The internet may seem like a black hole sometimes, but soon enough we’ll be able to see the real, interstellar kind. Sort of.

We can’t actually see black holes, since they consume light particles, but we can photograph light particles going into a point called the “event horizon.” Now, six telescopes around the world are collaborating to do just that.

These six telescopes will work together as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) to cohesively photograph the event horizon of Sagittarius A* (pronounced Sagittarius A Star), a black hole right in the middle of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. Additionally, EHT will be targeting another black hole in our neighboring galaxy, M87.

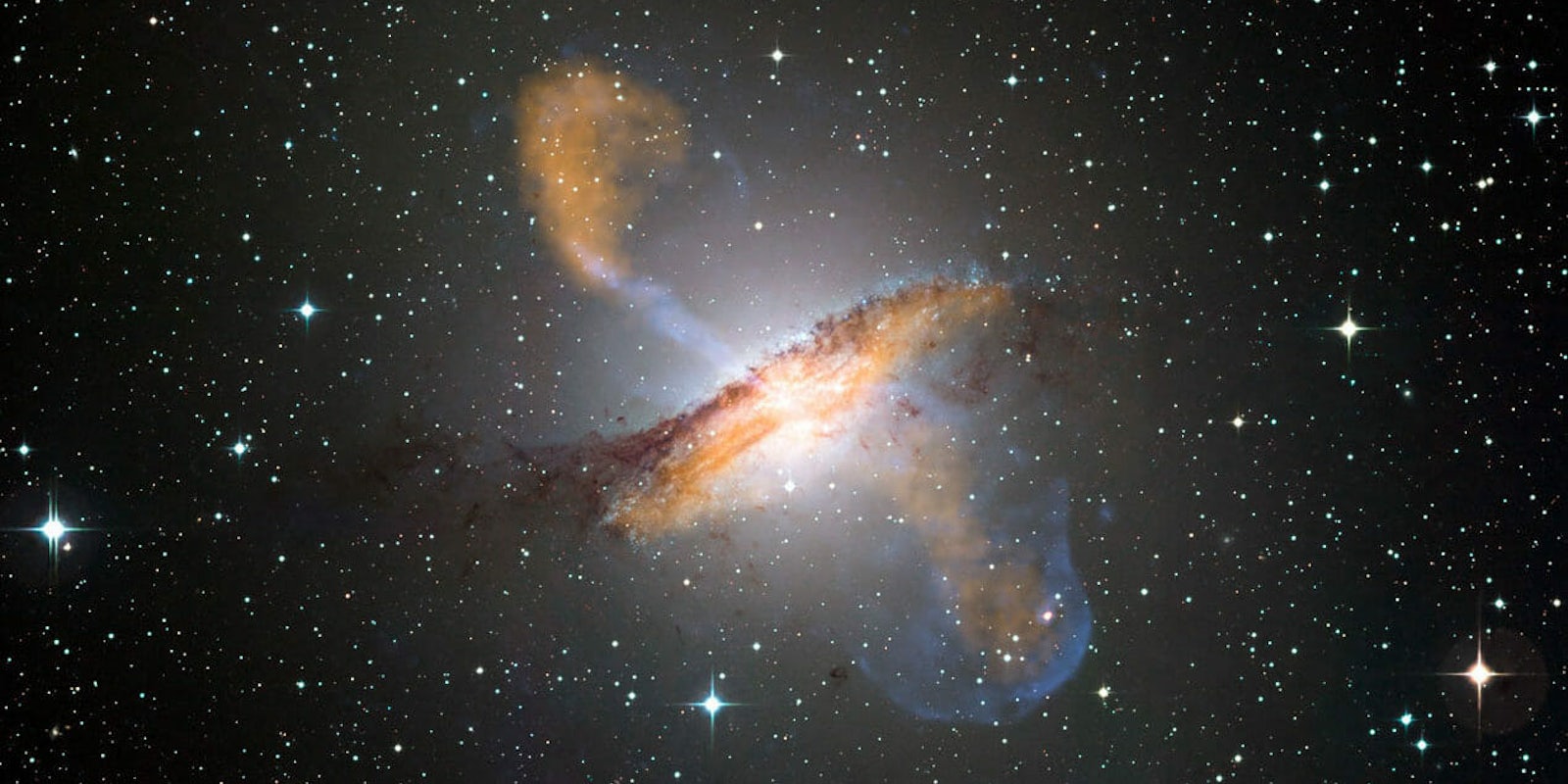

Vincent Fish, research scientist for the MIT Haystack Observatory, says hot plasma—like a literal billion degrees kind of hot—around the black holes glows enough to be photographed.

“You can’t see the event horizon of the black hole itself,” Fish told the Daily Dot. “But, the black holes we’re looking at aren’t surrounded by nothingness…It’s very hot plasma we’re seeing.”

A method called VLBI (Very Long Baseline Interferometry) is used to link the six telescopes so they can capture images as a gigantic single telescope.

“The idea behind VLBI is that you use two or more telescopes and use interferometry between them,” Fish says. “You get data that has the resolution as though you had a telescope as big as the distance between them—not the sensitivity—but you can resolve the finest details of the sky as if you had a telescope that big.”

Though the images are being taken this month, they will not be released to the public until 2018. Some of this has to do with the process of putting all the images together. However, most of it is just because since space is huge, digital photos of space are huge.

“At each telescope we record a lot of data,” Fish says. “We’re recording 32 gigabits per second at each telescope, so that’s 4 gigabytes per second.”

For perspective, a full-length high-definition film is roughly 4 gigabytes. Imagine downloading all of your favorite movies in a single second. It will take scientists months, if not years, for all the data to be sifted through.

Fish says the files will be physically transported back to MIT for processing because the internet cannot handle the speed of data. Yep, you read that right.

“Some of our telescopes are in remote locations,” Fish says. “We’re using the South Pole telescope, and the internet is terrible there.”

We can only imagine.