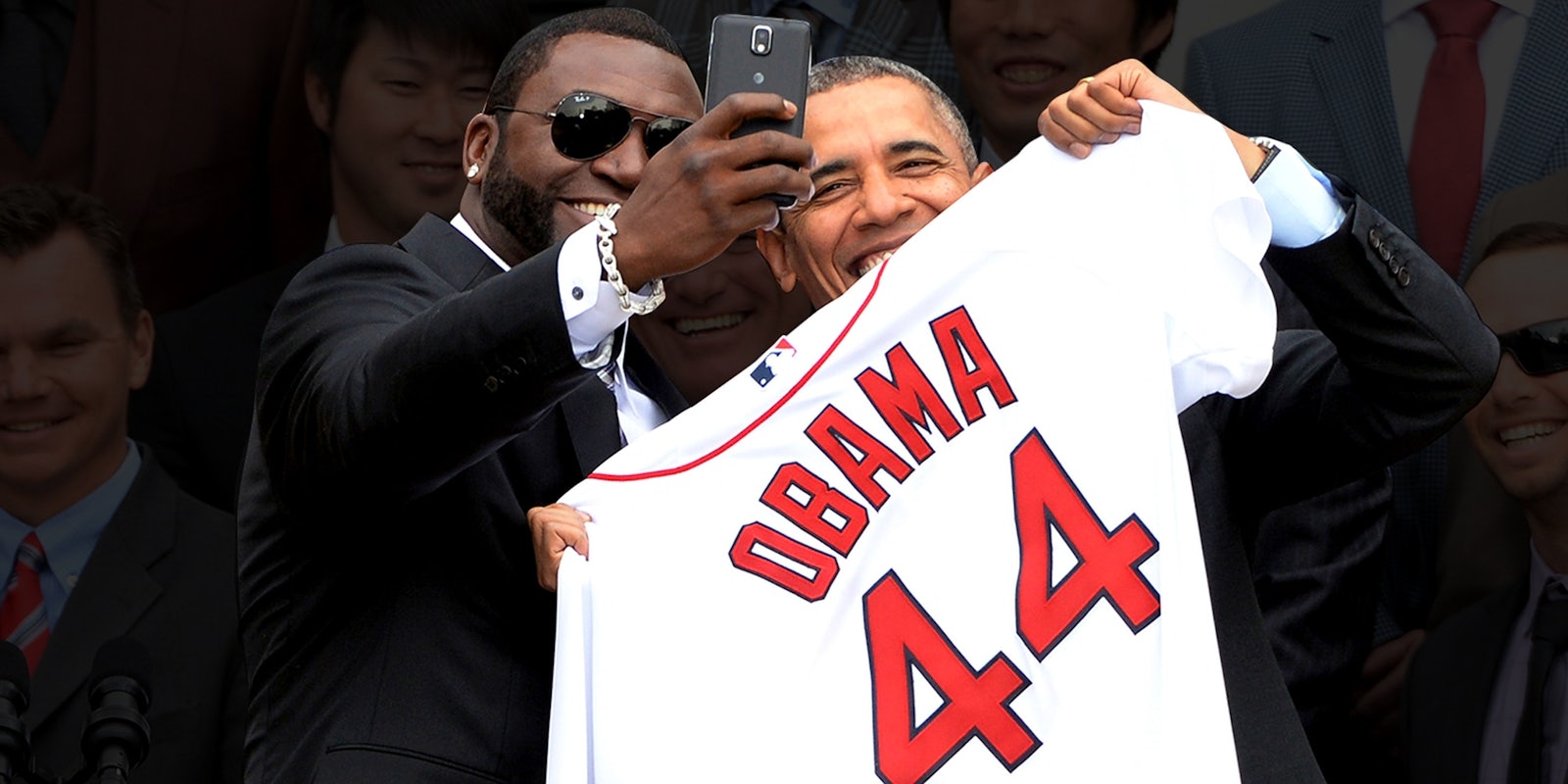

When Boston Red Sox hitter David Ortiz whipped out his smartphone as his team received congratulations for winning the 2013 World Series at the White House, he took what appeared to be a spontaneous and joyful selfie with the President of the United States. Ortiz posted the photo, which shows Obama grinning with other Red Sox in the background, to Twitter. Like the selfie Ellen DeGeneres posted from the Oscars, it was widely circulated; people liked the seeing a baseball star and the most powerful man in America casually smiling together, sharing a fun moment.

What an honor! Thanks for the #selfie, @BarackObama pic.twitter.com/y5Ww74sEID

— David Ortiz (@davidortiz) April 1, 2014

Except. For Ortiz, it wasn’t about fun. It was about money. Samsung had paid him to take the photo as part of an advertising campaign, unbeknownst to the president. Samsung, as you’ll remember, also sponsored the Oscars, where DeGeneres gave Bradley Cooper a Galaxy phone and told him to say cheese. Apparently the Korean tech corporation’s new advertising strategy hinges on tricking celebrities into taking promotional selfies. Samsung has co-opted the selfie for marketing purposes, specifically the celebrity selfie.

In many ways, this is appropriate. Selfies are about self-promotion, after all, so why shouldn’t they also be about commercial promotion? It’s not like selfies are a revered form of self-expression; in fact, they’re a form of life-documentation derided as singularly banal. Selfies aren’t exactly chic. They’re gauche, they’re gaudy, they’re shameless, and they’re so normcore they make Old Navy look like a pop-up anarchist boutique in Budapest. And selfies featuring middle-aged mainstream celebrities are especially uncool.

The White House is not happy that the president was tricked into appearing for commercial purposes. But besides Jay Carney, who cares if Samsung used the Oriz-Obama selfie as a marketing tool?

This is far from a new trend. Remember when people freaked out because the high-end Met Ball was punk-themed in 2013? Or every time a supposedly hip celebrity has been accused of selling out for endorsing a commercial product? Bob Dylan, once considered a folk hero, has shilled for Victoria’s Secret. The line between “pure” culture and commercial culture has been crisscrossed so many times it looks like a railroad junction.

Advertisers, promoters, and marketers have been glomming onto youth culture for decades (and culture-makers looking for a payday have been welcoming that glomming.) Political analyst and journalist Thomas Frank wrote a book published in 1997 called The Conquest of Cool that outlines how often this kind of thing goes down, and why.

“Rebel youth culture remains the cultural mode of the corporate moment, used to promote not only specific products but the general idea of life in the cyber-revolution,” Frank writes, then lists example upon example: Nike using counterculture icon William S. Burroughs to sell shoes, tech companies like Apple touting their products as tools of the revolution, Coca-Cola using imagery of Ken Kesey’s hippie-freak acid-trip bus to sell pop. This Samsung selfie schtick is just another entry in a very thick book about ways corporations have adopted youth culture.

That’s not to say that Samsung’s campaign isn’t gross. It is. And it underlines that marketing teams are getting even better at identifying ways to inject commercial advertising into unexpected places.

Even though selfies aren’t considered a rebellious or countercultural symbol, and much better and more beloved signs of youth culture have been co-opted too many times to count in the past, there is a reason to lament Samsung’s weird, sneaky selfie-promotional campaign. In the examples outlines in Frank’s book and in traditional marketing and advertising, it was never difficult to co-opt youth culture, but it was difficult to do it without the promotional aspect becoming obvious.

When Bob Dylan sang in a Victoria’s Secret commercial, no one thought it was performance art. He didn’t disguise his activity by carefully slipping praise for silk panties into an update of “Lay Lady Lay”; his paycheck was not in question.

The Samsung selfie campaign is different. They aren’t obviously commercial; they appear genuine. They are much closer simulacra to the organic, and they turn famous people into unwitting (or, sometimes knowing) shills. As Frank points out in his book, corporations chase after youth trends in order to “dramatize their insurgent vision,” and with its weird faux-underground selfie campaign, Samsung is taking that “insurgent vision” idea a step further by hoodwinking participants and the audience. In this way, Samsung is co-opting both selfie culture and online hoax culture (which makes it doubly infuriating.)

At this point, people are inundated with ads. We understand that we are going to see them. Advertisements, even those that shamelessly gobble youth trends, aren’t offensive. What is offensive is being tricked into consuming culture without realizing its selling something. Perhaps we are supposed to think Samsung is being clever by punking people into being in guerilla ads.

Instead, it seems like a strangely circumspect and unnecessarily conniving way to get people to think about the products—there’s nothing aesthetically noteworthy about these selfies taken by Samsung phone cameras, so it’s not like people are looking at them and thinking “Wow, what a beautiful shot, I wonder what kind of camera took that?” They just think it’s cute that these celebrities took a selfie together, and then feel confused/annoyed when it turns out one of the celebrities was covertly forcing the other one to be part of an ad campaign.

In February, a Vice writer argued that NekNomination, the messed-up online drinking game, was the sad equivalent of what passes for a genuine subculture in 2014 because NekNomination is one of the only things too stupid and toxic to be co-opted. “Youth subcultures are processed in the same way as veal. They’re snapped up by trend forecasters before they’ve had a chance to grow, locked in a dark room, sold to the high-street butcher and flogged back to the kids at inflated prices,” the article states. “Very few brands are going to encourage you to drink engine oil any time soon—they don’t want a shout out at your funeral, they want your money. NekNominate doesn’t, and it remains nihilistically enticing for that.”

The Samsung selfie campaign shows that selfies and other digital trends aren’t outre enough to avoid co-option. And it’s worth discussing not because of anything to do with selfies or the celebrities that Samsung tricked (although the audacity of hoodwinking the president is notable). What makes the campaign troublesome is the way it further erodes the distinction between a cultural moment and a commercial one, and how it showcases how quickly something can go from a cultural flashpoint to a way to sell fancy phones.

Photo via the Washington Post