If you aren’t willing to abandon what made you a success as a triple-A game designer before making the leap to VR, your VR games might suck.

Oculus Connect 2, the second annual gathering of virtual reality designers hosted by Oculus, began Wednesday in Hollywood, California. The three-day event is divided by talks from game developers, virtual reality filmmakers, and companies like ILMxLAB—the branch of Lucasfilm working on virtual reality experiences—and a bevy of game demos on Oculus Rift and GearVR.

“Game Design Un-Rules: Examining Design Failures in ‘Time Machine’ VR” was one of the first talks scheduled at Oculus Connect 2. Patrick Harris, lead game designer at Minority Media, is a 10-year veteran of the triple-A video game industry. He started at Capcom Vancouver on the Dead Rising series and later went to Ubisoft, where he worked on the swordplay-based action game For Honor that premiered at E3 this year.

“I came into VR, just like I always do with everything, way too confident in my abilities and my past experience,” Harris said in an interview with the Daily Dot shortly before Oculus Connect 2. “And I screwed up. I made a whole bunch of terrible design decisions. Awful design decisions. And rather than be embarrassed and tuck them away and never speak of them again, I, for some reason, decided I would go to Oculus Connect and tell everyone about all the ways I’ve screwed up.”

Game developers, like craftsman in any form, tend to come up with rules—in this case rules for repeatedly developing the best game experiences possible for the largest audience. Codification of design principles is a particular necessity in the triple-A video game industry where budgets can bloat into hundreds of millions of dollars and the margin for error is slim.

These rules are sometimes expressed by very simple things, like where on the screen to place a pop-up menu so the player will immediately see it, but that it also does not obscure their vision. Or how to design aiming reticles—the crosshairs in the middle of the screen that tell a player what they are looking at or what they will hit when they pull the trigger on a gun.

“Aiming reticles are arguably one of the most refined visual elements in any video game,” Harris says. “There’s been a million shooter games. We know how to tell you where you’re shooting. And it’s simple and straightforward, at least now it is, because we know all this stuff.”

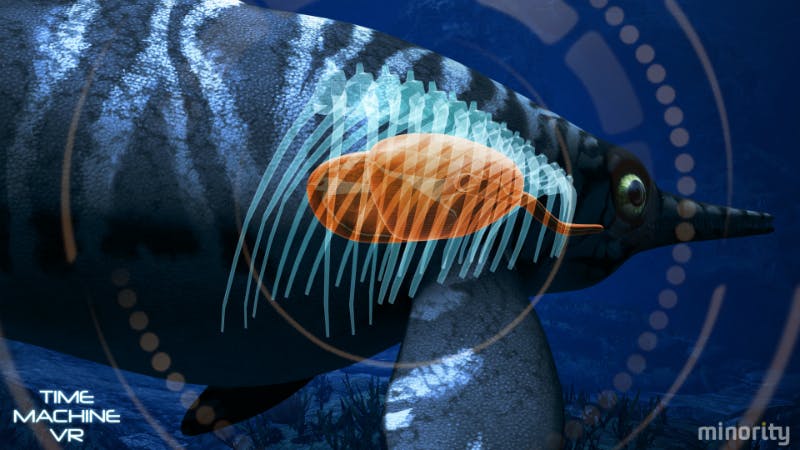

In Time Machine VR, a virulent plague is destroying humanity. You are sent back in time in a submersible vehicle to Earth’s primordial oceans to scan underwater dinosaurs and gain information about their biology and genetic makeup in the hopes of uncovering some clue as to the nature of the plague and how to defeat it.

To gain information about the dinosaurs, you point an aiming reticle at a dinosaur and launch a probe at it. In traditional gaming, designing this reticle might almost be an afterthought—a codified, simple task. Not so, in VR.

“I went, ‘We need to make a really cool aiming reticle,’” Harris said. “I thought, with VR, it can be three-dimensional, so like a holographic thing that you’re kind of looking down, like a series of circles that make it feel like this holographic sniper scope, and there’ll be like a little dot at the end that shows you where you’re going to shoot, and it’s going to be awesome.”

Now hold your arm up straight in front of you, give yourself a thumbs-up, and stare right at your thumb. This is like an aiming reticle in a traditional video game, which is being presented to you on a 2D visual plane. You naturally focus on your thumb.

Now look past your thumb, to the wall behind it. You will see two split images of your thumb, one from each eye. That’s what Harris’s aiming reticle in Time Machine VR did. In virtual reality, as in real life, the player tends to look outward, to seek the limits of their environment in order to orient themselves within the space, so Time Machine VR was rendering a reticle for each eye.

“Now what the hell are you shooting at?” Harris said. “There’s two red dots! Which one of them is the correct one?” The solution was to think about the reticle as something less precise, less like a dot at the end of a sniper scope and more like a large circle that usually serves in first-person shooters as a reticle for a shotgun.

“When you’re in VR, your brain is really good at spatial awareness, more so than you realize in most games,” Harris said. “And when you’re in an actual, immersive 3D world, that sort of holographic tube we were looking down ended up giving enough accuracy. You could judge where the middle of it was, without needing that really specific indicator,” referring to the red dot at the end of his holographic sniper scope concept.

Tried-and-true design wisdom failed. Adapting to VR solved the problem. And it’s the sort of problem that everyone at Oculus Connect 2 has to grapple with, because the Oculus Rift is scheduled to release in the first three months of 2016. Things are getting down to the wire, for the first generation of VR games and VR game designers.

Time Machine VR is currently in Early Access on Steam, meaning gamers can purchase an early, in-development build of the game and download updates as Minority Media applies them. The install base for Oculus Rift is composed right now of gamers who bought DK2, or Development Kit 2 Rift units, which will be inferior to the final, consumer models scheduled for wide distribution next year.

Harris isn’t concerned about Minority Media selling a million copies of Time Machine VR, because he understands the task ahead of all the VR pioneers in the gaming space.

“I look at it like the launch of any major console or piece of technology,” Harris said. “It has its own interesting challenges. I read a blog post a while ago that likened selling people on VR to selling people swimming pools on a planet where swimming pools aren’t a thing. It’s something that, when I tell somebody the idea, sometimes it’s tough to get them to understand. As soon as they put a headset on, they get it.”

“I read a blog post a while ago that likened selling people on VR to selling people swimming pools on a planet where swimming pools aren’t a thing.”

One fan was so impressed by a Time Machine VR demo at August’s PAX Prime gaming convention in Seattle, the fan emailed Minority Media to let them know he’d purchased a DK2 unit just so he could continue playing it.

“Whether out of the gate we sell a million billion copies, I don’t know?” Harris said. “The goal for Time Machine is to be the game that everyone plays when they have an Oculus Rift.” Minority Media has thrown its hat into the ring, in the contest to decide who will design virtual reality’s first killer app.

Winning, at this early stage in VR gaming is about being the studio that grabs the attention of the most influencers. The studio whose game comes up in conversation when the Oculus Rift consumer models finally hit the marketplace, and new owners ask veteran VR gamers (those who own DK2 units) what games they ought to be playing first.

The opening for that kind of massive, influential game is wider than it’s ever been, in terms of the size of the studio that might take the prize. Smaller studios, like Minority Media, and even small teams of indie developers can afford to be more nimble than giant development studios pumping out annual triple-A blockbusters.

It’s easier for smaller studios to unlearn what they’ve learned, in the face of a changing industry whose boundaries encompass the world of VR gaming.

“I think it’s open to studios that people don’t expect,” Harris said. “I’m hoping that it’s Time Machine, but if something else beats us and is the killer app, I think it’s going to come from a studio that we’ve never heard the name of before.”

Illustration via Minority Media