OK, America. We really, really need to talk about our collective paranoia over false rape allegations.

One in six women will be the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime. One in thirty-three men will be the victim of an attempted or completed rape in his lifetime. Each year, thousands of Americans report claims of sexual assault or rape, and according to the Federal Bureau of Investigations, only between 2 and 8 percent of these accusations turn out to be “unfounded” or false. So why is every story of sexual violence that unfolds in the national media met with an instant parade of scrutiny, doubt, and, more and more often, aggression?

A lot of minds will immediately jump to “Jackie,” the young woman at the center of Sabrina Erdely’s Rolling Stone article about the University of Virginia. Now known as the world champ of bad journalism, Erdely graphically detailed the alleged gang rape of a University of Virginia student at the hands of seven members of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. The story unraveled almost immediately when people started asking questions. The media immediately drew comparisons to the high profile Duke lacrosse scandal and the Tawana Brawley hoax—three cases of alleged gang rape where evidence to support the victims’ claims could never be substantiated.

And then we have Emma Sulkowicz, who made headlines after going public with allegations that she was raped by fellow Columbia student and former friend Paul Nungesser. Columbia cleared Nungesser of responsibility following a disciplinary hearing brought by Sulkowicz. Her case was eventually dismissed by the New York district attorney’s office, citing a lack of evidence.

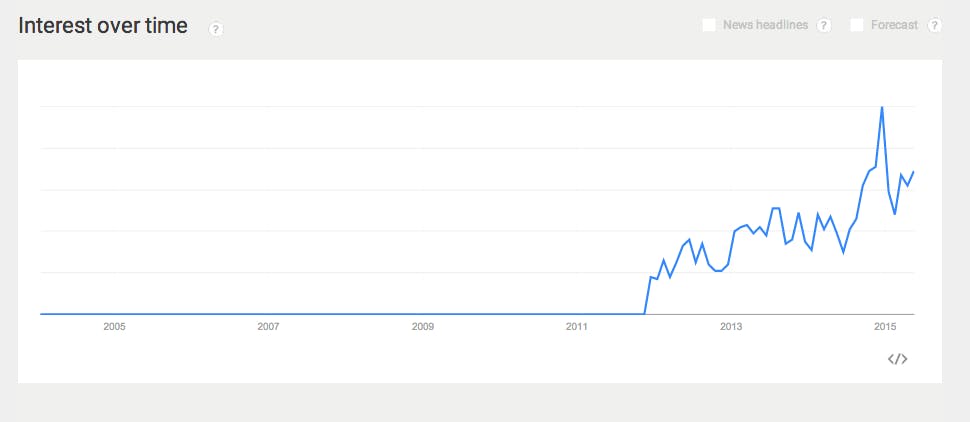

Responses to Erdely’s article usually fall squarely within the category of disgust, but reactions to Sulkowicz’s vocal disavowal of the way Columbia handled her case have ranged from skeptical to downright apoplectic. This isn’t particularly unusual; public reactions to cries of “false rape accusation” are typically vitriolic. While these stories swirled in the vacuum that is the national 24-hour news cycle, Google Trends indicated a huge spike in searches for the term “false rape accusations.”

My own search didn’t reveal a litany of false rape cases though—instead, what showed up was page after page of articles from Men’s Rights websites discussing what to do when a woman inevitably (according to them, anyway) accuses you of rape.

Of the 293,066 victims of sexual assault and rape every year, our focus is being pulled to the stories of a handful of young women. And the public analysis of the words and actions of these women has been seriously dubious. “Jackie” may have fabricated her story at the behest of Sabrina Erdely (who admits that she was searching for the “right” campus to focus on) and the complexities of Crystal Mangum’s accusations in the Duke lacrosse case may never be fully unpacked (Mangum maintains in her memoir, The Last Dance for Grace, that she was raped), but we can’t allow these cases to permanently color the way we respond to claims of sexual assault.

Just ask Emma Sulkowicz. After her alleged rapist was found “not responsible” by Columbia University and her case was dropped by the DA, Sulkowicz and 27 other students filed a federal complaint against the school for their handling of sexual assault cases. That makes Columbia one of 95 institutions of higher learning under investigation by the Office for Civil Rights for how they handle sexual assault complaints.

The idea that Emma Sulkowicz and the three other people who have accused her alleged rapist of sexual assault are some kind of anomaly is ridiculous. Especially when we remember that much of the outcry surrounding her case comes from the fact that the encounter between Sulkowicz and Nungesser began as consensual and came after two other instances of consensual sexual activity.

If you’ve never been a victim of sexual assault, maybe it’s difficult to understand how complex and emotional the experience really is. It’s especially confusing if the person that assaults you is someone you know and trusted. Much of the outcry in response to Sulkowicz’s claim that she was raped comes from the fact that people simply don’t seem to understand that giving consent once does not guarantee continued consent. When her Facebook chat logs were released, people seemed dumbfounded that Sulkowicz would continue to message her alleged rapist after the incident occurred, but her response to Jezebel reveals an inner process that other victims may identify with.

Two days after she was assaulted, Nungesser invited her to a party in his room. Sulkowicz responded “lol yusss. also i feel like we need to have some real time where we can talk about life and thingz.” In her annotations to Jezebel, she writes, “I haven’t faced him since he assaulted me, and I want to talk with him about what happened. I try to say this in a friendly tone, so that he doesn’t get scared. I don’t want him to avoid the conversation. I’m being irrational, thinking that talking with him would help me.”

The fact that Sulkowicz has had to go to such lengths to to meet public demand for an “explanation” is alarming. But just look at the backlash she has faced. Earlier this week, someone papered the streets of Manhattan with posters bearing Sulkowicz’s image, standing beside the dorm mattress she carried for two years during her performance piece “Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight),” a response to her alleged rape. The words “PRETTY LITTLE LIAR” hover over and on top of her body, and “Columbia #RapeHoax” sit at her feet.

https://twitter.com/Ash_Effect/status/601879975206072320

https://twitter.com/RemipunX/status/601740832903921664

Fascist little girl is mad that people refuse to pretend that lies are truth. #RapeHoax @AskAngy @jtLOL https://t.co/qZUzihA7G4

— Kurt Schlichter (@KurtSchlichter) May 21, 2015

A Twitter user under the handle @fakerape has taken responsibility for the poster campaign (which also includes images of Lena Dunham with the words “BIG FAT LIAR”), telling amNewYork’s Alison Fox via Twitter, “We want to educate people about fake rape claims & how damaging they are. From UVA to Columbia to UMiami, due process matters.”

If only 2-8 percent of rape claims end up recorded as “unfounded” or false (and “unfounded” can simply mean that a case was dropped due to a lack of evidence, not necessarily that an assault did not occur), then why do we need to “educate” people about them? The fact that there are so few of them (and that sexual assault has actually decreased by nearly 50 percent since 1993) should indicate that it’s basically a non-issue. Is @fakerape’s request truly rooted in concern for the public good or is it nothing more than good old-fashioned misogyny?

Sulkowicz wasn’t @fakerape’s only target: Posters of Lena Dunham‘s face with the caption “BIG FAT LIAR” also appeared. But crying “fake rape” at Dunham doesn’t even make sense: She never publicly accused her attacker, she only identified him by a pseudonym in her memoir Not That Kind of Girl. When a man that matched her description was called into question as her alleged rapist, Dunham responded in a piece for BuzzFeed: “Speaking out was never about exposing the man who assaulted me. Rather it was about exposing my shame, letting it dry out in the sun.”

By now, I think we can identify a pattern. Women (and, less often, men) are being attacked for coming forward about sexual violence due to a climate of systemic paranoia over false rape claims. That paranoia has always been there, rooted in a distrust of women’s abilities to provide truthful, rational information about their bodies and their experiences.

If only 2-8 percent of rape claims end up recorded as “unfounded” or false, then why do we need to “educate” people about them?

But the rise of online spaces catering to the growing Men’s Rights movement certainly hasn’t helped. From communities like the National Coalition for Men and A Voice for Men to the popular Men’s Rights subreddit /r/mensrights (which has over 111,000 subscribers), men—and some women—are gathering online to promote the idea that false rape accusations are more prevalent than the FBI and other organizations report. They also seem to believe that claims of sexual assault by women are some sort of epidemic.

Under the guise of “raising awareness,” these organizations and communities have created an even bigger obstacle for victims of sexual violence to overcome. Now, there’s one more thing to be afraid of when people come forward about their assault. There are issues of journalistic integrity here as well (Rolling Stone‘s nonexistent fact-checking and the release of Paul Nungesser’s name to the media, for example), but the rage that came to a head with the @fakerape campaign doesn’t really seem to be about that. There’s a festering pit of anger and suspicion underneath all of this, and we really, really need to deal with it.

Kayla Goggin has done most of her growing up in Savannah, Ga. She works in the third oldest synagogue in America but is not Jewish despite her growing yiddish vocabulary and knowledge of bagels. Kayla loves horror movies, looking at (but not talking about) art, and scouring America for the perfect old fashioned.

Screengrab via freespeechtv/YouTube