When the copyright holder discovers a video on YouTube using their content without permission, they can petition Google to have the video taken down. This process is what keeps most of Hollywood’s latest releases from popping up on the massively popular video sharing site they moment they come out. That process can be abused, however, by people who simply want to censor embarrassing or critical videos—videos that aren’t actually violating anyone’s copyright.

According to San Francisco-based housing activist Jackson West, that’s precisely what happened to him earlier this month when a video he took of anti-eviction protest was taken down as a result of a copyright infringement claim by the protest’s target. West detailed his experiences in an article published in SF Appeal.

Starting late last year, the law firm of Bornstein & Bornstein began hosting a series of ?boot camps” for landlords in San Francisco. Being a landlord in the city isn’t easy. Most of the housing units in San Francisco are covered by a rent control law dating back to the 1970s, which caps how much landlords can raise rents each year. The construction of new units coming onto the market is also a notoriously slow and expensive process. The city’s booming, tech-fueled economy has sent real estate price through the roof, but many landlords are unable to really cash in because they’re only allowed to set prices to market rate when new tenants move into a unit. While San Francisco doesn’t make evicting a tenant particularly easy, it is possible. Recent years have seen a wave of long-time residents kicked out of their homes to make way for a flood of deep-pocketed newcomers.

The boot camp, hosted by partner Daniel Bornstein, was meant as an education session for landlords to make the entire eviction process faster, cheaper, and more frequently successful—often by simply paying tenants a lump sum to leave willingly rather than fighting them on an eviction.

Unsurprisingly in a city known for its activism, the Bornstein’s sessions drew the ire of housing activists like West, who saw them as an embodiment of the rapid conversion of San Francisco into a gilded city exclusively for the rich.

After successfully fending off an eviction attempt himself a few years ago, West began working as a counselor at the San Francisco Tenants Union. ?Kind of like how Bornstein gives seminars to landlords on how to evict people; I do the same thing for the people on the other side who are being evicted,” he explained.

West had read the coverage about the boot camps and was intrigued. He had seen Bornstein & Bornstein letterhead on a number of eviction notices over the years and was curious to get a property-owner’s perspective on landlord-tenant battles. On Jan. 16, he attended a boot camp session inside an auditorium at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Center.

West had heard rumors that protestors might crash the event and, almost as soon as it started, those rumors were proved true. A handful of protesters rushed the stage, shouting slogans like, ?stop the evictions,” before they were quickly removed from the building. West took out his phone and shot a video of the protest, but stayed in his seat and watched the rest of Bornstein’s presentation.

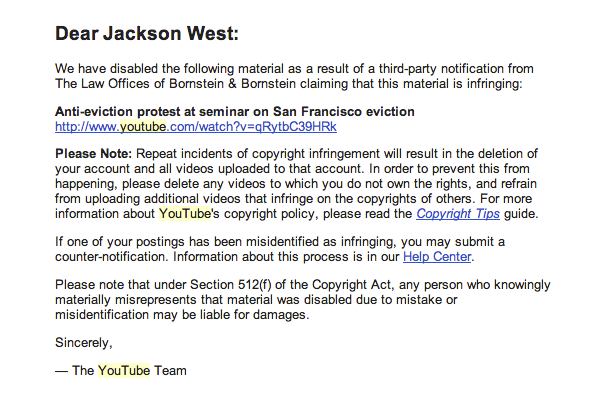

West took the roughly two-minute video, which only shows the protest without capturing any of the actual presentation, and posted it to YouTube. He wrote a unpaid blog post for Medium about the event, but didn’t give the video a second thought until he got a message from YouTube informing him that the clip was being taken down due to Bornstein’s claim that it infringed on his copyrighted intellectual property.

West was shocked. ?There was no stated prohibition on filming the event,” he said. ?There was no agreement I had to sign saying I wouldn’t take video.”

Under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), sites like YouTube aren’t liable for copyrighted content uploaded by users as long as they make a good faith effort to remove the illegal content when its presence is brought to their attention. With YouTube, when someone makes a DMCA copyright infringement claim, the site takes the video in question down for a 10-day period. During that time, the person who uploaded the video can file a counter-notice challenging the claim as illegitimate. If a counter-notice is filed, that video goes back up after 10 days, unless the supposed copyright holder files an actual lawsuit.

Aware of his rights in this process, West filed a counter-notice against Bornstein’s claim and uploaded the exact same video to Vimeo, competing video hosting site.

Anti-eviction protest at San Francisco landlord lawyer seminar from jacksonwest on Vimeo.

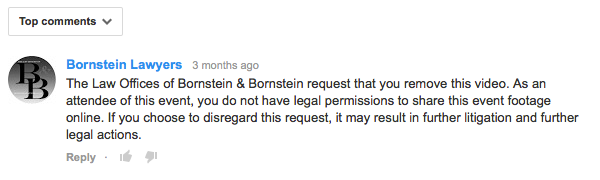

Bornstein actually attempted to notify West about his belief that the video was infringing on his copyright three months ago in a comment left on the video’s YouTube page.

For his part, West insists he never saw the comment until it was brought to his attention by the Daily Dot. “I make it a point to never read the comments on YouTube videos,” he said with a laugh. “Had I seen it at the time, I’m not sure what I would have done differently, other than probably just ignore it.”

According, to Daniel Nazer, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, if Bornstein attempted to sue to get the video taken down permanently, the suit would likely get laughed out of court. “This DMCA claim just doesn’t hold water. This video has a very clear documentary, journalistic purpose,” he said. “It’s really disappointing to see someone abuse the DMCA process like this, and it’s particularly disappointing to see it coming from an attorney.”

Nazer noted that speeches generally aren’t copyrightable material and, even if this one was in Bornstein’s case, the video doesn’t capture enough of the speech to exceed the boundary of fair use. “This isn’t the type of situation where there’s a legitimate copyright claim,” Nazer insisted. ?Maybe there the videographer was trespassing or something like that, but violating copyright is hard to justify here.”

West said that he contacted Bornstein before the SF Appeal story was published to get a comment. According to West, Bornstein implied that, if the West didn’t write his follow-up article about the takedown notice, the copyright claim against the video would be dropped and no lawsuit would be made to overturn West’s counter-notice on this video. ?I am not going to negotiate whether or not I will publish an account of this online in exchange for not getting sued,” West told the Daily Dot.

West decided to publish the story anyway.

Bornstein told the Daily Dot that he was not commenting to the media on the advice of his legal counsel. As of Tuesday morning, the video was reinstated on YouTube.

This sort of thing actually happens on a fairly regular basis. Google once noted that 37 percent of all DMCA claims it receives aren’t valid and 57 percent come from companies targeting competitors.

One of the highest profile cases of someone using a DMCA claim to knock down a video they didn’t like came in 2007, when conservative blogger Michelle Malkin posted a video critical of how rapper Akon dry humped an underage girl on stage during a concert. The video used a number of clips of Akon performing. The rapper’s label, Universal Music Group, objected—even though the company was apparently doing nothing about all the other videos of Akon performing that had been posted online without authorization. Arguing that the clips were clearly an example of fair use, Malkin fought UMG in court and ultimately prevailed.

In addition to directly challenging the takedown, there is some legal recourse for people who feel they have been targeted for DMCA takedowns unfairly. The law states:

Any person who knowingly materially misrepresents under this section…[material that] is infringing…shall be liable for any damages, including costs and attorneys’ fees, incurred by the alleged infringer, by any copyright owner or copyright owner’s authorized licensee, or by a service provider, who is injured by such misrepresentation.

?The problem is that a lot of people get intimidated, even around obviously bogus claims, and don’t file a counterclaim,” Nazer said. ?It’s very unfortunate that the DMCA allows for censorship as part of its process.”

H/T SF Appeal | Screengrab via Bornstein Law/YouTube | remix by Jason Reed