When you live in a country that Transparency International ranks in the top third of most corrupt states, participating in social media requires a certain measure of trust. Case in point: When NBC’s Richard Engel arrived in Russia for the Olympics, he booted up two brand new laptops to see how long it would take hackers to get up on the systems. Within minutes, the new machines were already being probed by Olympic-themed websites, and a phishing attack followed shortly thereafter.

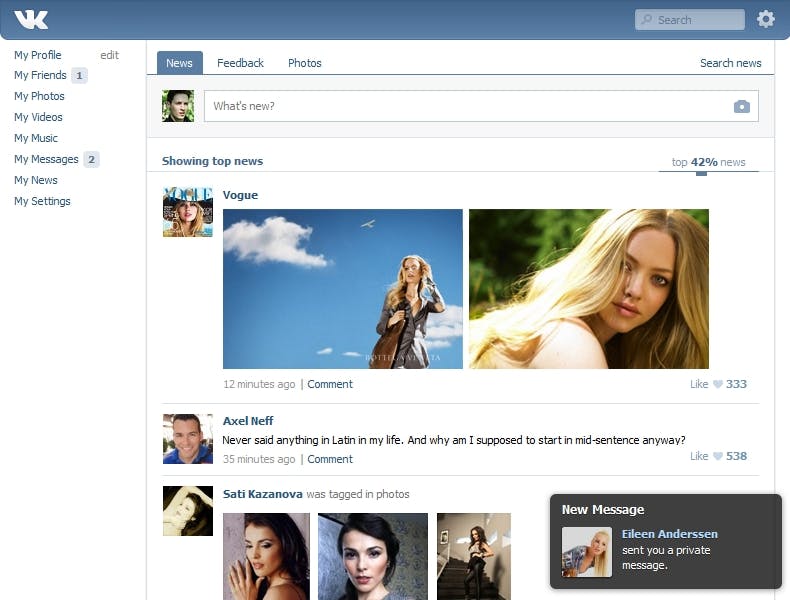

That’s a blatantly sinister breach of trust, but the more troublesome reversals are often those that look like business as usual. What’s revealed by the changing fortunes of a site like VKontakte is the role trust plays even in building digital identities in the relatively free countries of the West.

VKontakte, for the uninitiated, is Russia’s biggest social media site, making it a social force with which to contend. In 2012, when Vladimir Putin was reinstated as Russia’s president after four years as prime minister, suspicion of voter fraud drove tens of thousands to Moscow Square calling for a rerun of the election. In an effort to quell protests, Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) contacted VKontakte to request that opposition accounts be deactivated.

At the time, VKontakte was led by Pavel Durov, who had founded the company with his mathematician brother, Nikolai. As the young cofounder of Russia’s second most popular site, Durov is often compared to Mark Zuckerberg, though the positions he’s taken on privacy and free speech might make Aaron Swartz a better point of reference. Last October, for instance, he unveiled a new messaging app, Telegram, which uses end-to-end encryption so that even his servers are oblivious to their content. As a rebuke to National Security Agency opacity, he offered to hire NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden after news broke that he had fled the U.S.

It may not be entirely surprising, then, that when the FSB requested help silencing the opposition, VKontakte refused. In a state with an expansive state intelligence apparatus that’s steadily asserting its online presence, that resistance is remarkable.

It’s doubtful, though, that the company would take the same stance now. Until last month, Durov held a 12 percent stake in VKontakte, enough to keep any other investor from holding a majority of the company’s stocks. By selling his shares to Ivan Tavrin, the CEO of a Russian telecom, Durov has effectively surrendered a controlling stake to a group of businessmen with ties to Putin.

Given Russia’s reputation for corruption and government intrusiveness, it’s easy to see why that change of hands would concern VKontakte users and free speech advocates alike. Social media platforms tend to function as vast data collectors, marshaling information about a person’s group affiliations, location, and online habits into detailed profiles.

Typically, those profiles are used to build and distribute more effective advertising, or to convert a user’s pictures and text into product endorsements. The point driven home by recent reports on nature of the NSA’s PRISM program is that those same profiles can be used to create actionable intelligence for enforcing federal law. A country headed by a former intelligence agent (Putin served 16 years in the KGB before moving into politics) is that much more in need of safeguards against the steady encroachment of government surveillance.

Defenders of the intelligence community have argued that there’s nothing worrisome about that sort of Big Data initiative, provided you’ve not done anything illegal. It’s trickier defending that position when the country doing the collecting has a history of passing laws that violate international norms and discriminate against its own citizens.

Applying the methods of signals intelligence (SIGINT) to its data profiles might allow VKontakte to guess which of its users violate Russia’s recently passed antihomosexuality laws, for example. By studying the relations that make such networks social, they might be able to trace the digital links that connect journalists to their anonymous sources. At the very least, as the FSB request filed during the 2012 election shows, it could be used to stifle political opposition groups.

Such concerns may have seemed remote as long as the company’s head remained committed to transparency, both in his own country and abroad. Durov has assured customers that his role at VKontakte hasn’t changed, but with business tycoon Alisher Usmanov’s group holding 52 percent of the company’s stock, there isn’t much he could do if they decided to go over his head.

The lesson—both for Russians and for social media users west of the Urals—is that business decides who gets to use our digital identities, and business changes quickly. That’s emphasized every time the acquisition of a startup results in a change to its terms of service.

The possibility of seeing your previously sacrosanct avatar used in “sponsored posts” is the only change at stake. One indirect result of its purchase by Yahoo is that Tumblr now contributes data to one of the NSA’s most frequently requested data pools. It’s entirely likely that, as recently as a year ago, the process for handling those requests was subject to an entirely different policy, and maybe no policy at all.

That may not be as stark a difference as the one now facing users of VKontakte, but the point is the same. When it comes to our digital identities, instability is the rule rather than the exception. On a daily basis, and without giving it much thought, we stake our privacy on the exigencies of the market.

There are, for the moment, only two remedies, and we’d be wise to employ them in equal measure. The first is a healthy skepticism, motivating us both to question what’s being done with the information we volunteer to businesses by way of their social media networks and to opt out when we’re unsure of the cost.

The second is regulation. We need clearer laws defining ownership of personal data and restricting how third parties—including our own governments—can use it. The obstacles to that goal are numerous, including the resistance of a wealthy and regulation-adverse tech lobby and the difficulty of educating legislators on a rapidly shifting subject.

Those are obstacles we’ll have to overcome, but there is no viable alternative in remaining apathetic. In the absence of strong legal safeguards, we’re bound to find ourselves increasingly at the mercy not only of commercial technology providers, but also of government agencies less and less beholden to the people’s will.

Photo by Josef F. Stuefer/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed