Jason Jones’s son wanted to learn to code. Inspired by his dad’s work in app development and entrepreneurship, the young teenager began programming after school and built his first video game in a matter of weeks. Like many other young boys, he looks to his father as a role model.

The difference is that his father learned programming in San Quentin State Prison.

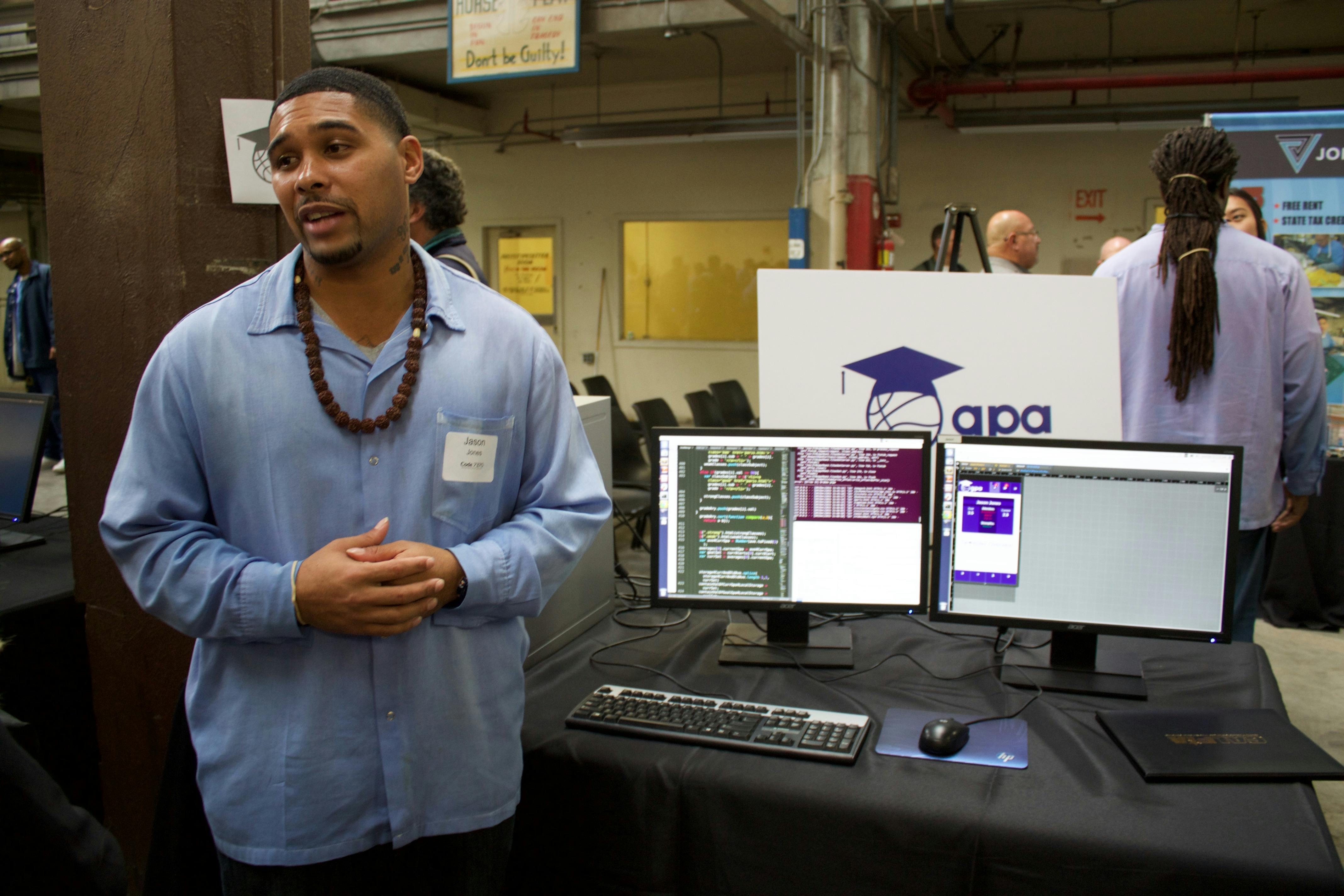

Jones is a graduate of Code.7370, a coding and technical skills development program for incarcerated individuals. He pitched his idea for his startup, Getting Parents Attention (GPA), at Code.7370’s first-ever demo day and second graduation at the prison on Dec. 9. GPA is a mobile app to help student athletes keep up with their academic studies with the support of parents and coaches. He conceived and built the app with his Code.7370 team while in prison, without access to the Internet.

“I’ve been an entrepreneur all my life, perhaps not in the right way,” Jones said in an interview. “Focusing on the social cause is more fulfilling. … Our labels of yesterday don’t define tomorrow.”

Code.7370 is a partnership with the Last Mile and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation at San Quentin State Prison that helps inmates transition into employment when they are released. The program wants to scale to facilities across the country. In Code.7370, men learn pitching techniques and coding skills like HTML, JavaScript, CSS, and Python—skills that could translate into a technical job, possibly at one of the tech companies volunteering with the Last Mile.

“I’ve been an entrepreneur all my life, perhaps not in the right way.”

Jones went through the Last Mile’s business program with the idea for GPA, and he’s one of 21 men who graduated from Code.7370. He was incarcerated in 2005, when flip phones were popular and mobile app stores were nonexistent; the iPhone hadn’t been invented yet.

Jones said it was really difficult to build an app that reflects current mobile standards and features without ever using or having access to the tech it would run on. With the help of a slew of mentors in app development and design, he and his team created a prototype that could run on a smartphone, complete with Tinder-like gestures for navigation.

Other ideas pitched by Code.7370 graduates include: Artfelt Creations, an e-commerce site to sell inmates’ artwork; Fitness Monkey, an app that enables people to break addiction through fitness; community health resource Healthy Hearts Institute; student tech program Teen Tech Hub; and Project Tycho, a collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania that visualizes public health data about vaccines.

Technical skills are just one aspect of the program. Jones said the Last Mile’s Beverly Parenti improved his grammar and reading, and cofounder Chris Redlitz helped him with impulse control and preventing negative reactions to certain situations.

Jones hopes he can turn his app into a thriving startup when he is released in 2017. He’s one of many program participants who wants to take his skills beyond the prison’s walls and into Silicon Valley. But it’s hard for anyone to achieve startup success, and the difficulties are compounded for a person of color who spent over a decade behind bars.

A step forward

The Last Mile was founded in 2010 by Silicon Valley venture capitalist Chris Redlitz and his wife, Beverly Parenti, who serves as executive director. Because of the organization’s close Valley ties, a number of prominent tech luminaries, investors, and programmers have visited with the program’s incarcerated participants. Hip-hop megastar and venture capitalist MC Hammer is on the board of directors and was a special guest at the demo day event, and in October, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg spoke to the Code.7370 class.

For the last five years, the Last Mile has taught entrepreneurship skills through TLM Business, the precursor to the Code.7370 program. In the business program, individuals develop startup and app ideas, and the men in Code.7370 build the apps and create websites using ideas based on the TLM Business projects. Entrepreneurs in the business program rely on books and lectures to learn about business models, Web design, and social media. Code.7370 students use a computer program that simulates live coding, as Internet access isn’t permitted.

Ten graduates of the Last Mile have been released from prison, and James Houston and Heracio Harts, two graduates who have been out of prison for a couple years and are working on startups in the Bay Area, spoke at Wednesday’s demo day; teams from Code.7370 built and pitched their corresponding websites.

Thanks to the media attention the program has received, especially after Code.7370’s launch in November 2014, many people may consider the Last Mile to be an on-ramp to working in tech in Silicon Valley, where sky-high salaries and young white programmers make up the Bay Area stereotype.

Some tech companies work with the Last Mile directly to hire graduates from the program upon release, including RocketSpace, a technology campus and startup office space in San Francisco. RocketSpace has hired three graduates since 2013. In 2012, CEO Duncan Logan met Crisfino Kenyatta Leal at the Last Mile’s demo day and offered him a job on the spot upon release. Leal is now the company’s manager of campus services and one of the most well-known program graduates.

“Like any new employee, there is a learning curve. Usually, things that can be easily taught like how to use internal communication platforms or culture and processes,” Logan said in an email. “The Last Mile graduates that we’ve hired arrive with characteristics that you can’t teach: determination to succeed and a commitment to make a difference.”

Harts and Houston chose to pursue their own startup projects that give back to the communities they call home over the sleek startups or tech companies that pervade the Bay Area. (None of the Last Mile graduates have successfully received venture funding, Harts said.)

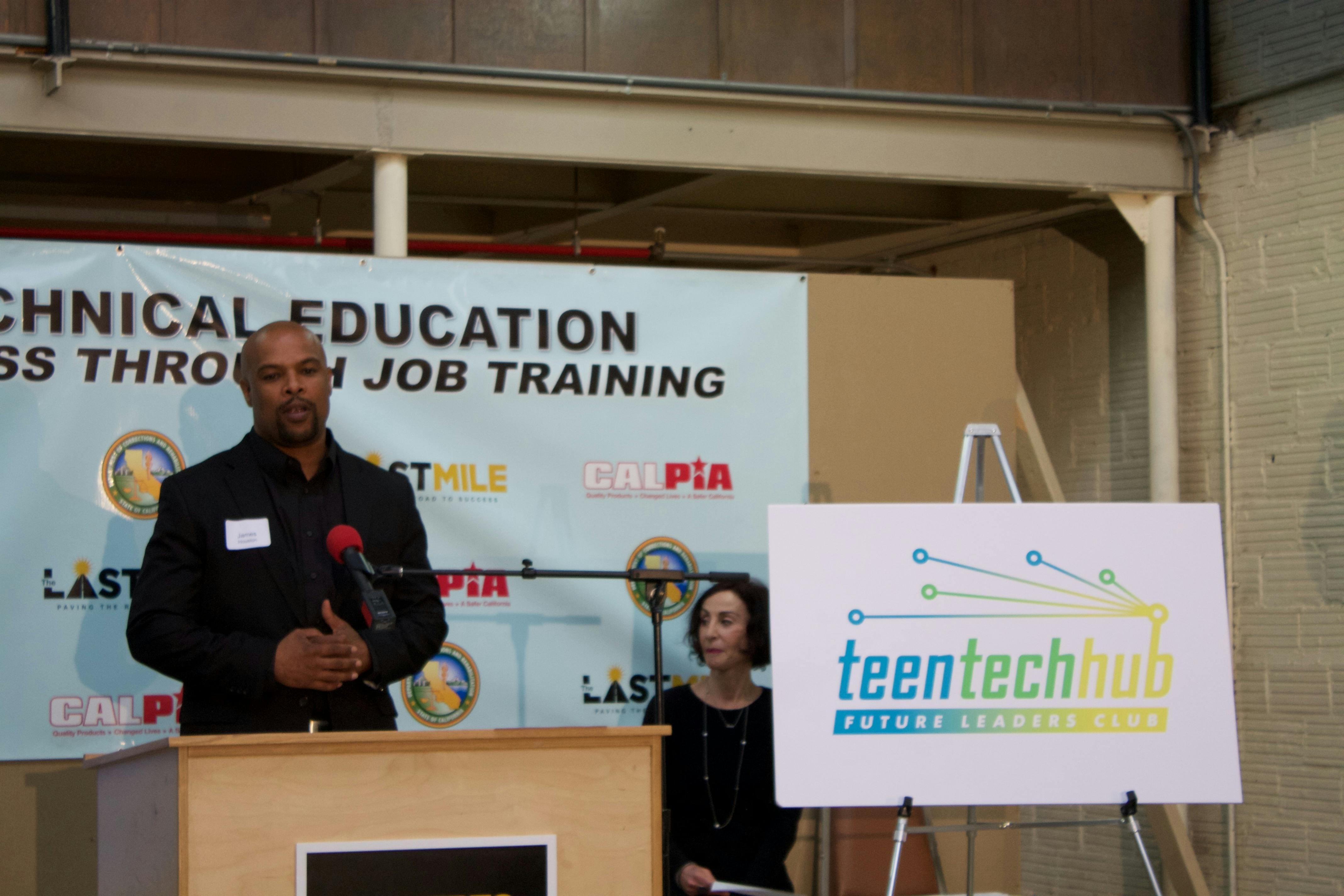

Houston founded Teen Tech Hub at TLM Business while he was still in San Quentin State Prison. The 42-year-old served 18 years for second-degree murder. He declined to speak to me about his conviction, but on Quora, where he answered numerous questions about incarceration and the Last Mile, his profile reads: “The absence of a father figure and being the oldest played a major role in my gravitating to the street life and selling drugs. This ultimately led me to indirectly taking the life of another human being which I am incarcerated for now.”

I sat down with Houston in a conference room at the City of Richmond offices in Richmond, California, before December’s demo day. Houston is the head of outreach at the Office of Neighborhood Safety in Richmond, and he gives intensive mentorship and support to at-risk individuals, such as those who might break the law through violence or drugs.

Teen Tech Hub will be an after-school program for inner city youth ages 9 to 14, providing technical training, personal guidance, and computer literacy skills. The City of Richmond plans to support the program, and Houston is hoping to partner with coding organizations in the Bay Area to provide the curriculum. He pitched the idea, and the Code.7370 team demonstrated a completed website they built behind bars. Steve Lacerda, the team’s technical lead, presented an interactive game made for the site, which he named after his daughter.

“I had ideas of what I wanted to do, but I never really thought it would become a possibility,” Houston said, referring to his initial introduction to the Last Mile.

Students will benefit tremendously from educational resources that teach technical training not found in classrooms. In the West Contra Costa Unified School District that encompasses the City of Richmond, just two out of 10 high school and alternative education institutions offer AP computer science courses, according to the school district’s accountability report cards. Through Teen Tech Hub, Houston will provide the opportunities to students that he didn’t have before going to prison.

From prison to the startup life

Houston pitched the idea for Teen Tech Hub at a TLM Business demo day back in 2012. At the time, reports said Last Mile co-founder Chris Redlitz had secured space for the program, and Houston had support coming from organizations like Teens in Tech. But years later, Teen Tech Hub remains a passion project without a permanent home. Houston told me there are plans for it to be in one of Richmond’s recreation centers, though the exact location is not nailed down yet.

When he was released in mid-2013, Houston got a job as an intern at Ribbon, a payments startup located in San Francisco. Listening to Houston’s experience navigating the startup world after spending almost two decades incarcerated just an hour’s drive away was illuminating. The culture might seem weird and isolating even for those of us who live and work in it, but perception shifts significantly for someone who was in prison for almost two decades.

“I was surprised because so many people don’t talk to each other now.”

“The part that was difficult is coming to not just the tech industry, but going to a startup, was going in there and the CEO is 27 years old,” Houston said. “I’m old enough to be the father of the oldest person in there. So that brought up a lot of regrets. Like, if I would’ve stayed focused, and thought about the possibilities of what my life could’ve been.”

Houston was on the business team at Ribbon and worked with onboarding users, writing blog posts, and helping to redesign the layout of the website to make it more user-friendly. After seven months at the company, Houston decided to leave the desk job and work with people instead, at a place where communication wasn’t exclusively through messages and email.

The way communication had changed in the workplace and in personal relationships was something Houston did not expect.

“I was surprised because so many people don’t talk to each other now. I used to always wonder why people text instead of call. It was always texting or emailing,” he said. “You don’t talk anymore the way they used to. A lot of stuff can get misunderstood by a person who is reading a text depending on where they’re at in their life or what they’re going through.

“[At Ribbon], we were all in this room together, but we were chatting [online] … That part was weird. We’re right across the room, I could just be like ‘Hey!’ and instead we’d send a message.”

Though Houston’s experience as being the only former inmate at a startup is relatively unique, there was another way he was different from those working around him: Houston was the only African-American at his company. Connections and participation in the Last Mile program gave him opportunities to pursue new career options when he was released, but they didn’t prepare him for the culture he would be working in.

In Silicon Valley, tech companies are largely white and male, and though startups and corporations are trying to improve diversity, people of color are largely underrepresented. At Google, for instance, just 2 percent of the U.S. workforce is black and 3 percent is Hispanic; in tech roles, those numbers drop to just 1 and 2 percent, respectively.

The Code.7370 demo day neglected to acknowledge this disparity. The pitches and apps built with no Internet access were impressive, but the surrounding discussions sharply contrasted with the realities of working in the tech field.

On stage, Parenti said: “In this industry, you are judged by the quality of your code, not by the stigma of your past.”

The technocratic idealism was met with applause and nods from the audience, who seemed to forget that the tech industry’s meritocracy myth has been debunked many times over.

Time and again, data demonstrates that success is not just about engineering abilities. Company leaders say they have to “lower the bar” to find diverse technical talent; they blame the “pipeline” for a lack of people of color in tech despite graduation rates greater than companies’ hiring percentages, and they invest in initiatives that only impact one group of diverse employees.

When I asked Parenti to clarify the statement with regards to inequity in tech, Redlitz replied via email:

Bev was referencing the opportunity in the future [regarding] outsourcing development work to the prison, instead of outsourcing overseas. Many companies who use outsourcing don’t know or have full context of the developers who are doing the work, they are judged by the quality of their work.

According to USA Today, inmates may soon earn up to $20 per hour with coding through a nonprofit called Turn2U Inc., which was created by Redlitz and Parenti. But there is limited information publicly available about the proposed initiative.

Houston said that people at Ribbon tried to make him feel welcome, but he still felt like an outsider.

“I start thinking I’m here because of the help of someone, then thinking about my background, then thinking about the race as well. It did kinda make me think about white privilege,” he said.

“Understanding from the point of view of what I understand now, I can cope with it better. But thinking about so many young people, like if they had access to some of the things that [others] had access to, where would they be?”

Access and education is exactly what he wants to provide to kids in Richmond, so they won’t have to ask themselves: “What if?”

Flying solo

While Houston is bringing technology education to his hometown, Harts is making his community healthier. Harts founded the Healthy Hearts Institute after serving over eight years in prison.

Harts told me about his passion for healthy living and improving community wellness between personal stories of laughter, struggles, and successes at a Starbucks in Dublin, California, the “office” where he works on building his company.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, healthy eating and physical activity have a direct influence on students’ academic achievement and, in turn, help support and contribute to more successful communities overall. By providing access to resources for healthy foods and lifestyles, Harts wants to create cultures that foster health and nutrition, and eventually change the way fitness and health clubs operate.

At the Code.7370 demo day, the Healthy Hearts Institute team unveiled a new website, with parallax scrolling, a new blog and volunteer pages, and an inspiring video featuring Harts in his community.

Harts worked in sales and business development at two startups before fully committing to the Healthy Hearts Institute. He also drives for Uber and told me that by driving tech guys and their friends around, he began to understand how much fraternities and connections play a role in building companies and hiring new talent.

“Yeah, you’re giving someone this opportunity, but are you really invested in them?”

“I don’t want to generalize it … but I didn’t feel like the [tech] community was geared toward me to be successful,” he said. “There were other people in the same position that had easier ways to be successful. It just didn’t seem like it was built for me.”

Harts said it was a regular occurrence to go to a networking event with a colleague and be the only African-American in a roomful of white and Asian techies. And while his company tried to be inclusive, the conversation at the events he attended just didn’t flow the same as it would had there been more attendees of color.

You have to feel comfortable being the odd one out, he said, and it would have been helpful if the Last Mile had prepared him to be the only African-American in the room.

Harts described a feeling of being on the receiving end of a hand-out.

“A lot of times people who have been released back into society are told they’re being given a second chance,” he said. “But if you grew up in the projects, in a violent culture, with lots of drug use, high stress levels, and the school system is jacked up because public schools are underfunded—when did you get your first chance?

“Yeah, you’re giving someone this opportunity, but are you really invested in them? Saying here’s your chance, you can learn on the job, we’re paying for healthcare. We are going to help you every step of the way. That’s something different.”

Starting his own company was an obvious choice for Harts, but not an easy one. Venture capitalists and technologists generally aren’t investing in communities like his, he said, and it gets even harder to secure funding having been to prison. Already African-American entrepreneurs are at a disadvantage—according to one widely cited report from CB Insights in 2010, just 1 percent of venture capital-funded startup founders are black.

“Part of me says I’ll change [the tech culture]; I’ll be the person that breaks the barriers,” he said. “But part of me says, my time is better spent focusing on my own passion project than to take the lead and make these differences. Maybe that’s for someone else to do.”

Since leaving the Bay Area tech scene, his drive and vision to pursue his own social good company is paying off.

The Contra Costa County Housing Authority granted Harts permission to build a community garden in the Pittsburg, California, projects where he grew up. The 1.5-acre property will be home to 10 to 15 plots of gardening land for residents, and the rest will be used for farming things like eggs and honey. He is working on obtaining a lease agreement for the property.

“I have a verbal agreement in place with the director of nutrition services for the Pittsburg Unified School District to purchase produce from the garden,” Harts said. “I hope to have a weekly farm stand located at the garden site.”

The future graduates

Whether or not the Last Mile is successful depends on how you define success. Although none of the returned citizens from the Last Mile program have received venture funding, and not all of them have continued on in the tech field, the supportive community the men found and built through the program has followed them to life outside prison.

Houston said he goes on hikes with people and their families he met through the Last Mile, and both Houston and Harts occasionally meet with Redlitz.

From Jones’s perspective, Houston, Harts, and other graduates are a testament to the success of the Last Mile, even if their startups fail. And his son’s new interest in computer programming demonstrates an indirect impact the program is having beyond teaching skills to the incarcerated.

“They paved the way for us—they set a good name for every graduate out there,” Jones said. “No longer are we ex-felons. We are now graduates of the Last Mile.”

Photos by Selena Larson