On a Thursday evening in mid-January, around 6pm or so, I showed my wife a game called Cookie Clicker. She scoffed. ‟So all you do in this game is click on a picture of a cookie over and over again?”

‟Basically,” I shrugged. ‟I’m not sure I really understand it myself.”

Around 2am that night, I had to physically drag her away from her computer. ‟Just a few more cookies!” she protested. “I’m almost at a billion!”

Outside of the occasional nostalgia-fueled trip around a Mario Kart track, my wife isn’t much of a gamer. So when something hooks her so thoroughly that I become legitimately worried she’s going to break her mouse with her non-stop clicking, it’s got to be tapping into something elemental.

Simple, addicting games that appeal to casual gamers are nothing new. Just look at the countless hours people around the globe have sunk into playing Flappy Bird or Candy Crush Saga—the massively popular mobile game where players line up matching pieces of candy in increasingly difficult to solve puzzles. The game often seems more like an elaborate collection of psychological ploys aimed at tricking users into spending cash on in-app purchases, however.

But the premise behind Cookie Clicker is far more straightforward: See that picture of a cookie? Click on it. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

There are other elements to the game too, namely an ability to use the cookies you’ve created to purchase items like cookie-baking grandmas and cookie dough mines that automatically produce more cookies for you. But the core of the gameplay is the simple, mind-numbing act of clicking a single button ad nauseam.

Only a few months after it was first launched, the free, Web-based browser game—initially created as a joke by a lone French developer in a single evening—has racked up over 86 million hits and spawned scores of imitators. These ‟incremental games” have their own thriving community on social news site Reddit. There, budding developers show off their latest creations and debate the finer points of a budding new genre that’s already warranted its own BuzzFeed listicle entitled ‟The 18 Stages Of A Full-Blown ‛Cookie Clicker’ Addiction.”

To get a sense of how the game is played, check out at least a little bit of this speedrun where a fleet-fingered player makes it to 1 million cookies in just over 17 minutes:

Cookie Clicker was created last fall by 24-year-old French game designer Julien Thiennot, who goes by the nickname Orteli. Thiennot has been making games since childhood, though ‟game designer” in the traditional sense may not be quite the best way to describe what he does. Like the post-modern playwright who can’t help but break the fourth wall every chance she gets, Thiennot’s games are all about pointing gigantic flashing arrows at gaming conventions most people take for granted. As much as the things Thiennot creates can be considered games, they’re also ingeniously twisted works of wry conceptual art.

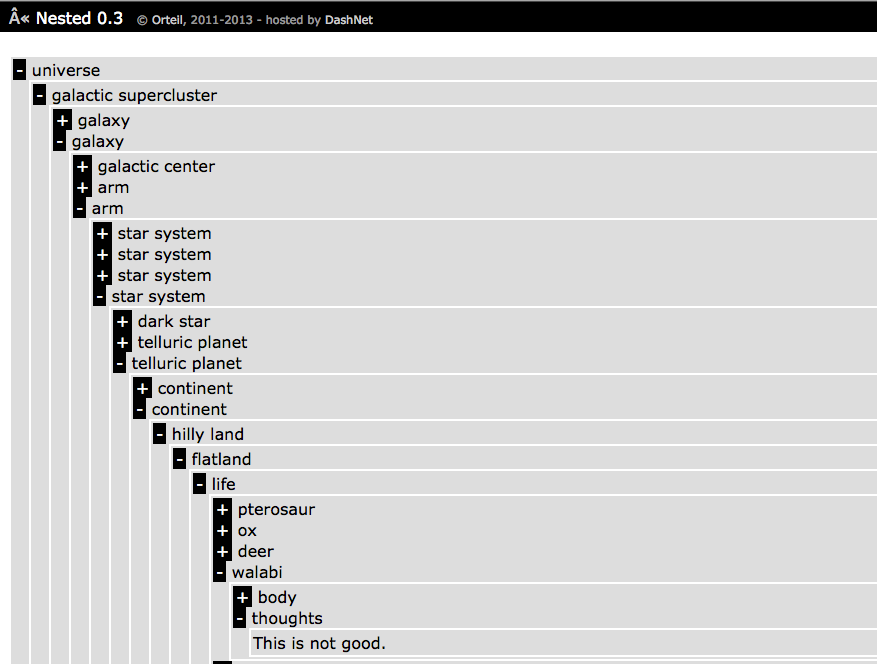

A good example is one of his games called Nested. The premise is viewing the entire universe as if it were organized like a computer’s file structure:

Rather than games, Thiennot prefers the label “experiments.”

The initial idea for Cookie Clicker, Thiennot explained, came while playing an online text-based game called Candy Box. The game works by letting players collect pieces of candy, a process that happens automatically at a set rate as you stare at the screen. It begins by allowing you to only eat candy or throw it on the ground but soon evolves into an epic ASCII art RPG packed with monsters to be slayed and lollipops to be farmed.

Thiennot became fascinated with the ‟very dull (but strangely entertaining) mechanic” of an entire game being based on a slowly ticking counter, but he quickly realized the satirical possibilities of replacing the mechanical counter with something hand-operated. So Thiennot stayed up late one night throwing together game that used this conceit to essentially mock the entire idea of grinding through a video game.

A few days later he posted a link to the game on the influential, albeit anarchically profane, online message board 4chan’s video gaming forum, /v/. For an indie developer like Thiennot, posting a creation to 4chan is like throwing it into the deep end of a pool filled with vicious sharks—4chan users aren’t afraid to let him know how much he sucks.

But the denizens of /v/ immediately took to the game. ‟H-how am I enjoying this…how?” asked one anonymous poster. (And true to form, 4chan users also suggested allowing players be able to sell their in-game grandmas.)

“So I take it the experiment is a success,” replied Thiennot. He was shocked when the game registered over 50,000 plays in just the first few hours.

People even started making Cookie Clicker tribute videos:

‟I was hella surprised,” he wrote in an email. “People were actually playing my joke game unironically! It seemed like the madness kept growing crazier—people were posting their progress, data-mining for secret features, making spreadsheets dedicated to optimizing cookie production, creating mods for the game.

“At first I couldn’t tell if people were just going along with the joke or actually being serious.”

As with any popular game nowadays, Cookie Clicker triggered a wave of imitators. Some just stole the game’s mechanics wholesale and replaced cookies with sushi or candy. Others stole the whole concept outright, banking on players confusing their rip-off with the original.

“I’d say those are pretty vile and lazy,” Thiennot complained. ‟I mean, can’t they at least come up with something else than cookies?”

Others, however, have taken the concept in really interesting directions. Some notable examples are Clicking Bad, where players get to fill the shoes of a Walter White-esque meth kingpin, and CivClicker, an empire-building game that splits the difference between Cookie Clicker and Sid Meier’s Civilization.

One of my personal favorites is simply called Journalism. It involves clicking on a big red button labeled ‟Write!” to bank words players can spend on tweets, blog entries, or even full-length books. The only way to win the game is to get a power up labeled ‟quit journalism.”

What makes incremental games so addictive is that they manage to strip away almost everything superfluous about gaming. What’s left is a chocolate-chipped version of famed psychologist B.F. Skinner’s experiment, known as the ‟Skinner Box,” in which animals were trained to push a button to receive a food after a set number of clicks. As the number of button pushes required for food gradually increased, the animals would keep smashing it ad infinitum.

And yet, when it comes to incremental games, it’s not quite that simple. The games only start out with frantic clicking. After a while, players can use their haul of clicks to automate the process. In Cookie Clicker, hiring a legion of grandmas allows players to sit back, rest their fingers, and watch batch after batch of fresh cookies roll in. Maybe it’s because a player is forced to physically click thousands of times in order obtain those grandmas, but there’s something very psychologically satisfying about seeing the process automate itself. It’s analogous to Cookie Clicker’s real world corollary: a small business owner who spent years baking cookies by hand and is finally able to afford to pay someone else to do the grunt work. A Marxist reading would frame it as someone’s class transition from labor to capital.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, the director of the psychology division of the International Gaming Research Unit at Nottingham Trent University, explained that the very action of repeated clicking is a crucial aspect of what makes them so addictive: It allows players to get wrapped up in the whole physicality of playing the game. The slow reward structure is also key.

‟There are incremental rewards that are the basis for all human behaviour,” Griffiths, who is also a member of the British Psychological Society’s cyberpsychology department, said.

“People don’t repeat behaviour voluntarily unless they perceive it as rewarding–psychologically, physiologically, socially and/or financially–and the rewards do come with persistence in these types of games.”

Now that Thiennot has figured out the formula to create a successful incremental game, he’s making a concerted effort to assist in their spread. Late last month, he unveiled a program allowing people to make their own Cookie Clicker knockoff, no programming knowledge required.

One particularly promising idea for a game was pitched in a post on Reddit. A user called Falzar proposed a game called U.S. Debt where, ‟the clicker button [would] be ‛Borrow $1.’ And [it would] gradually build up to collateralize debt obligations and whatnot. A prestige reset might be ‘declare bankruptcy’ (which returns your debt to zero).”

One major potential downside to click-heavy games remains, however: broken mice. Though one devoted fan insists my fear is overblown.

‟For me it hasn’t been an issue,” wrote Reddit user u/dissk, who serves as a moderator of the r/incremental_games community. “But my clicking finger has begun to hurt for a while.”

Illustration by Jason Reed