When you use your phone, who’s listening in? In an era of warrantless wiretapping, it’s not surprising that you might be a little wary about phoning a friend, but it’s not just the feds you have to worry about. Police across the U.S. have also been working with mobile spying technology. Using a system called Stingray, they’re setting up fake phone towers and using them to listen in on your phone conversations. It’s one in a long line of recent police surveillance developments, which raises an important issue: Can regulation keep pace with new technologies, and assuming that’s possible, will it?

The exact number of U.S. cities using Stingray isn’t known, which is perhaps more terrifying than knowing that the technology exists at all; evidence suggests that Oakland, California, Tacoma, Washington, and Baltimore, Maryland are all using the equipment. Given the fact that the manufacturer earned $534 million last year, it’s safe to bet that more cities are using Stingray devices, and that their usage will spread.

Stingray equipment takes advantage of existing insecurities, the same ones that can be exploited by blackhat hackers and others. By routing calls through a fake tower, police departments can collect any and all data transmitted through the tower—including conversations, location data, and more. Consumers have no protection against the technology, as they can’t even detect it in use without special equipment, and police departments are notoriously close-lipped about its deployment.

When pinned down, police claim they only use the technology in combination with a warrant. After receiving a warrant, they track a specific cell phone with its unique serial number, allowing them to retrieve location data and listen in on phone calls—a potentially powerful tool for tracking people in a variety of settings, claim police. In theory, irrelevant data either wouldn’t be collected, or would be discarded.

But there’s a catch, as an op-ed in the Bellingham Herald makes very clear:

The TPD at first wouldn’t acknowledge that they even had one; Martin had to ferret out its existence from city documents. The department got the device from the feds in 2008, but its transfer and use was subject to an FBI non-disclosure agreement. Police Chief Don Ramsdell described it to city staff last year as bomb squad equipment. Some City Council members say they had no clear idea what it really was.

Furthermore, those same judges who are theoretically granting those warrants?

Judge Ron Culpepper, who presides over the Pierce County Superior Court, told The News Tribune’s Kate Martin that he’d never seen the Stingray mentioned in warrant applications—and that his fellow judges had never heard of it. That’s not real judicial oversight…For that matter, the county’s public defenders didn’t seem aware of it—a big opening for tainted evidence.

The total secrecy surrounding the systems illustrates a serious problem with U.S. law enforcement. While police departments are, in theory, responsible for serving and protecting the public—enforcing safety laws, investigating crimes, and performing other basic tasks—they’re now turning into spy agencies. Like their federal counterparts, they’re doing so with no accountability or transparency, with the use of technologies that allow for indiscriminate, wide sweeps of civilian data.

Essentially, Stingray systems verge dangerously close to illegal search and seizure. The Department of Justice has suggested in the past that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy on cellphones, and, therefore, that the technology doesn’t violate the law, but some judges aren’t convinced. The government claims it can’t disclose key data about the technology and its deployment because it might compromise security, but not all judges, especially those who have strong opinions on civil rights, are convinced by this argument.

If a technology is going to be used on civilians, surely they have a right to know what it is, how it works, and how it has the potential to be used against them. They should also have the right to know what kinds of legal protections they have, which gets to the crux of the problem with this kind of technology: Lawmakers are not able to keep pace with developments in surveillance technology, and citizens are the ones who pay the price.

The shady, mysterious Stingray systems may be advantageous to police departments and other agencies who enjoy the ability to use them without any transparency requirements or restrictions, but they’re not fair to civilians. Lawmakers, meanwhile, are as clueless about how these and other systems work as many civilians (and, apparently, some of the judges making rulings on their use). How can lawmakers be expected to pass effective legislation to control the manufacture, distribution, and use of such systems?

More to the point, perhaps, even if lawmakers did comprehend surveillance technology, would they defend civil rights by passing legislation to restrict its use? In a post September 11 climate, Congress hasn’t shown much aggression when it comes to protecting privacy rights and respecting civil rights overall, which bodes ill for creating limitations on spying technology. Even in the wake of the NSA spying scandal, Congress still cites the problem as one of isolated instances by rogue individuals, not a collective, institutional attitude in favor of spying technology.

Phone interceptor technology is evolving just as quickly as new networks, with interception equipment for networks up to 4G on the market, and it’s also keeping pace with phone security protocols, making it functionally impossible for consumers and providers to protect themselves—though, of course, providers seem happy to turn over records by request anyway.

Writing for Wired, Stephanie Pell cuts to the heart of the issue:

Chairman Wheeler’s framing of the task force as addressing the ‘illicit use’ of IMSI catchers hopefully represents a positive initial step towards protecting our cellular communications. But to the extent that the task force’s efforts only focus on ‘clamp[ing] down on the unauthorized use’ of the devices, the Commission’s efforts will do little if anything to protect cellular communications from IMSI catchers, much less from broader exploitation of the network vulnerabilities that enable their use.

When the precise definition of “illicit use” isn’t clear, it opens up rather terrifying possibilities. Given precedent, it’s unlikely to see police forces being targeted for illicit use of the technology, such as the unauthorized collection of private data. By default, it is assumed that any use by police is authorized. Any laws regarding interception equipment are likely to be aimed at individuals, not law enforcement agencies, as Congress may be reluctant to or uninterested in reining in local police departments.

Yet, such departments shouldn’t be allowed to have technology with such a broad scope of applications. Aside from the fact that it’s a clear violation of civil rights, most police departments don’t have the training required to handle classified information of this nature, to purge material unrelated to investigations, and to secure evidence to ensure that personally identifying information isn’t released. This opens up too many possibilities for abuse, yet Congress hasn’t moved on the issue, despite the fact that the existence of the technology is a well-known and well-understood, phenomenon.

Should we have faith in our legislators to curb the use of interception technology? Probably not—and that brings us around to the fact that many of us not only fear our government, but actively don’t believe that it can act in our best interest. The culture of security theater created in the United States in the last 13 years may be irreversible, even with privacy advocates pushing back on issues like this one.

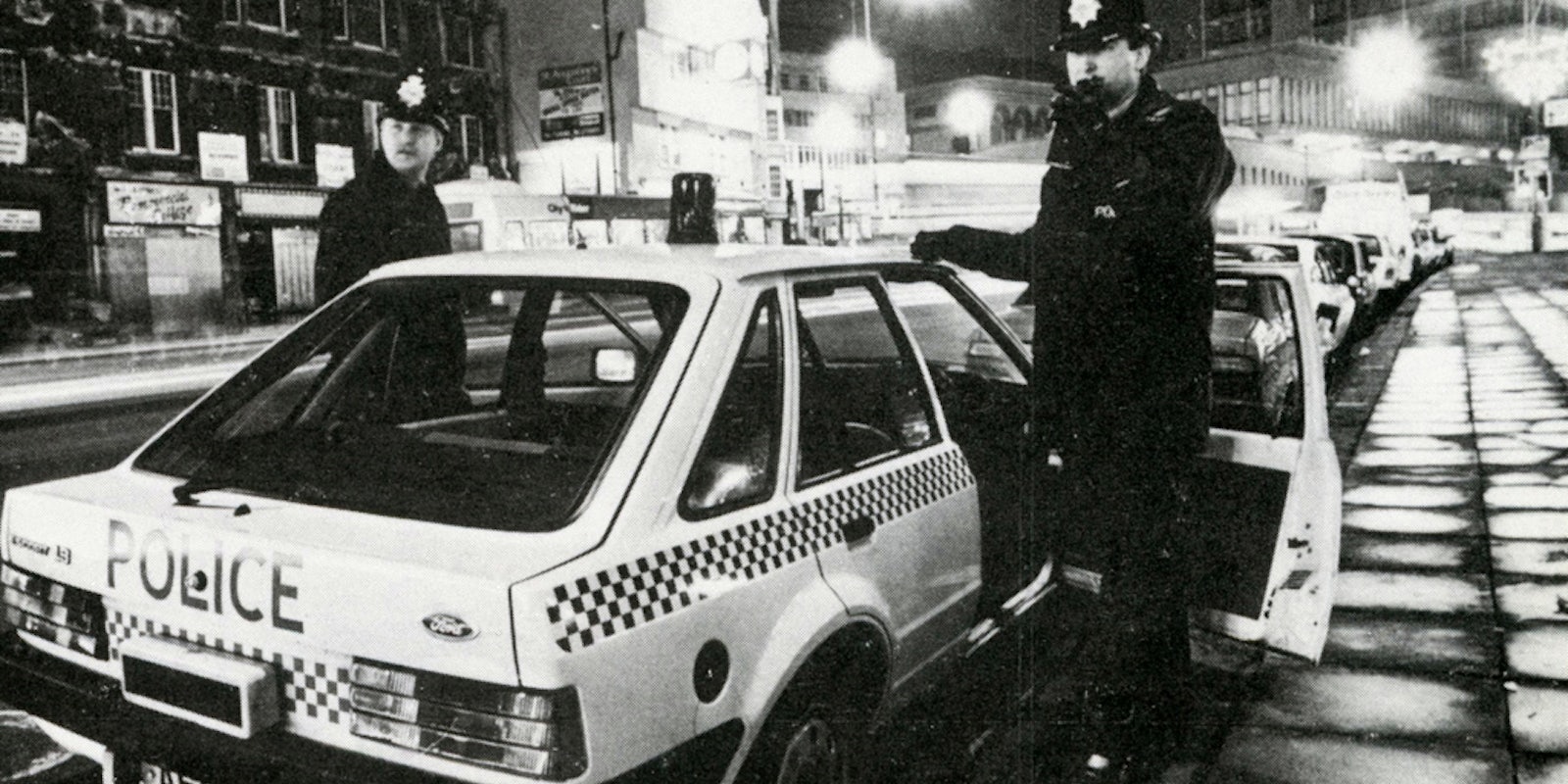

Photo via brizzle born and bred/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)