On Sunday, at 10pm PST, a gunman opened fire from the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay Casino in Las Vegas, killing 50 and injuring more than 400 in the crowd at the Route 91 Harvest Music Festival. It was yet another everyday public event rocked by tragic gun violence. It was “an act of pure evil,” according to President Donald Trump. And while this has rightfully seized the headlines, you likely haven’t heard about the other mass shootings that have taken place in the United States this year so far.

With every new mass shooting the routine aftermath follows: Discussions about gun control resurface, and critics from both sides of the debate respond. Still, not only has America failed to reduce the number of mass shootings, we can’t even agree on what a “mass shooting” is—and, in the majority of cases with multiple victims, we’ve largely ignored the violence altogether.

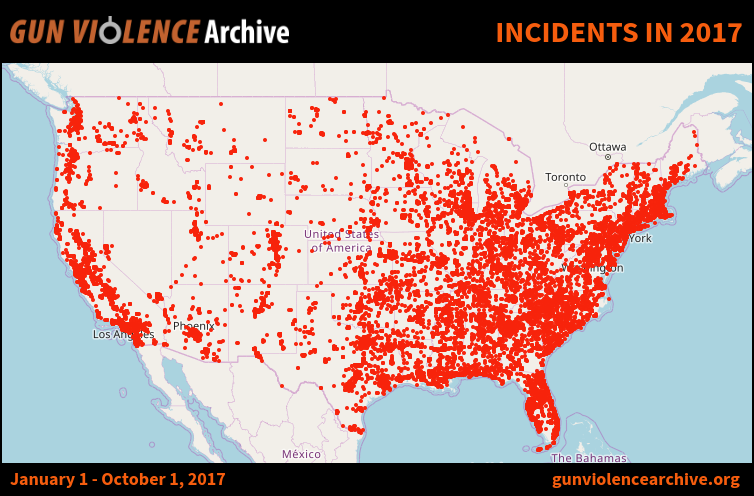

The nonprofit Gun Violence Archive (GVA) counts 29 mass shootings across the U.S. just in September, 255 since President Donald Trump took office on Jan. 20, and 273 since the start of the year, while defining a “mass shooting” as “four or more” gunshot victims, not including the shooter.

At the current rate calculated by GVA, 2017 is on track to have more mass shootings than any other year since GVA began tracking gun violence in the U.S.

On April 7, 2017, a gunman opened fire inside a St. Paul, Minnesota, home, killing 47-year-old Wade McIntosh, his 19-year-old daughter, Olivia, and 17-year-old Maria. Another woman, Anita Sprosty, was critically injured and her 18-month-old baby girl was kidnapped. Police found one of the suspected perpetrators dead from a gunshot wound nearby.

The tragedy is as horrific as any you may have seen on national news—but unless you live in the Twin Cities area, you probably didn’t hear about it until it appeared on tracking sites like GVA.

But GVA’s figures differ from those of other efforts to count mass shootings. Mother Jones‘ tally has a more restrictive definition—four or more victims killed, not including the shooter—and it only includes shootings that take place in public places, which rules out the McIntosh massacre and nearly all other “mass shootings” in the GVA database. By the Mother Jones count, 2017 has seen seven mass shootings, including Las Vegas and several other public shootings, like the Jan. 6 shooting at the Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport, which claimed five lives. The restrictive definition allows the publication’s database to put the focus on what Americans might think of as a “real” mass shooting—a lone gunman, perhaps a terrorist, indiscriminately murdering complete strangers.

The crowdsourced Mass Shooting Tracker, which began on Reddit, has the least restrictive definition: four people shot in a “single outburst of violence.” By that definition, the U.S. has seen 338 mass shootings in 2017, as of October 2. So, while the GVA’s numbers are closer to that of Mass Shooting Tracker, it’s still the closest we have to something in the middle and does not require that victims die for them to count.

Regardless of what you call four or more people being shot at one time, all available data shows that these instances of violence happen regularly and remain largely absent in national media, the vehicle through which our collective consciousness arrives at a narrative of danger. And even if you take the most restrictive definition of a mass shooting—one 2016 study counted 90 mass shootings in the U.S., total, from 1966 to 2012—it is clear that gun violence on this scale remains a uniquely American issue.

While the debate over how to address gun violence inevitably gravitates toward spats over gun control versus constitutional rights, the answer there is equally vague. And perhaps that is only logical: How can we expect to solve a problem we have yet to define and only notice when it manages, against all odds, to shock us one more time?

Editor’s note: This article regularly updated for relevance.