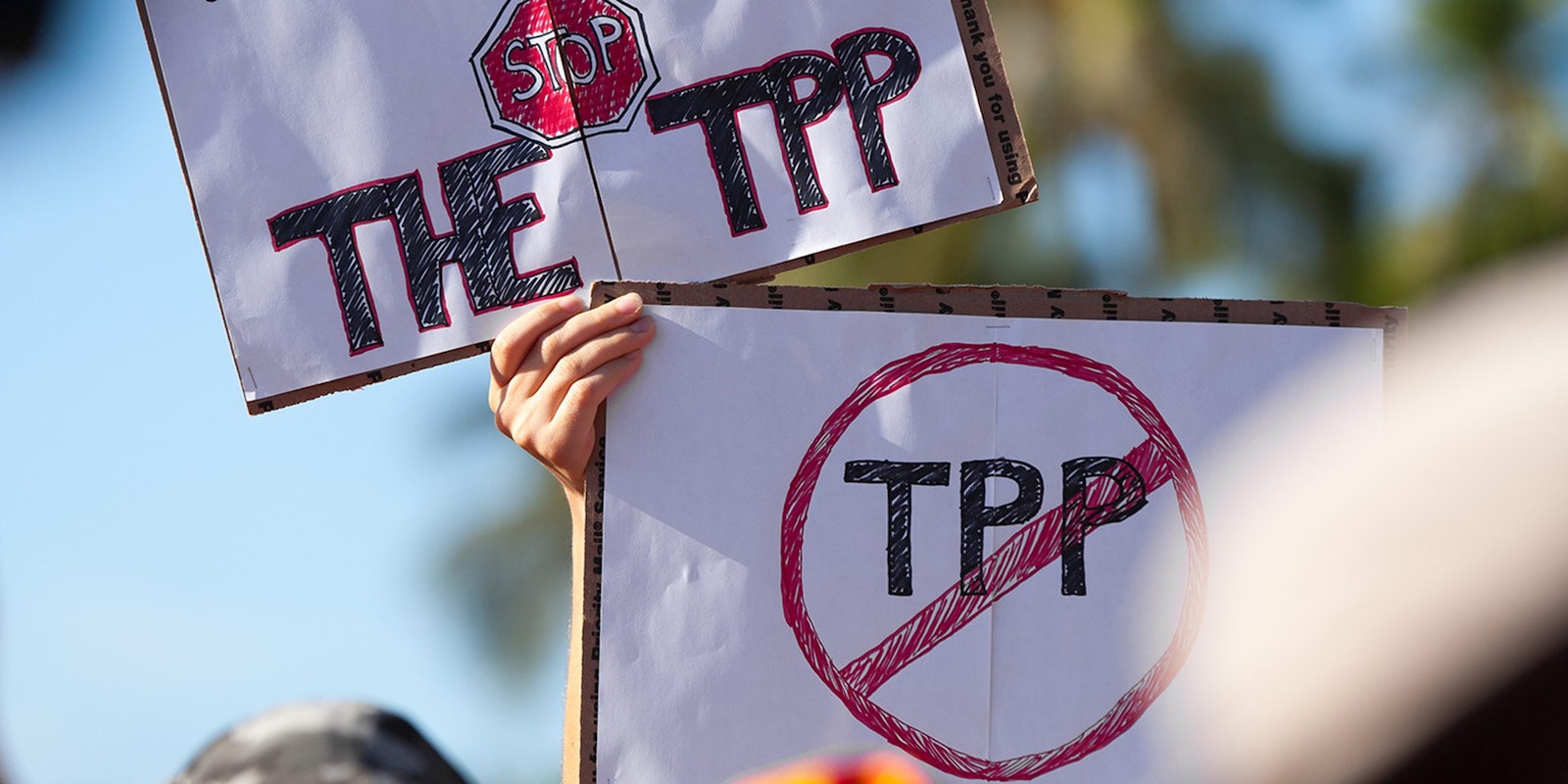

On his third day in office, Donald Trump signed an executive order to withdraw the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

After seven years of negotiations between 12 countries, the Obama administration’s signature trade bill appears to be D.O.A. Despite being a frequent talking point on the 2016 campaign trail, questions still linger about the TPP: What it is, why it’s controversial, and what happens next.

Here’s what you need to know.

Start from scratch. What is the TPP?

It’s a proposed trade deal—like NAFTA, for example, but for countries scattered around the Pacific Ocean. Member nations include the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Oceana, and a handful of countries in South America and Asia. On Monday morning, trade representatives from those countries announced they’d agreed on a text they think their countries will all sign off on.

As for what’s in the TPP? Its range is pretty broad and it covers more than a dozen topics, including the environment, labor, textiles, medicine, and—this part is huge for the internet—intellectual property. You can read the full text of the TPP here.

Proponents say this will secure jobs, fight corruption, and secure better trade and labor practices around the world. Opponents say it’s purely an enormous, international corporate power grab and won’t actually help anyone else—and will likely cause untold harm.

Then what’s fast track?

“Fast track” is a nickname for a temporary power that Congress gives to the president. Formally, it’s called “trade promotion authority,” and it’s based on the fact that Congress has to approve a trade deal before the U.S. can adopt it. It seems odd that anyone in Congress would ever want to voluntarily give up power, but fast track bundles up trade agreements as an all-or-nothing deal to keep members of Congress from bickering about it for eternity.

Counterintuitive as it may be, fast track makes sense if the government is serious about adopting the TPP. Considering the trade representatives of the TPP nations didn’t agree on a final text after four years of negotiating, it seems impossible that Congress would pass it if it were allowed to squabble over individual portions.

Congress passed a fast track bill in June, meaning that there’s no hope of trying to get your elected representatives to change what’s in the text. All they can do is vote yes or no.

Who decided what’s in the TPP?

Not you, not me, and not your elected officials. Just the trade representatives from those 12 nations and those people are pretty influenced by the big corporations that actually engage in this kind of trade. More on that in a bit.

Each of those dozen countries were involved in negotiations, though that number has grown slowly since they started in 2010, and it seems there’s always been some country or another on the precipice of leaving. New countries—China is a very notable example—can join the TPP, but the text is set.

Most of the members are either North American—the U.S., Canada, and Mexico—or Asian—Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Chile is there, too, as are Australia and New Zealand.

But it’s not these countries’ entire governments who argued about the TPP’s content; it’s their trade representatives. Current U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman, who took over from Ron Kirk in 2013, has been particularly opaque about what the U.S. is doing.

What did they negotiate about?

If you weren’t yet impressed with the TPP’s scale, then check out its scope. The TPP’s drafts are broken down into 14 chapters, a number first revealed in a Nov. 13, 2013 section leaked to the public by WikiLeaks. Imagine trying to get a dozen nations to agree on trade regulations in as disparate areas as e-commerce, labor, and the environment, and you’ll have a sense of why talks have repeatedly stalled.

What’s actually in the TPP? Why did everyone act like it’s so sketchy?

Those two questions are pretty intertwined. It seemed sketchy because almost no one had been given access to the draft text or details about the negotiations until its release in November 2014. Only a handful of people, like the staffs of member countries’ trade representative offices, could attend the negotiations. Members of Congress, for instance, had been given temporary access to drafts, and their aides were long forbidden to view the text of the deal.

This isn’t unique to the TPP; it’s standard practice for a major multilateral trade deal. But what’s disturbing to many people isn’t that access was restricted, it’s that corporate lobbyists do get to attend negotiating rounds to speak with participating countries. Initially, journalists and nonprofit and public advocacy groups were also allowed to lobby TPP negotiators. But they were later blocked out.

Why did people assume it’s bad?

Because someone, or maybe multiple people, leaked TPP updates to WikiLeaks. Several working chapters—the ones on the environment and investment, as well as two updates on the intellectual property chapter—were published on the site in their entirety. And yes, they were all heavily criticized.

A common refrain from TPP critics is that it’s “undemocratic.” Traditionally, this is how trade deals work. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

Who supports the TPP? Who opposes it?

Corporate lobbyists get essentially exclusive access to influence its negotiators, and it’s a huge trade deal, so as a rule, TPP supporters are friends of big corporate trade. Pretty much all the major corporations you can think of—Apple, Citigroup, Exxon, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Monsanto, Walmart, etc.—are open supporters.

Conversely, a broad coalition of public advocacy groups oppose it. The Sierra Club warns it could “lead to increased stress on natural resources and species including trees, fish, and wildlife.” Consumer advocacy nonprofit Public Citizen says that the investment chapter would allow corporations to sue governments they find in breach of TPP provisions. Major labor unions, like AFL-CIO and CWA, also oppose the agreement because it appears to give significant powers to corporations at the expense of workers. And then there’s the “bad for the Internet” thing, which I’ll dig into in a second.

What about in D.C.? Who’s for it and who’s against it, politically?

This is one of the rare issues that pits President Obama and Republicans in Congress on one side and congressional Democrats on the other. And most are pretty entrenched. Obama was very, very set on the TPP happening while in office. It was part of the reason he nominated Froman in 2013, and he even talked about the TPP during his 2015 State of the Union. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Senate finance committee chair Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) are big fans.

House Democrats, on the other hand, have long pledged in bulk to oppose it. And while former TPP critic Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) is a supporter, some of the biggest rabble-rousers in the Senate, like Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), have vowed to fight it.

How does TPP fit into the 2016 election?

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential nominee, came out against the deal in 2015—but that was after she strongly supported it. This about-face became a major point of contention for Clinton’s primary challenger, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who has long opposed the TPP.

Interestingly, the TPP is perhaps the one area Clinton, Sanders, and Republican nominee Donald Trump agree. Trump has come out strongly against the TPP, in opposition to many in the Republican Party.

Gary Johnson, the Libertarian presidential candidate, recently told CNN that he supports adoption of the TPP.

So what’s this about it being terrible for the internet?

The devil, it’s safe to say, often resides in intellectual property law. The Internet freedom concern is rooted in the intellectual property chapters. And the problems boil down to a few potential consequences: harsh punishments for copyright infringement, such as kicking accused online pirates off the Internet entirely, and outright censorship of websites.

The office of former U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk has previously told me that they would never agree to an IP chapter that contradicts current U.S. law. Froman’s office has never responded to my numerous requests for comment.

But even if Kirk’s office is right, that’s not that high of a standard. Under the U.S.’s big Internet copyright law, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), it actually is legal for an Internet provider to cut off the service of a suspected serial copyright infringer. Couple this with the fact that it’s very easy to be mistakenly accused of Internet piracy or to use copyright law as a censorship tool. Couple that with the aforementioned fear that the TPP allows corporations to file lawsuits over fears of copyright infringement, and you see why this is raising alarm bells.

Besides, as online-rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has noted, our copyright law’s saving grace is that we have provisions for fair use, which means you can use copyrighted material when it’s transformed enough to become entirely new intellectual property, like satire or commentary. Fair use plays a much bigger role in your online experience than you realize—it lets you see a thumbnail of a picture when you do a Google image search, for example.

To be fair, Sen. Wyden, amidst a recent flurry of pro-internet legislation, said in an April 2015 op-ed that he “successfully pushed U.S. trade negotiators” to make that chapter more consistent with fair use. Advocates who normally support him are very skeptical.

Additional reporting by Andrew Couts and Austin Powell.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated for relevance.

Photo via SumOfUs/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)