Late last month, Syrian users of the massive open online course (MOOC) provider Coursera were met with an unpleasant surprise when they attempted to log in. Instead of being able to access hundreds of online courses (like Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Shiller’s class on financial markets or a primer about the basics of electrical engineering) they were turned away.

They got a notification saying that, because they lived in a country subject to economic sanctions from the United States, American MOOCs were prohibited from helping them learn.

Reaction to the blockage among Syrians who regularly used Coursera was predictably negative.

“This really bad for us,” Ahmad Sufian Bayram, the lead organizer for Startup Weekend Damascus told the Middle East-focused entrepreneurial news site Wamda . ‟[Thanks to the current conflict,] most people cannot go to universities, and cannot take extra courses, so we look to free online courses to make up the difference. We rely on these courses for knowledge, to learn how to become entrepreneurs.”

‟Certain United States export control regulations prohibit U.S. businesses, such as MOOC providers like Coursera, from offering services to users in sanctioned countries, including Cuba, Iran, Sudan, and Syria,” wrote a Coursera spokesperson in a blog post explaining the policy. ‟Under the law, certain aspects of Coursera’s course offerings are considered services and are therefore subject to restrictions in sanctioned countries.”

The ban had not been previously implemented because there was some confusion over whether MOOCs fell under the rubric of services U.S. organizations were prohibited from providing to sanctioned countries. Coursera has said it only changed its policy after being informed by government officials that its operations in sanctioned companies were in violation of the law.

A few days after the initial outcry, Coursera backtracked, admitting they were incorrect in banning Syrian users, because—at least in the case of Syria—the law contains a loophole allowing for U.S. groups to provide educational services. The move was a victory for MOOC advocates who believe educating the populace is one of the best weapons against repressive regimes. However, it highlighted the fact that there are still a handful of other countries (such as North Korea, Sudan and Iran), where the ban is still being enforced.

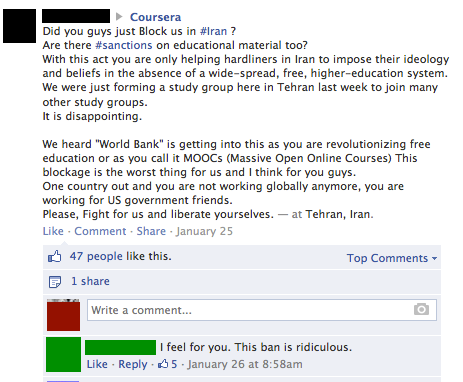

Some of Coursera’s Iranian fans took to Facebook to express their anger:

Coursera insists it is working with the U.S. State Department to find a way to reinstate its services in sanctioned countries. ‟The Department of State and Coursera are aligned in our goals and we are working tirelessly to ensure that blockage is not permanent,” the company explained in a blog post.

That anger is also shared by some of the professors who whose classes are being distributed through Coursera. In an email sent to blogger Joey Ayoub, Professor Ebrahim Afsah of the University of Copenhagen slammed the U.S. government for preventing Coursera from distributing his class on Constitutional Struggles in the Muslim World:

Dear All, I write this email under protest and with a considerable degree of anger and sadness. Few things illustrate the bone-headedness, short-sightedness, and sheer chauvinism of the political structure of the United States better than the extent to which its ideologues are willing to go to score cheap domestic political points with narrow interests in the pursuit of a sanctions regime that has clearly run its course.

But you will now be interested to hear that also my course (and anything else Coursera offers) has been classified, if not a weapon that could be misused, then at least a “service” and as such must not fall into the hands of anybody happening to live in the countries that the United States government doesn’t like. I have thus been informed that my students in Cuba, Syria, Sudan and my homeland will no longer be able to access this course. I leave it to you to ponder whether this course is indeed a weapon and if so against what and what possible benefit the average American citizen could possibly derive from restricting access to it.

Nearly 100,000 people have signed an online petition urging the White House to allow MOOCs to include students from sanctioned countries. ‟By including…[MOOCs] within the definition of services which cannot be provided to citizens of sanctioned nations, America sends a message that these values are not universal, and that America will decide which of the world’s citizens can participate and which cannot,” reads the petition. ‟School is in session. What will the lesson be?”

These restrictions aren’t being applied universally to all MOOCs. EdX, an online educational platform created as a partnership among American research universities including Harvard, M.I.T. and U.C. Berkeley, successfully applied for an exemption allowing it to operate in Iran and Cuba. The organization is reportedly holding off on issuing certificates to people in those countries who have completed courses until it gets further clarification from the U.S. government.

However, as Afsah advocated in an email to his students, the best way to for students in the sanctioned countries to access American MOOCs is to use a virtual private network (VPN) to skirt the restrictions entirely by disguising their location.

H/T Inside Higher Ed | Photo by strngwrldfrwl/Wikimedia Commons