By now you’ve probably heard of Yik Yak, the anonymous social media app that gained popularity on college campuses across the United States.

It’s raised somewhere in the range of $73 million from investors, the largest chunk coming in November 2014 in the form of a $62 million round of financing from venture capital firm Sequoia Capital. The round valued Yik Yak at between $300 to $400 million.

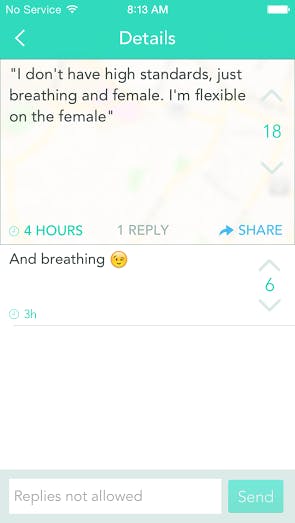

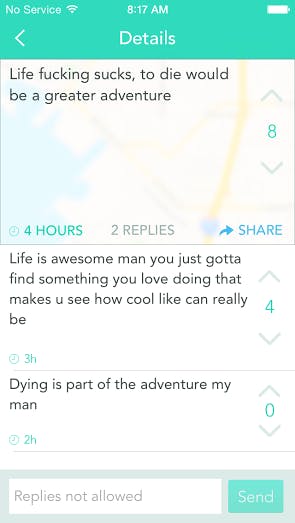

Despite its market success, controversy plagues Yik Yak. The combination of youthful stupidity, lack of empathy, and anonymity has turned the app into a battlefield for social decency.

Everywhere Yik Yak appears, so do contingents of kids, parents, and administrators who don’t want the app anywhere near their schools. And the controversy just continues.

Early on in the app’s existence, Yik Yak founders Tyler Droll and Brooks Buffington made the decision to place a self-imposed ban at middle schools and high schools. Accomplished via geo-fencing, the initiative to keep kids off the app is unprecedented—it’s not too often an app tries to prevent one of its primary demographics from using it. (See: After School; one school recently had to shut down as a result of threatening messages.)

But the effort came after schools were already trying to rid Yik Yak from its classrooms. Chicago-area high schools began issuing warnings about the app as early as February 2014, asking parents to delete the app from their children’s’ phones and placing what amounted to symbolic bans on the app from the school’s wireless network.

A student at Whitney Young High School in Chicago told the local ABC affiliate other users on the app “ripped on someone about getting raped.”

The situation spread so quickly throughout the city, Yik Yak blocked itself in the entirety of Chicago until it was able to eventually fence off specific schools, which in turn resulted in the nationwide middle school and high school exile (thanks in part to encouragement from the National Association of People Against Bullying). Yik Yak has also listed its app with an age rating for 17+, allowing parents to block it using parental

controls.

Still, the app continues to persist at some high schools. The database used for geo-fencing, provided by Maponics, covers 85 percent of American schools. Yik Yak has offered to handle any case wherein the app is still accessible on school grounds, but there’s little it can do to keep students from using the app elsewhere. Students can use the app at home and wherever teens hang out. (Are soda shops still a thing?)

Yik Yak offered to implement its geo-fencing system at Westlake High and other schools where the app was still active, like Lincoln High School in Rhode Island. The school and its surrounding district took to working with Yik Yak to make sure the app was rendered inaccessible. “The superintendent is really concerned about bullying all across the district and won’t tolerate it,” Lincoln High School Principal Kevin McNamara told the local NBC affiliate.

Below is a list of high schools that have banned Yik Yak:

-

Westlake High School in Texas are blocking Yik Yak and have threatened suspension or expulsion if a student posting hurtful content is identified.

-

Cincinnati’s CBS station reports that a school in Ohio did the same because. “The posts were so demeaning, so vulgar, so racially and sexually harassing to other students that we felt like we had no other choice but to act on it quickly.”

-

In Tatum, N.M., Yik Yak inspired a cell phone ban.

-

Columbus public schools had staff monitor Yik Yak before banning access to the app while on school grounds.

-

Arrowhead, Burlington, and East Troy school districts in Wis. enacted bans on Yik Yak, enforced through geofencing.

-

Profanity and hate speech were cited as reasons to ban the app at a variety of tri-state area schools in New Jersey.

The most common charge against Yik Yak is bullying—harassment and vulgar attacks posted without fear of repercussion thanks to the shield of anonymity.

But there are problems beyond harassment. Threats to the safety of students and faculty that have surfaced on Yik Yak have led to swift action against the app and the involvement of law enforcement.

The earliest account of criminal response to Yik Yak dates to February 2014. Threats of a shooting at McGill-Toolen High School in Mobile, Ala. were posted on the app. Parents rushed to the school, and kept students home the next day. According to reports from the local Fox and CBS stations, additional threats popped up at nearby schools including St. Ignatius Catholic School, Saint Paul’s, Murphy High School, and UMS-Wright Preparatory School, an indication of copycatting if there ever was one.

Two students were arrested for the threats. Mobile County District Attorney Ashley Rich said the arrests would not be possible had Yik Yak not assisted in the investigation.

Just a few weeks later Marblehead High School in Mass. encountered similar posts inciting the possibility of violent acts, including bomb threats that forced the school to evacuate on two separate occasions. Police in Marblehead contacted police involved in the Mobile, Ala. case and likewise worked with Yik Yak to apprehend one of the posters.

And this was just the beginning.

-

At Liberty High School in Bakersfield, Calif., a 16-year-old attempted to goad other users into upvoting his post by promising to “Sandy Hook” his school if he received 1,000 upvotes. The student was promptly arrested and held at a juvenile center on suspicion of a public nuisance.

-

A teenage student at Mount Sinai High School in Long Island, N.Y. threatened a bombing and shooting at his school in September. He was arrested and booked with making terrorist threats against the school; he was charged as an adult.

-

A day later in Westchester County, N.Y., a student posted that Yorktown High School “will explode.” He too was charged with a terrorist threat but was charged as a minor.

-

Ludlow High School in Mass. increased its police presence after a threatening post was made near the school. Some parents pulled their kids from classes upon receiving word of the threat. The Ludlow Police arrested 18-year-old Matthew E. Kurtz, a former student, for the post.

-

17-year-old Manuel Castanon was arrested by Hendry County police in Fla. after posting a threat to shoot up the school’s cafeteria. According to his friends, he posted the threat after being the subject of hours of ridicule on Yik Yak.

-

Eric Wood, a 19-year-old in Sellersville, Penn. left a post near Pennridge High School that read, “Hey guys, I’m not in school anymore so ha. I’m bringing a gun though tomorrow so watch out …or how about a bomb?” He was arrested and charged with terroristic threats and harassment.

-

Richard Christopher Patton of South Brunswick High School in N.C. was arrested and held on $10,000 bond—which was posted and he was released—after posting “Bomb at South today. Watch out!”

-

A post reading “I’m going to shoot up the school” prompted schools in the East Troy school district in Delavan, Wis. to go into lockdown. The poster was eventually apprehended.

-

Despite attempts to block the app earlier in the year, police in New Richmond, Ohio arrested a student after he threatened to “shoot up” the school.

-

Washington High School in Daviess County, Wash. was evacuated for two hours after school officials became aware of a bomb threat posted to Yik Yak. 18-year-old Dakota Tipton was arrested and faced charges of intimidation, a level six felony.

-

Two students at different schools in Franklin County, Ala. were arrested on separate charges of bomb threats on the same day: A 16-year-old at Russellville High School—charged with making a terrorist threat and rendering a false alarm—and a 17-year-old at Tharptown High School—also charged with a terrorist threat.

-

Three students (one of whom was 13) were arrested by the Pleasant Hill police in Iowa following coordinated threats posted on Yik Yak against Southeast Polk schools. Charges ranged from intimidation with a dangerous weapon, first-degree harassment, threats with an explosive device, and terrorist threats.

-

In what are believed to be unrelated threats, a 16-year-old girl was arrested for a threat against Canyon Crest Academy and a 17-year-old boy was arrested for a threat against Torrey Pines High School in San Diego.

-

Washington Court House City schools were instructed by authorities to ban book bags, requiring students to carry their books and school materials while the campuses were swept for bombs following a threat to blow up the school appeared on Yik Yak.

-

Two high schools in Southern California were placed on lockdown after a bomb threat was posted on Yik Yak. One suspect was taken into custody.

-

A sophomore at Mason High School in Mason, Ohio was arrested after posting a bomb threat a week after the school district banned the app from its network.

“Columbine was nothing, I have access to a bunch of guns and am going to shoot up Drake.”

Bomb threats and threats of shootings appear on Yik Yak even among its older audience—so regularly, in fact, the first question on Yik Yak’s frequently asked questions page is “Can I post a threat without repercussions?” The response to the question is “No! Don’t be dumb. DON’T POST A THREAT. We take threats to safety very seriously and cooperate with local authorities if there’s a post that poses a threat to people.”

Yik Yak has made good on that promise. It worked with authorities after a Brooklyn student attending the State University of New York at Canton posted threats on Yik Yak. Alexis Vazquez was arrested after Homeland Security agents became involved in the case. This wasn’t the only case, however.

In Towson, Md., a Towson University student posted a treat to carry out “Virginia Tech part 2.” 18-year-old Matthew David Cole was charged with making threats of mass violence and disturbing the operation of the school.

After posting “Columbine was nothing, I have access to a bunch of guns and am going to shoot up Drake,” 18-year-old Drake University Michael Zachary Crisp was arrested and held in the county jail.

And there are more.

-

Michigan State University freshman Matthew Mullen was arrested for a post that read, “I’m gonna (gun emoji) the school at 12:15 p.m. today.”

-

A University of Albany football player posted a Yak in which he threatened to blow up the school.

-

A bomb threat at Corning Community College led to the evacuation of 150 students from the Perry Hall building at the New York school.

-

The University of Georgia’s Zell B. Miller Learning Center was evacuated in September after a post reading “If you want to live, don’t be at the MLC at 12:15” appeared on Yik Yak. The poster was identified and charged with two felony counts of terroristic attacks.

-

A sophomore at Indiana State University, was detained in county jail and charged with harassment after making reference to a school shooting.

-

University of Southern Mississippi student Brandon Hardin was arrested after posting a Yak that read “The red will flow tomorrow in JGH. I recommend missing class.”

-

20-year-old Velton Williams was placed on indefinite suspension and arrested after writing a Yak that indicated a “purge” of the University of Southern Mississippi campus would take place.

-

18-year-old Pompton Lakes, N.J. resident Christopher Geary issued a threat against the William Paterson University campus which sent the school into a lockdown. He was later arrested.

-

The University of Nebraska at Kearney evacuated its library after a bomb threat Yak appeared. The student who posted the threat was arrested.

-

A foreign exchange student from Spain attending St. Thomas University in Sparkhill, N.Y. was charged with generating a terroristic threat, and second-degree aggravated harassment after posting that there would be a “massacre” at the school.

-

Luis Andres Vela, a 20-year-old criminal justice major at Widener University in Chester, Penn. was arrested and had his computer seized after invoking Columbine in a Yik Yak post.

-

At Penn State University, 20-year-old Jon Seong Shim was arrested after admitting to authoring a Yak in which he threatened to shoot up the University’s HUB-Robeson Center.

-

University of South California freshman Joseph David Spencer posted “Come 3:30 this campus is going to become a very dangerous place” on Yik Yak, leading to an increased police presence on campus and Spencer’s arrest.

-

An 18-year-old at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill authored a Yak that read, “To all my friends, don’t be in the Pit tomorrow at noon. Things will be getting a big explosive.” Fischbeck was charged with making a false bomb threat.

Naturally, more and more colleges are banning Yik Yak, or at least trying to.

-

Norwich University in Vermont took steps to ban Yik Yak in September 2014 after students became the targets of cyberbullying. University president Richard Schneider told the Huffington Post, “I just know that it is hurting my students right now. They are feeling awkward, they are feeling hurt, they are feeling threatened.”

-

Utica College in N.Y. has banned the app from its wireless network and sent out emails to students warning of disciplinary actions for abusive or harassing posts.

-

In Atlanta, Emory College’s Student Government Association proposed a resolution to ban Yik Yak from the school’s wireless network. It was passed.

-

An editorial in the University of Texas-Austin’s paper the Daily Texan labeled Yik Yak as a platform for “racism, chauvinism, and negative or inappropriate feelings regarding their peers.”

-

An ongoing discussion on whether to ban Yik Yak is taking place at John Brown University in Arkansas, sparked by a fury of racial slurs and anti-Hispanic sentiments posted by students following a conference on immigration.

-

A task force has been created at the University of Montana in Missoula to deal with cyberbullying, in part as a response to combat content shared on Yik Yak, but the school’s Dean of Students suggested that he would be “very surprised” if any sort of regulation were placed on the app.

In attempts to raise awareness about the negativity and abuse that is often hosted on Yik Yak, several petitions have appeared online with the intentions of enforcing changes or outright bans on the app.

By far the most successful petition with the aim of stopping Yik Yak comes from Elizabeth Long, an 18-year-old who received personal attacks on the app suggesting that she kill herself. Elizabeth states in her Change.org petition that she attempted to commit suicide at a point in her life. She’s reached over 63,000 signatures on her petition—seeking 75,000—and has rallied the majority of that support since December.

Regardless of any attempts to put an end to Yik Yak, be it as a whole or in a community, the app will likely continue to grow. An expanded launch tour through the west coast just completed, adding users at campuses and encouraging the spread of the app through its strongest marketing tool: Word of mouth. With new backing and a big valuation, Yik Yak has overseas aspirations as well.

It’s also performed its legal responsibilities, regularly participating and helping authorities in tracking down threats posted on the app. Even that seems to not have given users any pause about how anonymous their posts truly are, an issue they should truly have concern over given the recent hack discovered by researchers that allow users to be identified.

“If this woman doesn’t stop talking, I’m going to rape her,” it read.

The app will be a part of a larger, ongoing debate over the merits of anonymity and all that it brings. For instance, Assistant Professor of Sociology at St. Lawrence University Stephen R. Barnard, Ph.D. suggests the app should be studied rather than banned.

But there should be real concern over how that conversation plays out: University of Maryland’s School of Law professor Danielle Keats Citron spoke at Duke University about her new book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. During the lecture, she talked with students about Yik Yak. She told The Chronicle of Higher Education that after the discussion had ended, a student brought their phone to Citron and showed her a post that appeared on Yik Yak while she was on stage. “If this woman doesn’t stop talking, I’m going to rape her,” it read.

Illustration via Fernando Alfonso III