With the 2016 elections looming large in the distance, congressional Republicans have taken up arms against Planned Parenthood and its annual $500 million in federal funding, with some going as far as to threaten to shutdown the federal government to take the money away.

Following the release this year of several “sting” videos targeting Planned Parenthood, abortion has become one of the leading issues among GOP presidential candidates. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee accused the organization of profiting the sale of fetal organs, saying it “rips up [body] parts and sells them like they’re parts to a Buick,” with others on the Republican ticket echoing this gruesome accusation.

Planned Parenthood has denied accusations of wrongdoing spurred by the videos, recorded undercover by an anti-abortion group calling itself the Center for Medical Progress.

Defunding Planned Parenthood would devastate the organization’s ability to provide the other 97 percent of its services.

On Friday, House Republicans passed a bill 241-187 that would defund Planned Parenthood for one year. (The bill failed in the Senate on Thursday.) But with President Barack Obama promising to veto any measure defunding the women’s health organization, and the Senate holding enough votes to block it, the bill was viewed as largely symbolic—a ploy by Republicans to score political points with its conservative base.

Ahead of a procedural vote in the Senate, the White House reissued its threat on Thursday, vowing to veto any short-term spending bill that would eliminate Planned Parenthood’s funding.

With Planned Parenthood at the center of the day’s biggest political showdown, it’s important to understand the organization and its past. Here are a few key facts about Planned Parenthood, abortion, and the political context of each that everyone should know.

1) Abortions make up only 3 percent of Planned Parenthood services

Last year, abortion accounted for roughly 3 percent of the group’s nearly 10.6 million services. According to the group’s latest annual report, it received $528 million in federal tax dollars, totaling 40 percent of its $1.3 billion budget.

The Title X Family Planning Program, through which Planned Parenthood receives its federal funding, prohibits that money from being used for abortion services. Under the Hyde Amendment, the group can only use federal Medicaid funding in abortion procedures when the pregnancy endangers the patient’s life, or when the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest. Medicaid will not pay for abortions when a woman’s health—but not her life—is at risk, even if her physician recommends terminating the pregnancy.

Defunding Planned Parenthood would, however, devastate the organization’s ability to provide the other 97 percent of its services: treatment and tests for sexually transmitted diseases, cancer screenings, contraception, and other women’s health issues.

2) Planned Parenthood and the Bush family go way back

“I’m not sure we need a half a billion dollars for women’s health issues,” Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor and 2016 presidential candidate, told an audience last month at the Southern Baptist Convention in Nashville, Tennessee. He regretted it almost immediately.

Bush told reporters later that he “misspoke” while questioning the necessity of Planned Parenthood’s federal funding. Regardless, he has called on the next president, whoever that may be, to cut the organization’s funding entirely.

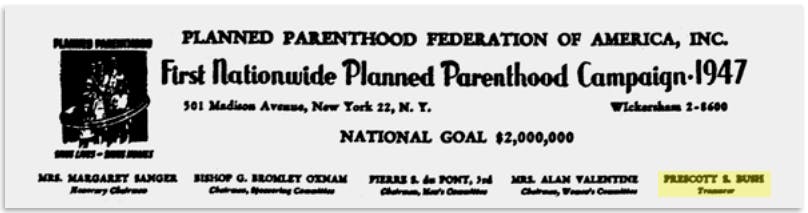

In a way, Bush’s offensive is a break from family tradition. The candidate’s grandfather, Prescott Bush, was a member of Planned Parenthood’s board prior to becoming a U.S. senator, according to a document unearthed in 1950. While in neck-and-neck race against William Benton, Connecticut’s Democratic nominee at the time, the elder Bush was outed on renowned columnist Drew Pearson’s NBC radio show as having once been treasurer of the Birth Control League. In actuality, Pearson had uncovered a document dated 1947 that listed Bush in its letterhead as treasurer of Planned Parenthood, an incarnation of the League, which had changed its name five years before.

Bush denied the charge, but ultimately lost the election to Benton—birth control being illegal at the time in the majority-Catholic state. Bush eventually became the patriarch of his family’s political dynasty, serving two terms as a U.S. Senator.

While the document inexorably ties the Bush family to Planned Parenthood’s origins, the organization’s primary function in 1947 was supplying women with diaphragms, condoms, and contraceptive jelly. More than 25 years passed before the Supreme Court’s landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which ruled that a woman’s right to privacy, founded in the Fourteenth Amendment, as well as restrictions upon state action, encompasses a woman’s decision whether to terminate her own pregnancy.

Jeb Bush’s grandfather wasn’t the last Bush to get involved in family planning. While a Texas congressman from 1967 to 1971, his father, George H.W. Bush, earned the nickname “Rubbers” for championing Planned Parenthood’s cause. In a 1968 address before Congress, he called the nation’s rising welfare costs “emphatically human, a tragedy of unwanted children and of parents whose productivity is impaired by children they never desired.”

In 1973, George Bush Sr. wrote the introduction for Phyllis Tilson Piotrow’s book, World Population Crisis: The United States Response. In it, he attributed his father’s defeat in the 1950 Connecticut election as his “first awareness of birth control as a public policy issue.”

Bush wrote:

“The population problem does not have easy answers. As a member of the U.S. House of Representatives in the late 1960s, I remember very well how disturbed and perplexed my colleagues and I were by this issue. Famine in India, unwanted babies in the United States, poverty that seemed to form an unbreakable chain for millions of people—how should we tackle these problems? I served on the House Ways and Means Committee. As we amended and updated the Social Security Act in 1967 I was impressed by the sensible approach of Alan Guttmacher the obstetrician who served as president of Planned Parenthood. It was ridiculous, he told the committee, to blame mothers on welfare for having too many children when the clinics and hospitals they used were absolutely prohibited from saying a word about birth control. So we took the lead in Congress in providing money and urging—in fact, even requiring—that in the United States family planning services be available for every woman, not just the private patient with her own gynecologist.”

3) Planned Parenthood is directly linked to the fight for women’s rights in the U.S.

The battle to liberate women and deliver them an equal voice in politics was met with more than just censure and humiliation. Many of the suffrage movement’s most prominent leaders were subjected to forced labor, beatings, and torture at hands of the U.S. government.

In January 1917, less than two weeks after founding America’s first and only birth-control clinic in Brooklyn, New York, Planned Parenthood’s founder, Margaret Sanger, and her sister, Ethel Byrne, were arrested for violating New York State law against the distribution of contraceptive information. Both served time at the workhouse on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island), made infamous three decades before by investigative reporter Nellie Bly, who infiltrated the compound and later detailed the horrors of the island’s lunatic asylum in her 1887 book, Ten Days in a Mad-House.

Byrne began a hunger strike following her arrival at Blackwell’s. On Jan. 17 of that year, after four and half days without food, prison authorities strapped her down with a blanket and forced a rubber tube into her esophagus. A feeding compound consisting of warm milk, eggs, and brandy was poured into her stomach. Byrne, whose only crime was the distribution of literature, is recognized as the first woman to be forced-fed by the U.S. government.

Byrne’s treatment was hardly uncommon. Lucy Burns, one of the most important figures in the women’s suffrage movement, is famous for spending more time in prison than out during her fight for women’s rights. Her group, the National Woman’s Party, protested daily in front of the White House. Arrested for “obstructing sidewalk traffic,” several party members—who were known as the “Silent Sentinels” because of their silent protests—were sentenced to the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia, where Burns and other suffragists initiated a hunger strike resulting in more forced-feedings.

On Nov. 15, 1917, during what is now known as the “Night of Terror,” a group of 33 women—among them Byrne and a 73-year-old woman—were beaten and tortured on the order of the prison’s superintendent, W.H. Whittaker.

4) Supporting life and abortion rights are not mutually exclusive

Abortion is condemned by the world’s most popular religions, including Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In the United States, however, Christian opposition has taken center stage.

While maternal death rates have declined dramatically over the past 150 years due advancements in medical technology, when Christianity took over as the state church of Roman Empire in the 4th century, childbirth was perilous, thanks mostly to a reliance on folklore and religious intervention, not to mention a lack hygienic awareness and surgical knowledge.

As lawmakers do today, Augustus struggled as well with the ethical predicament of terminating a pregnancy in order to save a mother’s life.

It was natural for the Nicene scholars of the day to ponder the implications of abortion. Given the high rate of perinatal death, early Christian theologians asked if the unborn deceased too would be resurrected and ascend to Heaven on the day of Last Judgement (See: Revelations). Debate rages on today over the writings of Saint Augustine, who, according to modern day theologians, differentiated between a living fetus and one that was not yet living.

As lawmakers do today, Augustus struggled as well with the ethical predicament of terminating a pregnancy in order to save a mother’s life. Early laws in the United States against abortion left room for such measures, even as abortion was outlawed in many states in the interest of “protecting women.” Such laws were rationalized—at least publicly—because of the many dangers associated with the procedure, which was often conducted with crude methods, sans antiseptic.

Historically, neither the risks associated with nor the laws against abortion have stymied its use. Past restrictions have been tied to higher death rates due to the number of women opting to undergo procedures illegally.

Nearly one-fifth of maternal deaths in 1930 were attributed to abortion, which was illegal at the time. In the 1950s and 1960s, deaths from illegal abortions ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year, according to the Guttmacher Institute, though estimates vary widely due to a lack of information prior to the nationwide legalization of abortion. The deaths of minority women due to illegal abortion between 1972 and 1974 is estimated to be 12 times that of white women.

In 1960, abortion was allowed in 44 states if the woman’s life was endangered by carrying the pregnancy to term, but only four states—Alabama, Colorado, New Mexico, and Massachusetts—and the District of Columbia permitted the procedures if the physical health of the woman was in jeopardy. The procedure was outlawed entirely in Pennsylvania, and Mississippi alone allowed abortions in cases of rape.

Establishing that there was a significant health risk due to the pregnancy, however, was not an easy task. It often required redundant examinations and hospital committee approvals. According to Guttmacher, in the early 1970s, “a licensed psychiatrist might be required to second the judgement of a woman’s doctor that an abortion was necessary on mental health grounds, or a law enforcement officer might be required to certify that the woman had reported being sexually assaulted.” Additionally, the process eliminated the possibility of an abortion for many poor and minority women who couldn’t afford it.

Today, deaths associated with legal abortion in the U.S. are extremely rare. Since Roe v. Wade, the overall rate has been less than one death for every 100,000 procedures. Only 0.05 percent of women undergoing legal first-trimester abortions suffer serious complications. Following the Roe v. Wade decision, the number of women obtaining abortions in the first trimester—as opposed to later on—rose from 20 percent in 1970 to 56 percent in 1998.

While the annual number of maternal deaths has declined significantly in the 21st century, the proportion of deaths due to unsafe abortions worldwide remained, avoidably, at approximately 13 percent between 2003 and 2008, according to the World Health Organization.

Photo via WeNews/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)