Some of my fondest childhood memories were set in libraries. I still recall wandering through stacks of books, my eyes glancing from title to title in the hope that they would land on some previously undiscovered treasure. Sometimes I would take a step into the past by setting up a roll of microfilm and letting it whir through the scanner until it landed on an intriguing story from a bygone era.

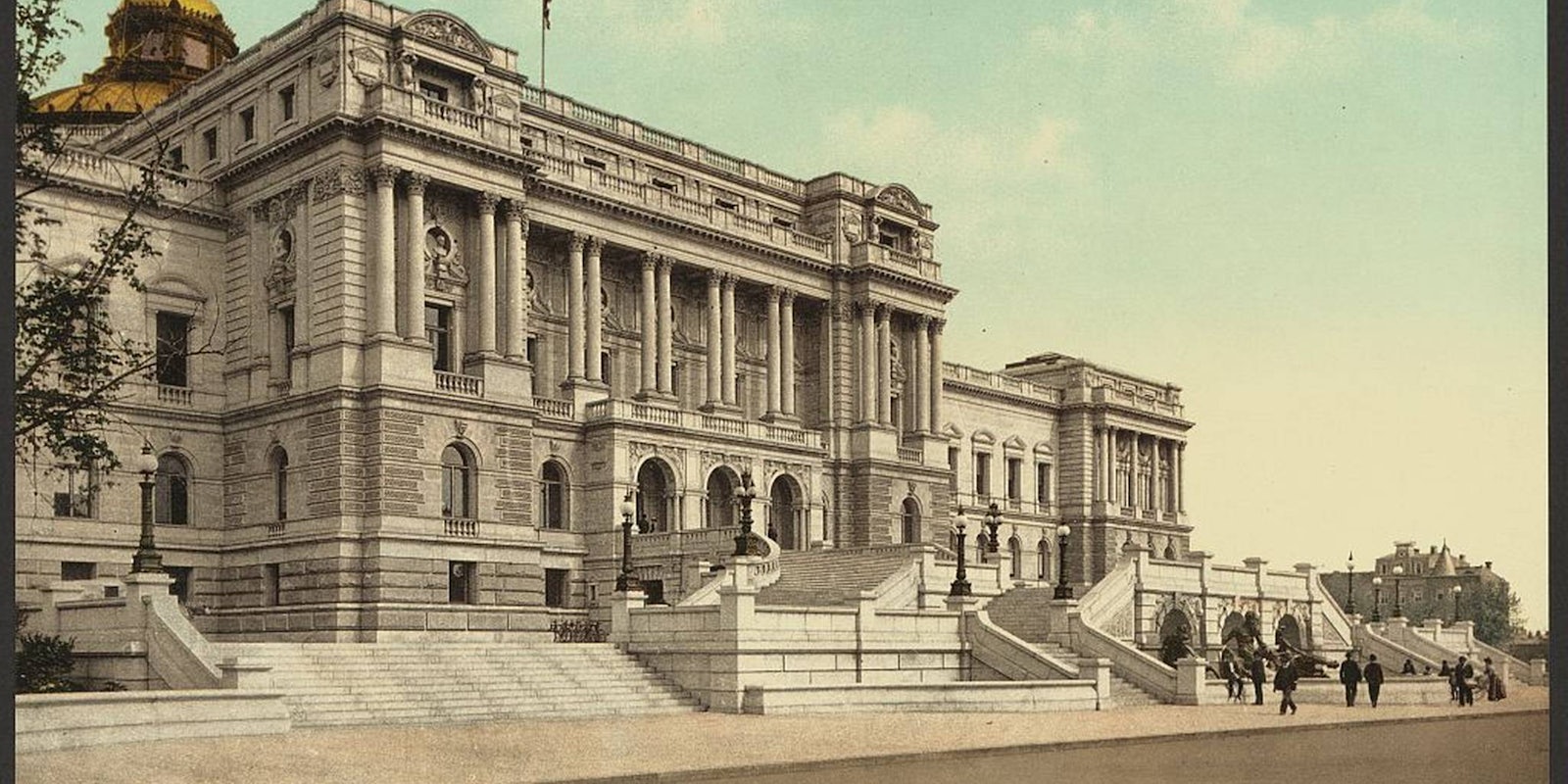

The sights, the sounds, even the smells of these libraries linger in my brain long after I last set foot in them. As the Library of Congress celebrates its 216th anniversary today, it’s worth taking a moment to ask: What sources will be available to future young scholars?

The Library of Congress is one of the oldest cultural institutions in Washington, D.C. Founded as a legislative library in 1800, it gradually expanded into that of an all-purpose center for scholarly research; as a result, it is currently the largest library in the world. Its collection includes “more than 38 million books and printed materials, 3.6 million recordings, 14 million photographs, 5.5 million maps, 7.1 million pieces of sheet music, and 70 million manuscripts.” On top of this, the library “receives some 15,000 items each working day and adds approximately 12,000 items to the collections daily.”

What sources will be available to future young scholars?

Needless to say, this is quite a step forward from 1815, when the library became an international sensation after purchasing 6,487 books from Thomas Jefferson’s estate. Now in a world where we live online, through social media posts and websites and email, it’s hard to imagine how we will preserve our digital future. The days have long past in which a library’s responsibilities were limited to safeguarding and cataloguing books.

This is why Michael Agresta writes in Slate that “a library without books was unthinkable. Now it seems almost inevitable.”

After discussing how the advent of the Internet has caused a decline in library attendance—and, in many cases, sharp cuts in funding—Agresta points out that “librarians have begun to identify a rationale for institutional survival in … ancillary public benefits.” To cultivate this image, many libraries establish “maker spaces” in which bookshelves have been replaced by collections of old and new technologies, where people can study in ways that aren’t necessarily possible with only an Internet connection.

This trend is also evident in Britain, where the Independent Library Report discovered that libraries are actually making a comeback by reinventing themselves as community hubs that focus on “the need to create digital literacy—and in an ideal world, digital fluency.”

Similarly, a 2013 Pew Poll found that 90 percent of respondents believe their communities would be impacted if public libraries closed. By recasting libraries as loci of digital scholarship—places where anyone can come, regardless of their economic background, and have access to both the Internet and a wide range of digital resources—modern libraries have found new ways of staying relevant in the 21st century world.

There are concerns about the mass digitization of libraries.

In that same year, the Boston Public Library launched the Digital Public Library of America, which endeavors to make the holdings of America’s research libraries, archives, and museums available to all Americans free of charge. As Robert Darnton of the New York Review of Books explains, “[T]he DPLA will be a distributed system of electronic content that will make the holdings of public and research libraries, archives, museums, and historical societies available, effortlessly and free of charge, to readers located at every connecting point of the Web.” While it won’t serve as a substitute for the communal atmosphere provided by institutional libraries themselves, it will allow them to maintain an indispensable role by channeling their resources to broader audiences throughout the nation—in effect, taking libraries home to each and every American.

There are concerns about the mass digitization of libraries, however.

“What worries us all,” explains Nancy Cline, Larsen librarian of Harvard College, in an interview with Harvard Magazine, “is that we really haven’t tested the longevity for a lot of these digital resources.” Whereas paper and ink are physically tangible and thus capable of being preserved throughout the generations, digital technology has only existed for a few decades. There is no reliable way of knowing whether these materials will remain intact, become degraded, or in some other way get compromised. In a worst-case, nightmarish scenario, it is entirely possible that millions of pages of material could be wiped away overnight.

This brings us back to the future of the Library of Congress. On the one hand, it is important that the Library of Congress embrace the same “maker space” mentality that is helping smaller libraries remain relevant. Because the Internet and projects like DPLA have given ordinary citizens access to the kind of information that used to only be available at libraries, it is no longer sufficient for the Library of Congress to merely view itself as a repository for data. It needs to also recognize its potential as a place where individuals can congregate for scholarly purposes, a need that cannot be met from an iPhone or one’s home computer.

At the same time, we need to be careful about letting technological progress blind us to the verities of tried-and-true methods of preserving information. There is a good reason why paper-and-ink have endured for so long as the main method of record-keeping, whether for novels and other fictional literature to scholarly works. We know that it is effective, and consequently, the Library of Congress should never allow the passion for digitization to cause it to dispense with books in the process.

This is one of those rare situations in which we not only can have it both ways, but should absolutely insist on doing so. I say this not only as a Ph.D. student and writer, but as the adult counterpart to that curious teenager who made an informal home in his local libraries.

Editor’s note: This story has been edited for clarity.

Matthew Rozsa is a Ph.D. student in history at Lehigh University and a political columnist. His editorials have been published on Salon, the Good Men Project, Mic, and MSNBC. Follow him on Twitter @MatthewRozsa.