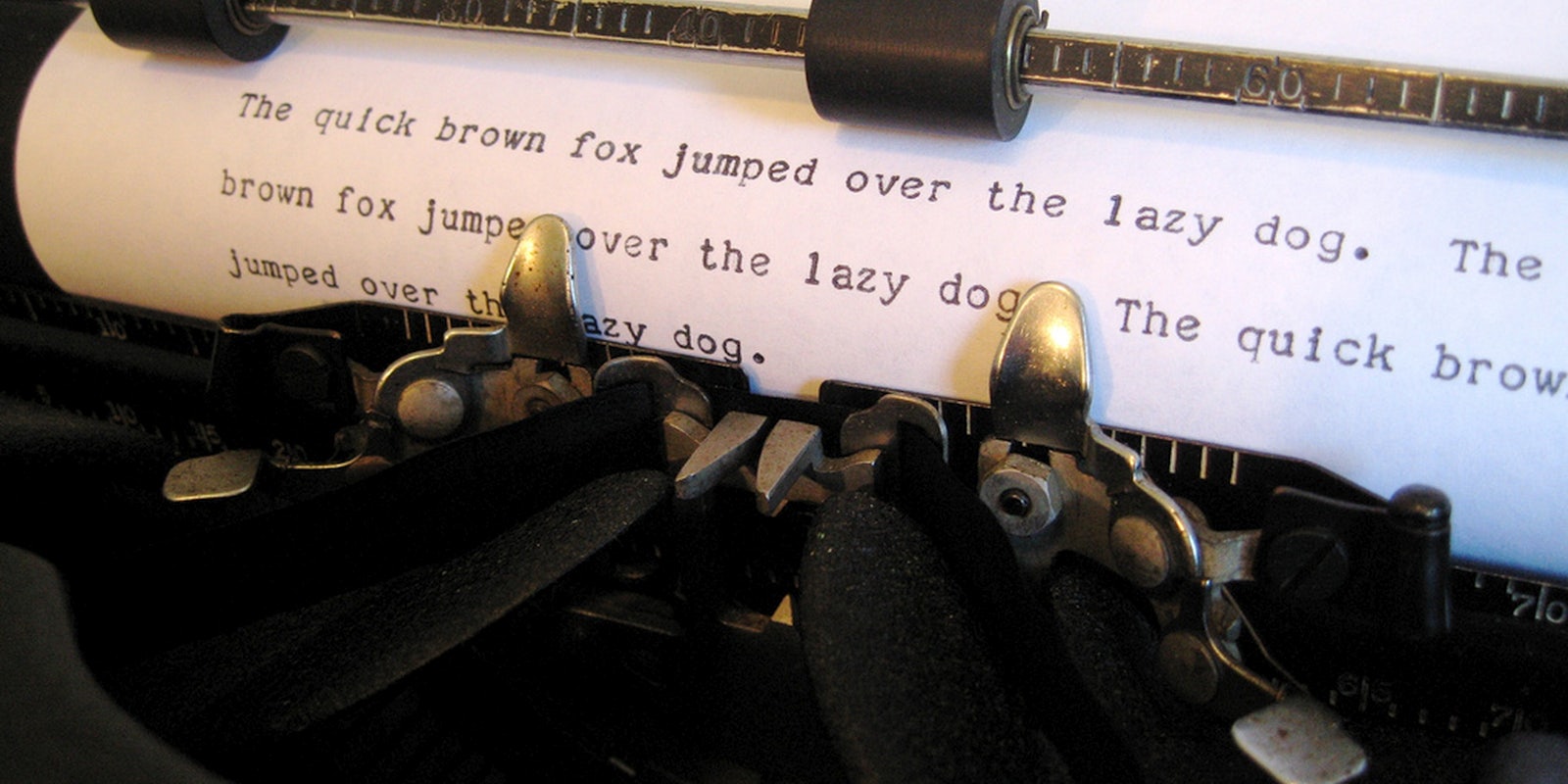

Local governments are particularly terrible offenders, with many local agencies using typewriters or even handwritten documents for a large proportion of their filing. Jersey City mayor Steve Fulop reportedly once said, “[Typewriters] are staying as long as I’m in office, I can assure you that. It’s a nice touch.”

In New York City, for example, some 18 agencies use almost 1,200 typewriters to write up reports and fill out forms. If another agency needs the information, it needs to be digitized, faxed, or transported via runner—so much for quickly and easily sharing data across agencies. The NYPD is among the agencies still relying on typewriters for some tasks. The lack of a digital footprint can make it difficult to track down accounting discrepancies, verify identities, or determine if a person of interest has other records across the city’s sprawling government agencies, among many other things.

As Laura Kusisto reports at the Wall Street Journal, while typewriters aren’t circulating in wide production like they once were, they’re still being manufactured. One of the biggest customers of typewriter, ribbon, and accessory firms is the funeral industry, which still uses typewriters for death certificates and other filings. Another big customer is the prison system. This means that even as Social Security is pushing for a turn to digitizing old records, there’s an ongoing pile-on of new paper records that need to be transferred to computer systems.

That “nice touch” costs the government millions every year in conversion of hard copies to digital formats, tracking down information that’s not available in readily accessible digital form, and missing issues like, for example, people who are still collecting Social Security checks despite the fact that they’re dead, including the handful of people allegedly alive and in their 100s who are still getting their monthly cut. The U.S. government, from the feds to local agencies, needs a unified and networked computer system with the latest technologies and room to advance, backed by agile development.

Lydia DePillis at the Washington Post puts forward the case for agile development in compelling terms. She notes that it’s less costly than the “waterfall” mode of development used at many government agencies, and also results in more nimble, effective, and applicable software products for the government. However, she argues, inability to adapt to changing technology is a major obstacle to adoption, and so is the system used for awarding federal contracts, which is where things get particularly sticky.

When it comes to any conversation about overhauling government infrastructure in the United States, it becomes impossible to avoid talking about government contracting. Currently, a very limited number of firms are able to land government contracts, in a somewhat self-perpetuating system as they lobby for legislation that will benefit them, cultivate relationships with people in position to award contracts, and establish themselves as the standard in their field. This leaves out smaller, younger, innovative companies that might have fresh approaches to development challenges—including ideas that could radically cut costs.

In a number of attempts to overhaul government IT, the results have been spectacular and very expensive flops. One culprit is a rigid approach to IT from government officials who don’t understand software development and hardware systems and thus make unreasonable demands or create moving goalposts during development. This results in painfully ballooning budgets as contractors scramble to keep up, and unfortunately, many of the people in lead positions on such projects are also not qualified to handle IT matters.

When two people who don’t know what they’re talking about attempt to communicate, it can be disastrous. On an individual level, that can result in a frustrating game of round robin. When it comes to government contracts, it can cost billions of dollars, reams of paperwork, and endless frustration for the parties involved.

In 2013, the New York Times reported on the scope of the problem, referring to tech buying as “stuck in the last century” and discussing the Obama administration’s attempt to address the issue. It seems unlikely that the president will be able to fix the government’s clogged, convoluted, and bizarre approach to IT development and acquisitions before the end of his term. That makes it all the more imperative that our next president not only understand the importance of IT, but also understand how it functions, as she (or he) will need to be able initiate a rapid push to bring the U.S. government up to pace with the rest of the world.

If the average American can download free budgeting software for her iPhone that’s more powerful and effective than that used at major government agencies, it’s safe to say that we have a problem.

Photo via Seth Morabito/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)