There was something about the sudden, near-universal praise for police body cameras that rubbed Seth Stoughton the wrong way.

A law professor at the University of South Carolina who has spent his career studying the regulation of law enforcement, Stoughton saw the potential of equipping thousands upon thousands of American police officers with cameras recording their every move as one of the most important developments in his field in at least a decade. But he was skeptical.

Reforming the criminal justice system, especially in terms of the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities, has been a major topic of political discussion in recent years. Much of that is due to an explosion in on-the-ground, amateur surveillance. When a cop in South Carolina fatally shot Walter Scott while the 50-year-old was running away, clearly posing no immediate physical threat, it sparked a national outcry and the indictment of the officer, Michael Slager—but only because a bystander, Feidin Santana, whipped out his phone and filmed the encounter.

Pushed by social media-fueled movements like Black Lives Matter, the conversation in Washington gradually pivoted from political grandstanding about being tougher on crime to politicians proposing bipartisan solutions for criminal justice reform.

If phone cameras could inspire reform by capturing instances of cops behaving badly, keeping a comprehensive record of everything done by every police officer across the country could go even further in ensuring those officers treat the communities they serve with the respect those communities have demanded for generations.

A year-long study of body-worn camera use in the small Southern California city of Rialto showed that department-wide implementation of body cameras decrease police use of force by 65 percent. Civilian complaints against officers dropped by 88 percent. Another study, this one conducted in Orlando, Florida, produced similar results. Use of force incidents for officers wearing the cameras dropped by half compared to those without them. Civilian complaints decreased by two-thirds. The officers themselves reported significantly fewer injuries because civilians, cognizant they were being recorded, were less likely to do something stupid.

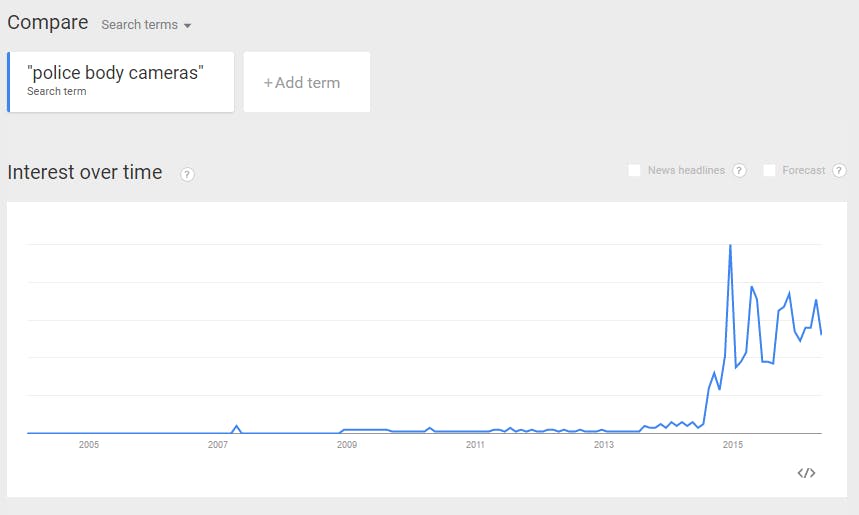

Public interest in body-worn cameras, as evidenced by Google search queries, skyrocketed.

Talk of a nationwide roll-out of body-worn cameras drew praise from across the political spectrum. The American Civil Liberties Union called the cameras “a win for all,” and the law enforcement community, often skeptical of solutions pushed from outside the thin blue line, was generally supportive. “It’s proven the guilt of suspects 100 percent of the time, and the [district attorney] loves it,” one officer wrote in a post on the social news site Reddit. “Every complaint has been found baseless and made-up, or they were mad they got caught and thought making a complaint would help them. No police officer should go without wearing a camera.”

In late 2014, President Barack Obama announced a three-year, $263 million grant program funding police body cameras through the Justice Department.

Police body cameras are held up as a panacea, a technical solution to much of what ails the criminal justice system. But beneath the hype, experts say, police body cameras may exacerbate an inherent, inescapable bias that stands to have broad consequences for the future of justice in America.

“I started paying attention to the calls for body cameras, and it seemed to me that almost everyone on every side who was calling for body cameras was doing so with more enthusiasms than perhaps was warranted,” Stoughton said. “To say I was skeptical would be putting it lightly.”

Stoughton had heard this tune before: The faults of America’s criminal justice system could be patched up with flashy new gear. In the 1990s, departments across the country installed dash cameras in police cruiser as a way to deal with a rash of accusations about racial profiling. If the Department of Justice’s report on the systemic ways the police department in Ferguson, Missouri, preyed on the city’s African-American population is any indication, the root of the problem ran much deeper than whatever crevasse dash cameras could weed out.

“We can find this pattern, unfortunately, throughout the history of police reform. … [It’s] something that happens in society generally: We all like the next thing,” Stoughton said with a sigh. “Quite frankly, the idea of a simple answer is really attractive. The idea of just slapping cameras on officers and everything will be better is a really, really seductive idea. But unfortunately, it turns out to be, I think, a mistaken one.”

Stoughton is part of a growing chorus of academics who, while all generally singing the praises of body-worn cameras, warn that a whole host of cognitive biases present in each and every one of us have the potential to dramatically affect what lessons we derive from footage captured by these cameras. Video cameras, they warn, present the illusory promise of obtaining a fleeting glimpse into the objective reality of every interaction between police officers and the civilians they are tasked to protect and serve. But the way our brains are wired turns any hope of true objectivity into an impossibility. Unless those biases are understood and controlled for throughout the criminal justice system, our constantly recorded future could be just as unfair as the present it aims to replace.

“The same person can watch the same event with a different camera angle and view the facts differently. That’s particularly worrisome.”

For Drexel University law professor Adam Benforado, the problem is one of faith.

Last year, Benforado published a book called Unfair, a deeply unsettling look, based on decades of psychological research, at the litany of ways our fallible human minds transform even the best-intentioned parts of the criminal justice system into exercises in the monstrously arbitrary. For example, as Benforado recounts in the book, judges are significantly more likely to award defendants lighter sentences earlier in the day, or if they’ve just come back from having lunch, due to the mental exhaustion of having to make decisions all day.

“When we are trying to figure out what happened … videotaped evidence is better than no evidence. Unfortunately, we’re just so convinced that video tape offers this direct view back in time that we ignore the potential for bias,” Benforado told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. “That’s one of the most dangerous things in using videotape. We think we don’t need to be skeptical at all—that it’s safe to just relax and think, ‘this is just reality.’ It’s as if we’re standing on the street corner watching what happened. … And that’s just not true.”

“Two different people with different background can watch the same videotape and see different things,” he continued. “But the same person can watch the same event with a different camera angle and view the facts differently. That’s particularly worrisome.”

Benforado’s concern about camera angles relates to a phenomenon called camera perspective bias, which is how the placement of a camera can have a dramatic effect on how viewers perceive the captured events. In essence, our brains tend to adopt an interpretation of video that is favorable to whomever perspective we are sharing.

In 1975, researchers Shelley Tayor and Susan Fiske conducted an experiment where they showed subjects recordings of a conversation and asked them to rate how much influence each of the two participants had over the interaction. When viewers saw footage from the perspective of Participant A, looking at Participant B, they were more likely to ascribe more influence to Participant B. When the direction of the camera was flipped, so did their judgment of who exerted more influence—even though both groups were watching the exact same conversation.

By visually putting themselves into the shoes of one participant or the other, viewers reflexively became more sympathetic to the person whose “eyes” provided the experience of the world, which has the effect of making everyone else seem more aggressive.

Those results were replicated in series of similar experiments led by Ohio University professor G. Daniel Lassiter, which applied the consequences of this phenomenon to a law enforcement setting. In 1986, Lassiter filmed a mock interrogation resulting in a confession from a trio of different angles—one facing the suspect, another facing the interrogator, and a third with both parties equally positioned in the frame. Viewers were then asked if they believed the interrogator obtained the confession through coercion.

Lassiter found that people who watched the scene from the suspect’s perspective were significantly less likely than those who saw it from the interrogator’s point of view to rate the confession as involuntary. People who watched the video from the neutral perspective said confession was coerced at the same rate as the subjects who only listened to an audio recording or read a written transcript of the conversation.

Subsequent experiments showed that—not only did this camera perspective bias effect hold for suspects accused of a range of crimes, from burglary to drug trafficking to sexual assault—it also affected perceptions of the likelihood of a suspect’s guilt and sentencing recommendations. Moving the camera from an angle showing both parties equally to one with just the suspect in the frame doubled the likelihood viewers of the video would convict the suspect.

Giving people more time to deliberate between watching the video and making their assessments did not reduce the influence camera perspective bias had over their responses, nor did explicitly urging them “to concentrate on the content of the confession, rather than the manner in which it was presented,” the researchers found.

When Lassiter repeated the experiment with 21 judges who had previously served as either prosecutors or criminal defense attorneys and two dozen law enforcement officials with extensive experience conducting suspect interviews, the result was the same. A career spent considering the mechanics of police interrogations was little defense against the tricks the camera plays on the human brain.

Research into the broad effects police body-worn cameras on the criminal justice system is a rapidly expanding field. To Stoughton’s knowledge, however, no one has specifically looked into body-camera perspective bias. However, previous research suggests this bias could affect body-camera footage. Affixed to the chest or glasses of a police officer, police body cameras inherently capture the cops’ perspective, thereby systematically biasing viewers of that footage in favor of the officer.

This bias can also work in the other direction, and likely already has. When a bystander is filming a police officer with a cellphone camera, and the officer is addressing the videographer directly, research suggests the officer’s actions are going to appear more aggressive than if the film was taken from a third-party perspective.

Take, for example, this video of an NYPD officer in the midst of wrestling a suspect to the ground and pointing his gun at a videographer in a New York City subway station.

The officer, who also got into a physical altercation with a civilian while leaving the station following the incident, was stripped of his badge and gun. By watching the video—thereby stepping into the shoes of the videographer—you’re effectively having a gun pointed at your face, which is legitimately unsettling. The officer appears needlessly aggressive. However, video taken from the officer’s perspective would almost certainly show a scene that felt very different.

The point here isn’t to argue whether the officer’s actions were reasonable in the moment, which is the legal standard for determining the acceptability of a police officer’s actions. Rather, it’s to show, even in instances where video of a police interaction may appear to tell the whole story, there’s reason to have some skepticism.

The location of the camera on the officer’s body matters, too. In the United Kingdom, where police have used body-worn cameras for the better part of a decade, the majority are mounted at head-level—on officers’ glasses. In the U.S., the preferred position is on the officer’s chest. The height differential can made a big difference.

“Imaging you’re standing face-to-face with someone about your height. You’re looking at approximately their eye level, your shoulders are about the same level as your shoulders are. You’re physically about the same size as this person,” Stoughton explained. “Imagine that they stay standing, but you bend you knees and you put your eyes where your chest was when you were standing up. All of the sudden, the other person looks totally different, they look much taller. And maybe, depending on stance and angle, maybe their shoulders look broader. They look scarier now.”

The idea that camera positioning can have a significant effect on the emotions evoked by a video isn’t a recent revelation. Filmmakers have been toying with camera angles for generations. When Peter Jackson wanted to make the hobbits of the Lord of the Rings movies look short in comparison to the other races of Middle Earth, he primarily used camera-angle tricks and forced perspective rather than CGI wizardry.

In his seminal 1973 short film No Lies, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Films, director Mitchell Block used first-person perspective to depict a man interrogating a woman about being a survivor of a sexual assault. The film was shot with a body camera taken from the man’s point of view. As the man’s interrogation becomes intense and accusatory, the film becomes a pointed commentary on how society trivializes women’s experiences of sexual violence. The camera perspective implicates the viewer in that trivialization because there’s an automatic reflex to identity with the man wearing the camera. Block’s skillful use of camera perspective bias is an essential element in what makes No Lies such a powerful indictment of cultural misogyny. As viewers, we feel like we’re, in a sense, one with the cameraman, even when the cameraman is being a callous jerk.

Yet, Block insists, when looking at real-life footage captured by something like a police body camera, that intimacy is an illusion. “The difficulty in looking at those images is that, while we’re seeing an objective reality of what is being recorded, we aren’t seeing or understanding what’s going on in the head of the person on whom the camera is mounted,” he told the Daily Dot. “That’s what creates the problem.”

A career spent considering the mechanics of police interrogations was little defense against the tricks the camera plays on the human brain.

Police body-cameras aren’t going away, nor should they, experts say. These cameras have proved an effective tool for both law enforcement and activists dedicated to watching the watchmen. They key is to ensure these biases are actively acknowledged and to build safeguards into the process to help people in positions of power throughout the criminal justice system control for them.

The simplest solution is to, whenever possible, use footage taken from a third-party perspective. In New Zealand, neutral perspectives in videos of interrogations are mandated by law.

When it comes to body-camera footage, video taken from a third-party perspective is often not available. Here, Benforado presents a number of options:

-

Categorically prohibit the introduction of body-camera footage into evidence

-

Leave the decision of whether to allow body-camera footage up to the defendant

-

Only bringing in body-camera footage if there is also other video of the incident taken from a different perspective (such as a bystander’s cellphone or the squad car’s dashcam)

-

Bring in experts to inform juries about camera perspective bias

-

Require judges to include a discussion about camera perspective bias in jury instructions

While Benforado believes an across-the-board exclusion of body-camera footage is a defensible position, he admits it’s unlikely to appeal to a broad cross-section of Americans—meaning a more balanced approach has a better chance of becoming the norm.

These types of considerations are crucial during trials, but they’re also important to keep in mind during all of the other places throughout the criminal justice system where body-camera footage is used but lacks the same level of evidentiary standards that exist in a courtroom. Footage from body-worn cameras is used in officer training; it’s reviewed by officers as they fill out paperwork after a day’s shift; it’s used by departments’ internal affairs divisions to assess officer conduct; and it’s reviewed by criminal investigators to determine whether or not to file charges against the suspect (or, in some cases, the officers themselves).

Conversations about how to account for bias in viewing body-camera footage are starting to happen. Dr. Michael White, a criminology professor at Arizona State University with experience studying these issues, has received funding from the Justice Department’s police-body-camera grant program to work with law enforcement agencies in determining the best methods of implementation.

“It’s an extremely complex undertaking,” White told the Daily Dot. “There are a lot of moving parts. There are lots of opportunities for departments to do this poorly. And, I think, the recognition of the complexity is really what’s driven the research.”

For his part, Stoughton sees cognitive biases like this one as akin to a pair of tinted sunglasses you’ve been wearing for your entire life. You may be seeing the world in a slightly orange hue, but really your perception is distorted. The key, he argues, is to never forget what’s sitting right on top of our noses.

“Knowing about the potential for bias is very different than not having it,” he said. “There is no way to get around the fact that we all have these cognitive biases. We don’t think we do. We think that we are capable of being perfectly objective, neutral arbiters of fact, but that’s because we can’t see the tint of the lenses that our brains have.”