The reality of America’s privacy dilemma is setting in as people realize, finally, that they do have something to hide after all.

South by Southwest festival-goers were shocked by Edward Snowden’s classified disclosures in 2014. A year later, corporate executives appeared at various conferences, warning about the devastating effects of “dragnet,” mass-collection surveillance on American-owned enterprise.

You do not require “something to hide” in order to “hide something.”

Now SXSW panels stress that privacy is no longer a given. That it requires forethought, initiative, and to a certain degree, technical expertise. Most people don’t own the information that defines them. Their consumer history, travel records, and even their personal relationships are bought, sold, and traded for profit or worse.

Major legal battles, such as the ongoing FBI versus Apple case, perpetuate the idea that the future of privacy hinges on a single or series of court decisions. But in truth, these ever-important legal battles represent merely a small fraction of privacy rights imperiled. This was the lesson two IBM employees—security architect Ron Williams and UX designer Hyun Seo—brought with them to SXSW this week.

On the fourth floor of the J.W. Marriott in downtown Austin, Texas, Williams and Seo set out to define what privacy means in 2016. This is the latest in the conference’s privacy panels.

“What control can you have over your personal privacy?” Williams asks rhetorically. “What do you have no control over? What do you yield control over in your personal interactions.”

Privacy, as he broadly defines it, is “being free from unwanted or undue intrusion, or disturbance in one’s life or affairs.”

He continues: “That means a lot of things in different context.”

A photograph of a glass room in the forest with a toilet inside it appears on the projection screen.

“If the information is not in your head,” Seo interjects, “You should probably consider that public information.”

While government surveillance is the mostly widely discussed form of privacy invasion, the personal threat is low, according to Williams.

“As the government increases its ability to collect data, it is bounded by law in terms of what it can do with it,” he says. “So I’m not particularly worried at this point in time, and I’m not in the near future worried about the government suddenly, or someone in the government, deciding to target me because I work for a particular company, I live in a particular area, or I express particular views on social media.”

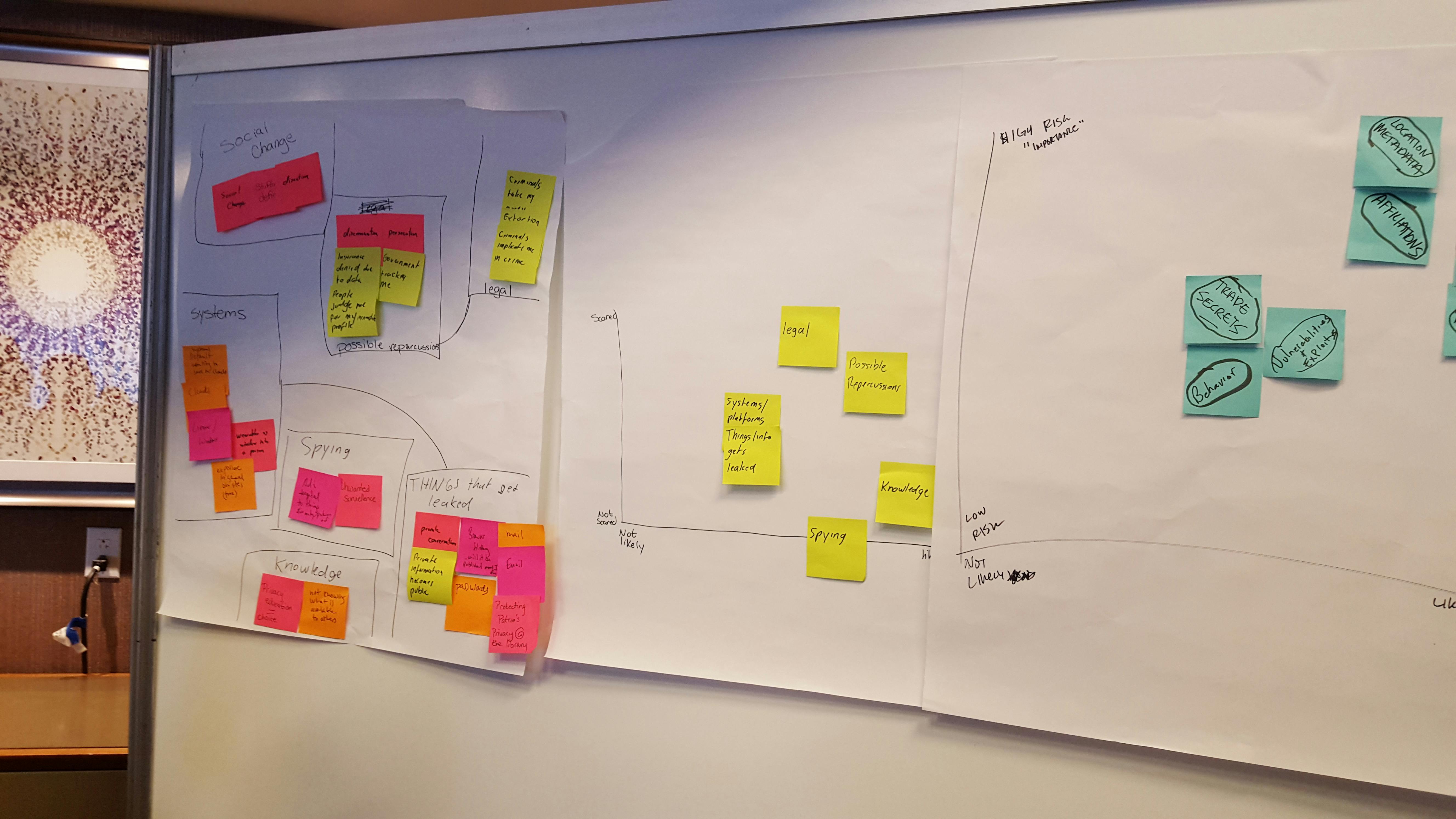

The speakers direct the group of roughly 40 technologists, filmmakers, and journalists, to jot down in under 60 seconds as many privacy concerns as possible on a pile of sticky notes. Working against a clock, the perennially cited “nothing to hide” argument is quickly dispelled.

Whether they’ll admit it or not, I’m told, no one wants their browsing history shared with the public. No one wants their every movement tracked by corporations with the nearly unlimited ability to trade and sell that information to whomever they want. (When I shrug at the prospect of my GPS metadata being leaked online, a woman nearby turns and asks, “Have you ever been in a divorce?”)

It’s almost certainly true that no one wants even their text messages, photos, or home movies—what Williams calls “the stuff mom grabs when the house is on fire”—falling to the hands of strangers, or being hacked into and deleted forever.

As preeminent psychoanalyst Emilio Mordini would say, you do not require “something to hide” in order to “hide something.”

When 60 seconds are up, the speakers instruct the participants to sort their sticky notes into a handful of broader categories. Photographs, emails, and text messages become “content”; financial details, medical records, and legal correspondence are grouped into “personal accounts”; family ties, friends, and other associations become your “affiliations.” Each category represents a different aspect of the participants’ private lives and each carries varying degrees of risk.

The U.S. government’s dragnet surveillance programs are the most frequently discussed privacy threat by far, but noticeably most of the participants failed to acknowledge it in the allotted time. While it is highly likely government spies are collecting every morsel of information they can get their hands on, there were few people in the room concerned about the immediate effect it would have on their lives.

The participants begin attaching their sticky notes along a graph drawn crudely on a poster board. The higher the notes go, the more frightened they are about the possibility of the information getting stolen or leaked; the farther to the right they place the notes, the more likely they believe it is the information will be breached or intercepted by unwanted parties.

“I’m not in the near future worried about the government suddenly, or someone in the government, deciding to target me…”

As an example: I’m a journalist, and therefore highly concerned about the exposure of confidential sources. But that fear compels me to take extra precautions so I don’t think it’s very likely to happen.

Government surveillance, again, falls under “highly likely” for most of the participants, but they don’t seem too concerned about the possible repercussions. Former lovers and employers generally weigh more heavily during the privacy-threat assessment. “Blackmail” and “stalkers” appear on most of them.

As the event comes to a close, Williams leans forward and whispers something into a young girl’s ear. Everyone witnesses the birth of the secret and acquires a bit of metadata about it: We all know who has the secret, and when and where it was shared, but none of us are sure what the content of the secret is—or so we think.

A man in a black button-down shirt raises his hand. “Actually, I heard you,” he says. The whispering protocol was flawed. I remember what Seo said two hours earlier: If it exists anywhere but inside your head, there’s no reason to believe it is private.

Photo via Luxbao/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman