We now live in a world where the Pope takes selfies. Religion, like every other aspect of our lives, has embedded itself deeply within the digital sphere.

Virtually the entire range of human expression can be found on the ‘net: People can fall in love, share works of art, go grocery shopping, try to sell artisan salamis infused with celebrity DNA—so it should come as no surprise then, that for some, faith is a far too important part of their lives to neglect online.

Increasingly, the Internet is playing host to thriving religious communities. With 25 million likes, one of Facebook’s most popular pages is the proselytising Jesus Daily, while other Christians have even developed their own social networks. There are numerous examples of religious reinterpretations of popular websites, from online dating to evangelical viral sharing sites modeled on the likes of Upworthy and ViralNova.

Together these make up an alternate social Web for the devout, embracing their faith-based identity and helping them to connect, share and even find love online with like-minded individuals.

As such, it should come as no surprise that for some communities, this digital devotion is being taking to its logical conclusion: virtual worship.

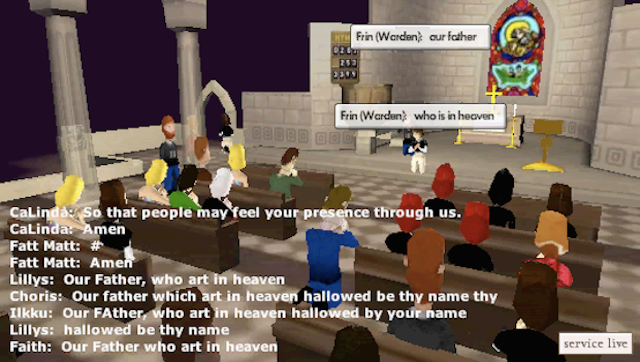

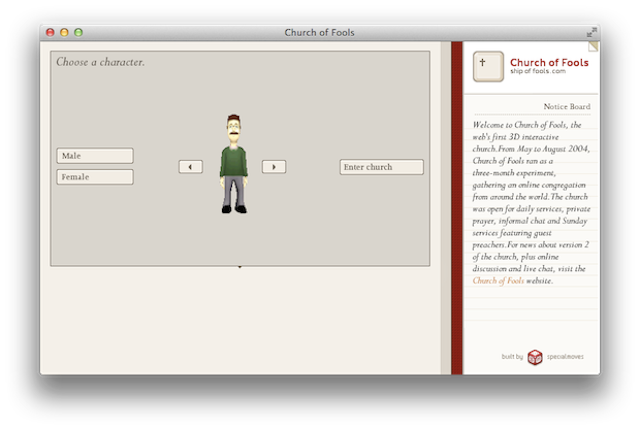

Screengrab via Church of Fools

The Church of Fools was a pioneer in the field of virtual worship. Billing itself as “the world’s first 3D interactive church,” it opened its doors in 2004 and ran for several months, holding weekly sermons as well as daily services. The church was well-received at the time, and was featured by CNN, the New York Times, and the BBC. Their formal services have long-since ceased—it was only ever intended to be a short-term theological experiment—but the chapel still advertises itself as open for private visits.

Keen to jump in, I loaded up the website and picked my avatar (the Ned Flanders look-alike seemed particularly apt)—only to be greeted with a black screen. Helpful buttons meant that I could ring the church bells and sing a rousing hymn, but any actual worship seemed off-limits.

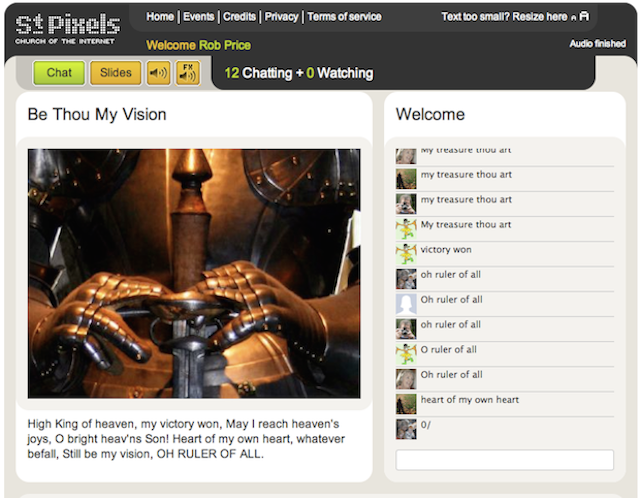

Luckily, the Church of Fools now has a new incarnation: St. Pixels. After a period of “exile” in 2005, the Church got up and running again under its new name in 2006, before migrating to Facebook in 2012.

While the original Church of Fools was run by online Christian magazine Ship Of Fools, it has since become independent. St. Pixels today is led by a disparate group of six directors, ranging in faith from Roman Catholic to Young Earth Creationist, and everything in between.

Due to the prohibitive costs involved, its 3D days are sadly long behind it. The nondenominational services now take the form of slideshow, group prayers, backing music and chat room. I was one of 12 at the Sunday evening service I attended, a decidedly low-key but strangely soothing affair.

Afterwards, the community was more than happy to hang around to talk about what drew them to St. Pixels—the answers being a mixture of alienation at physical churches, an inability to attend them due to commitments, and those who use it to supplement their visits to “real world” churches.

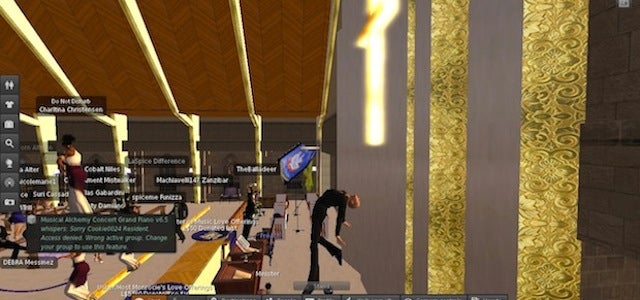

Some online faith-seekers are looking for something a bit more immersive, and that will often lead them to check out Second Life. The once-hyped reality surrogate pseudo-game is somehow still alive, and the church services it offers, visually at least, make St. Pixels look like ancient history.

We went to check out First Community Church’s weekly gospel service, one of the dozens of user-built online churches open to the public in the life simulator. There we found a packed, passionate congregation, praising Jesus’s name in a painstakingly constructed 3D virtual chapel.

While I’d hoped to discuss the intricacies of faith in the digital age with parishioners, the exact nature of their relationship with the divine will remain forever a mystery to me. A spontaneous self-crucifixion on our part led to a swift ejection from the service and removed any chance of being invited back any time soon.

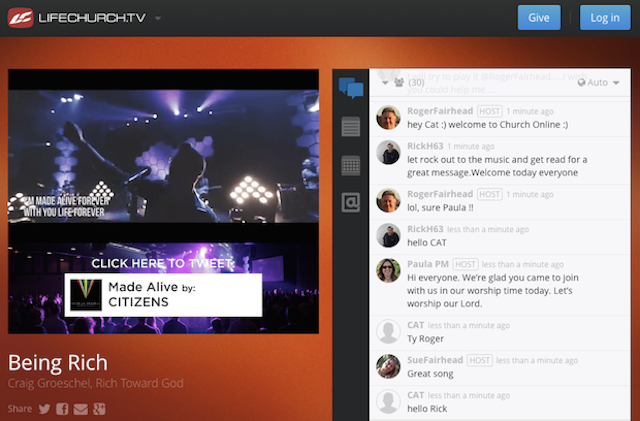

These are relatively small, informal affairs. If you’re hoping for something more in the vein of American megachurches, something a bit more corporate—you’re in luck. With 18 physical churches dotted across the United States in addition to its 50 online services every week, Lifechurch.tv is a highly polished Christ-worshipping machine, kept well-oiled by the “irrational generosity” the prominent “GIVE” buttons solicit.

By some staggering coincidence, Lifechurch.tv’s key scripture of the day was the exact same as that of the St. Pixel sermon I sat in on—1 Timothy 6. It also follows St. Pixels’ format of multimedia sermon on the left, open chat room on the right, but beyond this the differences could not be more apparent.

Where St. Pixels had stock photos and piano music, Lifechurch had a pre-recorded light show and crooning Christian rock. Where St. Pixels had an informal community, Lifechurch has designated volunteers on call 24/7, ready to “pray for Rob’s dog, that You will be there to minister all needs”.

Given its modeling on American megachurches, it wasn’t long before the inevitable call for tithes came. Spiritual richness was the name of the game, and what better way to enrich yourself than giving Lifechurch 10 percent of your annual salary?

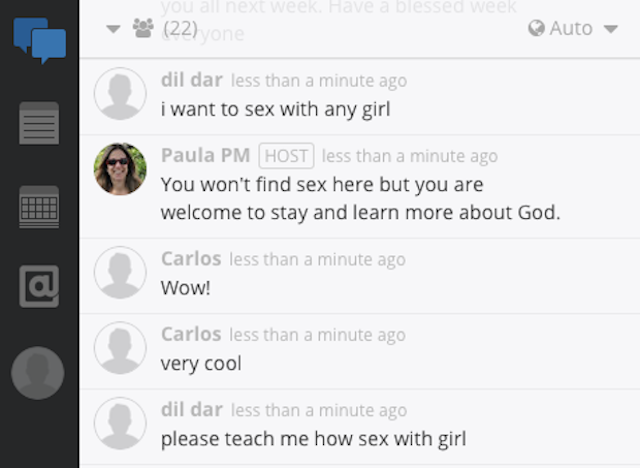

To Lifechurch’s credit, however, it had a place for everyone, even this guy:

While the fact these virtual spaces play host to worship is unquestionable. Whether they can be considered “Churches” in a more traditional sense is a trickier question for the dogma.

Rachel Holbrook, one of St. Pixel’s directors, was unequivocal about the matter. For her, a church is “a group of people trying to follow Christ; they meet for support, encouragement, teaching and prayer, but that does not need to be physically meeting up.” Though St. Pixels has yet to establish a communion service (the physicality of sharing bread and wine is a challenge given the thousands of miles separating members of the congregation), Rachel told me that she considers St. Pixels a “fully-functioning Church”.

Other virtual churches have produced their own novel responses to the Communion question, producing pre-recorded videos to bless your preferred bread and wine through the computer screen, allowing you to eat the body of Christ at your own leisure.

Others are more dubious. Tim Heaney, chaplain at the Anglican Diocese of Cyprus and the Gulf, pours cold water on the concept of virtual churches, arguing that people need to physically meet to produce a church. A building isn’t required—they can congregate “in a field or on a beach”—but they must come together to produce a church in the traditional sense.

“There is a whole theology of creation which gives importance to the physical world,” he told me, “which I think points to the importance of a church having a physical dimension.” Heaney quotes scripture in his defence, raising a definition of a church in Acts 2:42-43:

“A community of regenerated believers who confess Jesus Christ as Lord… they organise under qualified leadership, father regularly for preaching and worship, observe the biblical sacraments of baptism and Communion… and scatter to fulfil the Great Commandment and the Great Commission as missionaries to the world for God’s glory and their joy.”

Another Christian I talked to echoed this. “Preparing yourself for worship is a physical attitude,” she said. “It can’t be replicated over a computer screen.” Furthermore, she argues, they risk excluding “those who are novices to latest technologies… [or] even those who can’t communicate well through words.”

Some of St. Pixels congregation dispute this. When I posed the question to them, one responded bluntly: “have you ever been housebound?” St. Pixels codirector Rachel says an online church can help those suffering “isolation due to illness or disability, or being a carer”—but nonetheless, it’s undeniable that a church with no physical element will remain forever off-limits to some.

But what if Christianity’s not your cup of tea, though? Only 31 percent of the world’s 5.8 billion believers worship Christ after all, so statistically the majority of you reading will be offering up your prayers to other gods (or none). Luckily, there’s a spiritual home online for just about everyone.

Screengrab via Hobbypoint.in/Google Play Store

For the modern Hindu on the go, there’s the Virtual Hindu Temple Worship app. Download it to your Android smartphone phone, and you can engage in the holy Puja ritual on the metro

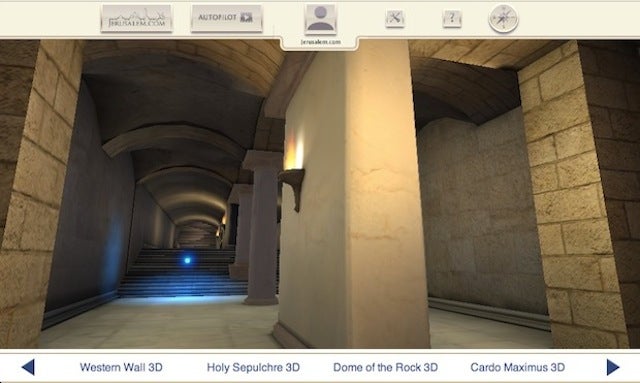

Jewish and concerned with your heritage? Jerusalem.com offers 3D virtual tours of Temple Mount as it stood 2,000 years ago. It also features the Western Wall, the Holy Sepulchre, Gethsemane, and the Dome of the Rock, so none of the Abrahamic religions need feel left out or unable to “absorb the spirituality and essence of the sites of the Holy Land.”

Beyond this however, virtual representation for Muslims is curiously lacking. Though there’s a plethora of religious resources online, there’s little to be seen by way of Islamic houses of worship in the digital sphere. VirtualMosque.co.uk seems to be one of the few sites that explicitly advertises itself as a house of worship, with weekly live streams in addition to prerecorded teachings onsite.

Second Life’s Spirituality & Belief directory lists Hindu temples, Orthodox Christian churches, Wiccan learning centres, and even secular monasteries for the nontheologically inclined—but there’s not a mosque to be seen.

If you’re the spiritual sort, however, Second Life is particularly well-equipped for your needs. The virtual landscape is littered with meditative Buddhist temples. The lack of other worshippers also makes it difficult to be accidentally sacrilegious, which is a bonus.

One game that doesn’t suffer from a lack of fellow players is World Of Warcraft. With 7 million active subscribers, the fantasy MMORPG has a total population roughly the size of Switzerland. Players often invest hundreds of hours—if not thousands—into the game, forming guilds, making friends and even getting married.

It comes as no surprise then that a game that people so emotionally invest in can be party to the spiritual side of players’ lives as well, with funerals held from time to time when beloved members of the community pass away.

It might be a sorry indictment of the state of the Internet, but the reaction from less savoury WoW players to these wakes is equally unsurprising. When a member of an Alliance guild died unexpectedly of a stroke, her guildmates decided to hold a service to memorialise her. Naively, they not only chose to hold this funeral on a public server but also to publicly disclose its location and ask politely that “nobody comes to mess things up.”

The results were, well, pretty much as you’d expect.

The forever awe-inspiring Minecraft has been the venue for a similar sombre memorial recently. Minecraft player Gas Bandit has used the multiplayer sandbox game to build a huge in-game monument to his late wife, a vast statue of a female miner modelled in her likeness.

Today, the Vatican has four times as many Twitter followers as Richard Dawkins. It’s easy to mock early Christian attempts to modernize and appear relevant to a younger audience, but we’ve reached the point where religion is as caught up in the unrelenting march of technology as any other sector of society, from leisure to commerce.

The precise dogmatic status of virtual houses of worship will vary from religion to religion, but it is also increasingly irrelevant. While their nonphysical nature means they will always remain off-limits to some, for others they can offer a spiritual and emotional lifeline.

And if some believers disapprove, then too bad, because the digital parishioners are just going to keep on worshipping without them.

Photo by Jin Zan/Wikicommons (CC BY-SA 3.0)