When a celebrity dies, everyone’s a eulogist.

Increasingly, the deaths of public figures are marked by “Twitter wakes,” a form of collective grief that transforms the everyday “cocktail party” of Twitter into a more somber occasion, at least for a day. A Twitter wake is equal parts group therapy and grist for the content mills, spawning memorial supercuts and wandering longreads of personal recollection.

The death last week of David Carr, a giant of media qua media at the New York Times, inspired one of the more well-attended Twitter wakes in recent memory. But whether due to the times we live in or the professional makeup of his mourners, Carr’s Twitter wake displayed a greater-than-average instance of one of the Internet’s most unlikable creations: the griefbrag.

A griefbrag is an expression of bereavement that says more about the speaker than the deceased. Like its well-documented predecessor, the humblebrag, the griefbrag is self-promotion dressed as self-effacement. By way of explanation, an example from director Darren Aronofsky, reacting to Roger Ebert’s death in 2013:

we lost a thoughtful writer, i remember my first review from him, pi (i got his and siskel’s thumbs) it was a career highlight. #rogerebert

— darren aronofsky (@DarrenAronofsky) April 4, 2013

This is a textbook griefbrag. It begins innocuously, acknowledging a collective loss—“we lost a thoughtful writer”—and closes with an offhand brag—“it was a career highlight.” In between is a reference to a favorable review of Aronofsky’s own work. Unlike a humblebrag, a griefbrag is typically well-intentioned and doesn’t always recognize itself. Expanded beyond 140 characters, Darren Aronofsky’s recollection might amount to a touching anecdote. But on social media, home of the humblebrag, it just looks crass—even when the tweeter is also a celebrity.

The death of Robin Williams late last summer flooded Twitter with movie quotes and personal memories of Mrs. Doubtfire and Dead Poets Society. But at least a few of even the most heartfelt goodbyes lapsed into the blindly self-referential mood of social media.

https://twitter.com/mindykaling/status/498993956781162496

https://twitter.com/WhitneyCummings/status/499065540250333185

None of these is a brag, per se, but none of them is simply a goodbye. Williams is mourned not (or not only) for the joy be brought the world, but for the specific relevance to each of these tweeters. Can they be blamed? Isn’t that, after all, the way each of us relates to the world at large? To wit, Jane Fonda’s rather robotic reaction to the death of Elizabeth Taylor, in 2011:

Again, not a brag—not even really much of a statement—but a goodbye that leads with “I” instead of “you.”

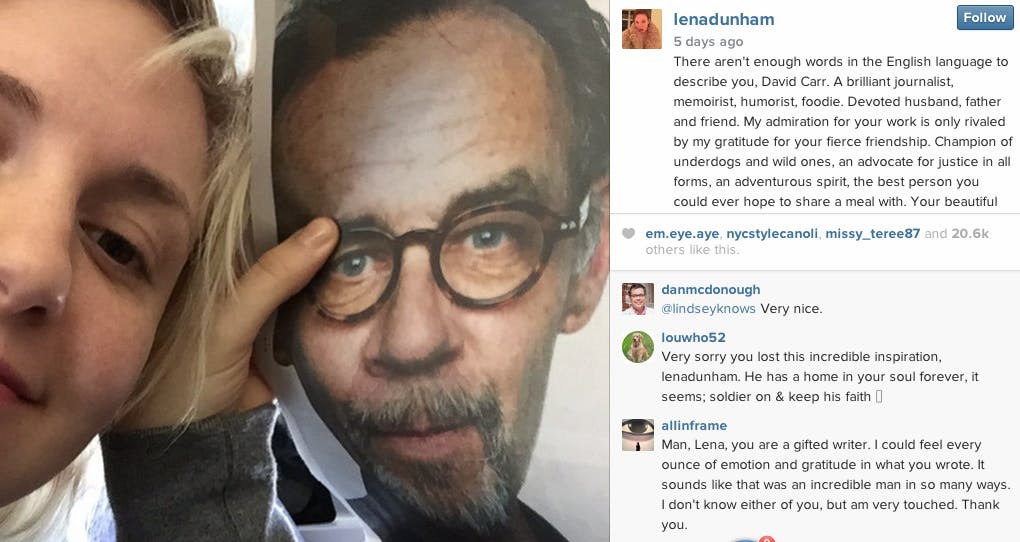

A more nuanced example is this Instagram post from Lena Dunham. The post is deeply sincere, but it displays the ultimate strangeness of posting intimate remembrances on social media. It’s no stranger than praying, perhaps, or leaving flowers in a cemetery—physical acts with spiritual aims—but the “likeable” nature of this style of grief perverts both the gesture and the sentiment behind it. Dunham’s photo literally places her beside the late Carr, his paper likeness stern and flat in the bizarre context.

Most of the griefbragging that followed news of Carr’s death came in the form of glowing personal remembrances, which cropped up everywhere from the New Yorker to Gawker. “Over the last decade David Carr poured buckets of advice on me,” wrote Times columnist Nick Bilton, who also griefbragged a candid photo of Carr in his backyard. Bilton’s was among several tributes to be posted last week, including the same story from two different people.

These read like a chorus of eulogies—the return on investment for a career spent inspiring writers—painting portrait after portrait of someone everyone seems to agree was a lovely and talented person. If, as John Cook claims in his own Gawker tribute, “everyone has a David Carr story,” it’s hardly surprising there has been such a wealth of remembrance. But what Cook calls David Carr stories turn out, in most cases, to be people-who-have-David-Carr-stories stories, the authors remembering themselves remembering David Carr—in other words, griefbragging.

Many of these pieces are stirring, poignant, and honest about the experience of loss and what stands out in memory. Many are more or less personal essays written on a prompt. The very fact of all these stories and storytellers have come forth in the wake of one man’s life is a testament to how he spent it. But in the realm of social media, and particularly among the content creators, the writer often stands too comfortably in the role of subject, and even potentially great Internet eulogies are reduced to hot takes.

In the long history of human death, grieving online is new, and the funeral rites of the Internet are still being written. Much of the social behavior we’ve constructed around death IRL doesn’t, hasn’t, or can’t translate to social media, and Emily Post has not yet codified the etiquette of Twitter wakes.

We live our online lives through a filter of self-reference, constructing a personal brand that doesn’t exist (or isn’t as literal) in actual life. Sharing memories of the deceased among friends is a natural and cathartic act of grieving; sharing memories on Medium looks like grim famewhoring. What reads as a griefbrag to one person may be simply a touching personal memory to another, and maybe some of us are just too cynical. Maybe. The griefbrag is a gray area, with highly subjective boundaries.

Grief itself is one of the least self-important emotions a person can have, if you’re doing it right, and yet, on the Internet, every act is an act of self-promotion, however minor or unintentioned. As honestly saddened as we may be at a famous person’s death, celebrity mortality weighs on most of us probably not much longer than the moment it takes to compose a #sinceretweet, or to tap out “#RIP.”

As a news item, the average celebrity death lasts only slightly longer than the average ill-conceived thinkpiece. (Remember the Guy Who Hates Brunch?) Even as I write this, David Carr’s Twitter wake is receding into the distant Internet past of four days ago. Before long, his will be eclipsed by another. The throughline of Twitter wakes is their attendants, the Twittersphere looking on with earnest #feels and the optical illusion of a trending topic that suggests any of us might be as relevant to someone’s death as it is to us.

Photo via wiobyrne/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)