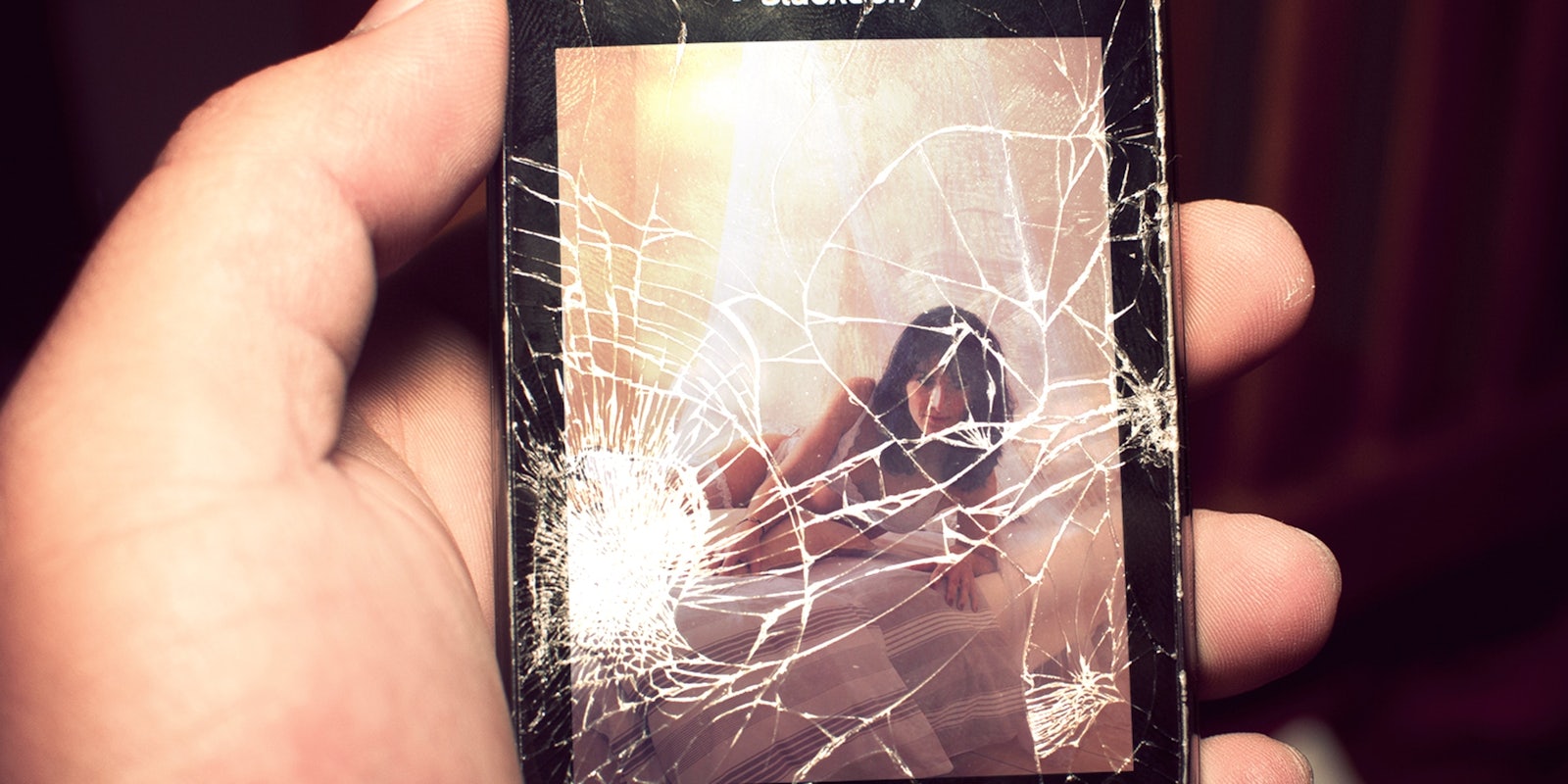

In a paean to photo-sharing service Instagram posted at The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer paints an image of a serene, peaceful social network. It’s a far cry from the frenetic, troll-laden, chaotic Web services most of us deal with every day—the fights with family members on Facebook, the relentless harassment on Twitter, the trolling on Reddit, or the internecine wars of Tumblr. But beneath the surface of the cool, refreshing waters of Instagram lies a shark, and it’s ready to bite.

Meyer’s experience of Instagram is as a friendly, supportive place that’s easy to dip in and out of, with a simplistic, clear, uncluttered format. “It is made of pictures, not text, which makes it less political than Twitter or Facebook, and therefore cheerier,” Robinson writes.

But this dreamy view doesn’t address the dark side of Instagram: the harassment and abuse of users who become targets because of their high public profiles or non-normative bodies. The average white guy posting pictures of his cats doesn’t experience Instagram in the same way a plus-size woman of color does, and it’s time to stop avoiding these issues.

Meyer’s analysis misses the political power of images and the fact that for many users, the personal is political. For plus-size model Tess Holliday, for example, just posting photographs of her body is a defiant political act, and notably, she’s repeatedly slammed for her looks with trolling comments about her body below almost every single post.

https://www.instagram.com/p/11OfIKgPg1/

#YesMyOrgansAreFab, she notes, responding to frequent concern-trolling on her posts about her health; other commenters are more aggressive, referring to her as a “freak” and making snide comments about her looks. Her body is a dramatic personal statement, but also a political commentary on social expectations surrounding women’s appearance.

This kind of public harassment of high-profile women isn’t the end of the line, as illustrated by a recent case involving a middle-school student. She was sent escalatingly graphic messages, and it took nearly a week for Instagram to respond to her harassment—even after repeated requests for help from her parents and the school district.

In 2014, Robin Williams’ daughter, Zelda, briefly left the service following after users sent her “photoshopped images of her father’s dead body and other disturbing messages—some blaming her for father’s death,” as CNN reported. These incidents illustrate that Instagram can be used for cyberbullying as readily as any other online service.

Instagram abuse can get ugly, as in the case of deadanimalsikilled, an admittedly tacky satirical account featuring—you guessed it—photos of dead animals the administrator claimed to have killed. (One photo included a bald eagle, so probably not.)

The average white guy posting pictures of his cats doesn’t experience Instagram in the same way a plus-size woman of color does, and it’s time to stop avoiding these issues.

The account’s following remained relatively small until 2014, when it hit a tipping point after German teenagers found the account and launched a crusade against its admin. One Instagram user told him: “In Germany we had a place for you. That place was Auschwitz. Now step in the train.”

However, those were far from the only death threats he received. “If I knew where you lived, I would kill you and take a picture of it and put it on Instagram. How would you feel, you Ass Birth,” another wrote.

While the admin told Vice magazine that these threats were very common, Instagram itself didn’t take action against him. “So far [the administrators] have been totally amicable,” he said. “They have a sense of humor, I guess.” The account has since been deactivated.

The satirical account might not be posting images of flowers and tea sets, but the vitriolic response speaks to an undercurrent of potentially violent abuse on the platform, waiting to surface upon provocation.

And that harassment can have deleterious effects on users’ offline lives: After William Moreno was accused of rape by a targeted harassment campaign against him, a lawsuit filed against his trolls alleges that “mass-bombing threats were posted under his name, his parents’ house was vandalized, he received death threats, his car was broken into, and his mother’s job was put in jeopardy.”

Following two years of constant abuse, Moreno attempted suicide in 2014.

It would be nice to find “the nice Internet,” where nothing bad happened and everyone enjoyed being part of a supportive community. Knitting site Ravelry may actually come closest to this idyll, but Instagram isn’t the oasis we’re looking for, despite the friendly subcommunities that exist on the site, like the members of #caturday, #transguys, and #amreading, who rejoice in subjects of mutual interests and frequently leave supportive, encouraging comments on each others’ photos.

https://www.instagram.com/p/5TE6giBCeh/

There’s a reason the site recently updated its guidelines to crack down on harassment, reflecting the fact that as Instagram grows, so too does a culture of unfriendliness seeping into its once-bucolic environment. It’s possible to avoid casual cruelty and outright viciousness with a carefully curated following list, but pretending it isn’t out there is a disservice to Instagram users struggling with harassment and abuse.

If we fall into the trap of wearing rose-colored glasses when we look at Instagram, we make it much harder to acknowledge and fight the burgeoning culture of harassment on the platform. Across the Internet, abuse is becoming a growing problem, and the little photo site that could is no exception. Dragging #InstaHarassment into the unfiltered light of day is the only way to start solving the problem.

S.E. Smith is a writer, editor, and agitator with regular appearances in the Guardian, AlterNet, and Salon, along with several anthologies. Smith also serves as the Social Justice Editor for xoJane and will be co-chairing Wiscon 40—the preeminent feminist science-fiction conference—in 2016.

Photo via Rafael Castillo/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) and Patrick Subotkiewiez/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)| Remix by Max Fleishman