Nick Marino was having a difficult time selling digital copies of his webcomic, Time Log, even though the digital versions were easier to read and sharper than his print comics.

At the Small Press Expo (SPX), a comics convention in Maryland, the 30-year-old Pittsburgh artist decided to laminate a preview of each comic and hand it out with each ebook purchase. They sold much better after that.

“I talk to people from age 20 to 70 who say they still don’t understand digital comics yet,” he said. “When people buy something, they like to have a memento of that purchase.”

Marino is just one many illustrators discovering that, even as the world increasingly goes online, there’s still high demand for print products.

Founded in 1994, SPX continues to grow. This year, the the paper-based institution invited about 450 exhibitors to its sardine-packed halls. Nearly all were webcomics or artists with powerful online presences, and all had at least one printed product to sell.

In such company, Lela Graham (pictured below) was an outlier with an especially anachronistic contribution—bookbinding. The 25-year-old told me, half joking, that for all intents and purposes she’s practicing a dead art. But thanks to the Internet, she’s found a wide audience. Her Kickstarter campaign to purchase equipment to improve her bookbinding process raise nearly $1,000 over its goal. And she plans to open up a shop on Etsy, the handmade marketplace, which offers an online storefront and community for independent artists.

“I think in a day and age where everything is done online, people really cling to fetishistic physical things,” Graham posited. “My handcrafted books are intimate. They’re small, but the material gives them weight. They feel good in your hand. They have a smell.”

Graham has also collaborated with her boyfriend, cartoonist Evan Dahm, 25, on Aftermath, a handcrafted comic book. Consumers can buy the paper version for $10 or the leather version, painstakingly handbound by Graham, for $70.

“The price is a deterrent, but there are only 13,” said Graham. “If people are really interested in our work, it’s worth it for them.”

Dahm has a wide audience for his online comics, most notably Rice Boy, but he said his Web content is primarily a means to a printed end. When Graham isn’t binding them by hand, his comic books come in both paperback and hardback versions.

“For me the goal is always to have a book at the end,” Dahm said. “I put my work online solely as a way to make it popular so people will want to buy that book.”

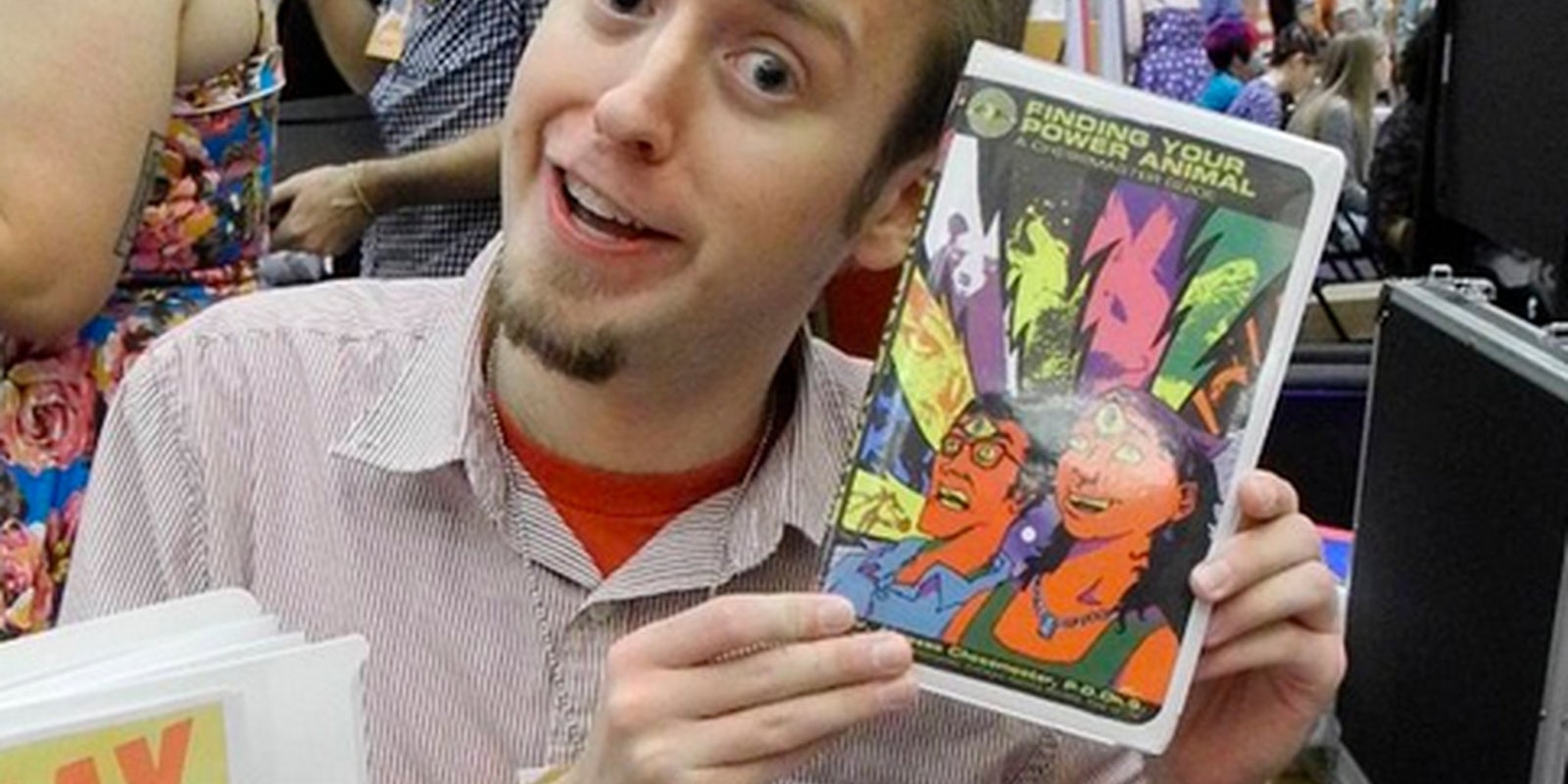

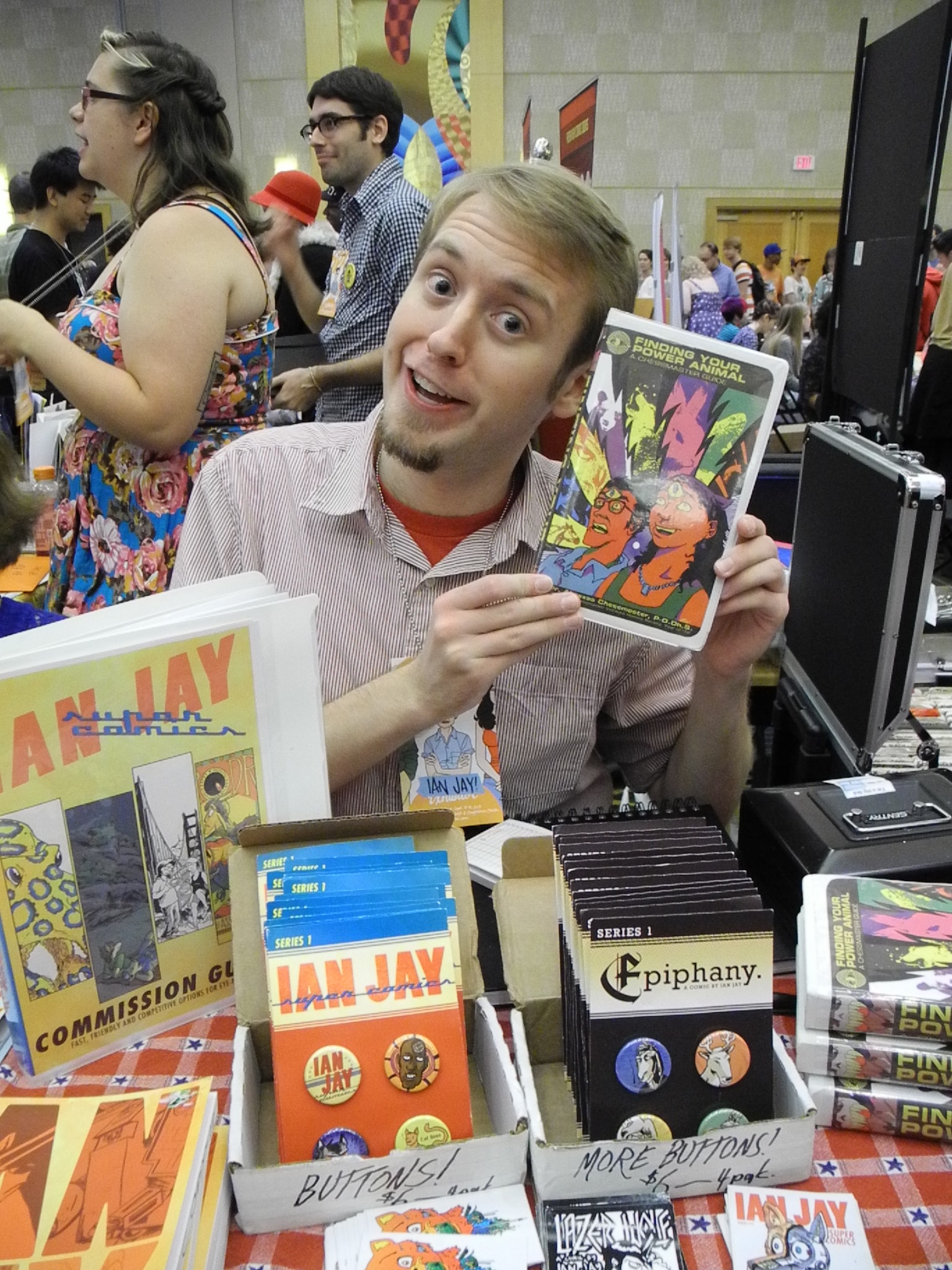

On the other end of the hall rested Ian Jay, his colorful booth littered with buttons, flyers, free zines and one comic book, Finding your Power Animal, encased in a VHS sleeve. Elbow to elbow with dozens of other Web artists, Jay clearly understood the importance of standing out.

“When you can get the content for free online, it’s not just about substance anymore,” he said. “I put a lot of effort into packaging and construction, annotation and extra perks for buyers.”

Whether comics see the Web as a means to an end, as promotion for a physical product, or somewhere in between, their presence at SPX was a statement against the idea can Internet can fully replace their printed works. They’ve put extra effort into their physical products, and it’s more valuable for it.

“SPX is doing well right now because artists are paying a lot of attention to the packaging,” Jay said. “It’s easier to support someone who’s work you like when you’re getting something more than what you can already get for free.”

Photos by Lauren Rae Orsini