It’s become predictable: If you witness a tragedy and tweet about it, a reporter will contact you. And then the rest of Twitter will respond to the eager journalist with some variety of “you are a bottom-feeding piece of shit.”

The latest instance of bandwagon reporter-hate happened yesterday, after a gunman opened fire at Lone Star College in Texas, injuring three. Just a month after the horrific mass shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., which left 28 dead (including 20 children), it’s no surprise the Sauron’s eye of national media immediately swung its focus to the Houston-area college.

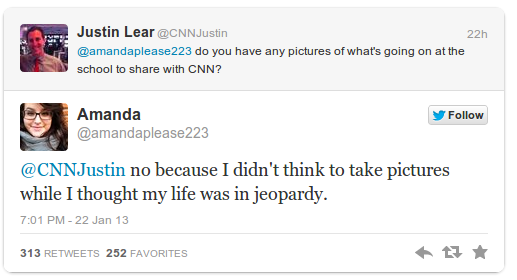

One Twitter user who witnessed the event, whose first name is Amanda, cowered in a classroom as the gunshots rang out through her building. After getting out—and home—safely, she tweeted about what she’d seen.

Almost immediately, CNN national news editor Justin Lear reached out to her, asking if she happened to snap any pics. Amanda’s response became a kind of viral hit.

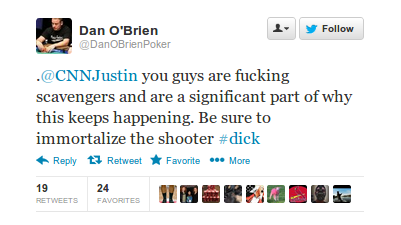

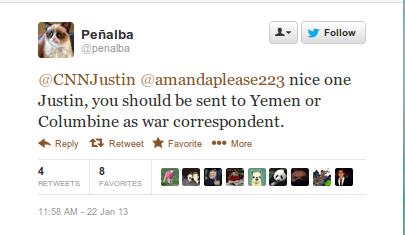

The rest of Twitter didn’t much appreciate Lear’s request, either.

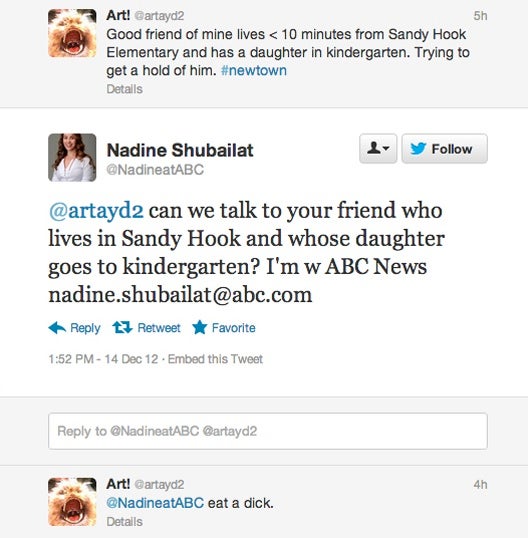

The outrage is reminiscent of what happened to Nadine Shubailat, an ABC News reporter who reached out to a family friend of one of the Sandy Hook shooting victims the day of the massacre.

The flood of hate on Twitter was so overwhelming that Shubailat deleted her account.

Reporters have been doing this forever of course, though usually with a knock on a door or a phone call. In those days, the understandable “screw off”s from angry, emotional victims stayed more or less private. The reporter walked away, and the event was forgotten.

Some of the people deriding CNN’s tactics on Twitter probably also tune into cable news when tragedies like this happen, eagerly lapping up each drip new information that “bottom-feeding” reporters produce.

Sure, reporters do go too far, hounding family members and victims to get a juicy quote. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with reaching out to eyewitnesses after a tragedy. It’s sometimes the only tool journalists have to fill out a timeline of events and to understand what really happened. When it’s done right, it serves a valuable public service. Some witnesses actually want their story told.

Writing on the pushback against Shubailat, Poynter’s Jeff Sonderman noted that Twitter doesn’t just make reporting public, it strips any sense of emotion or sympathy from a reporter’s inquiries. Delicacy is tough in 140 characters or less:

While social networks have made it easier for journalists to find and contact potential sources, it’s also made the hardest part of the job even harder. Those delicate interactions, what used to be just two humans figuring out what feels right, often occur over the cold distance of electronic communication and in full view of the public.

It’s even harder when the public’s faith in journalists is at an all time low.

Photo by andorand/Flickr