Jeb Bush began his political career as a firebrand soldier of the Republican Revolution.

Although he’s now widely known as the moderate Republican choice for 2016, Bush ran multiple campaigns for Florida governor while promoting the “deinvention of government” through broad privatization and the rapid shrinking of the public sector—including the transformation of the state’s prison system into a for-profit industry.

Now a national candidate facing a public much more skeptical of private prisons and harsh sentencing, Bush currently supports relatively liberal criminal justice reforms and lighter sentencing laws. In the 1990s, however, he played the conservative tough-on-crime issue at top volume.

“People now cannot walk on their streets without fear of crime!” Bush said during his 1993 gubernatorial campaign. “The simple fact is we are not safe. Not in our homes, not anywhere.”

While Florida crime had just begun a 20-year decline that continues to this day, Bush spent much of the 1990s pushing to build more for-profit prisons in the Sunshine State and around the country, with the stated dual-goals of putting as many criminals in jail as possible and saving taxpayer money at the same time.

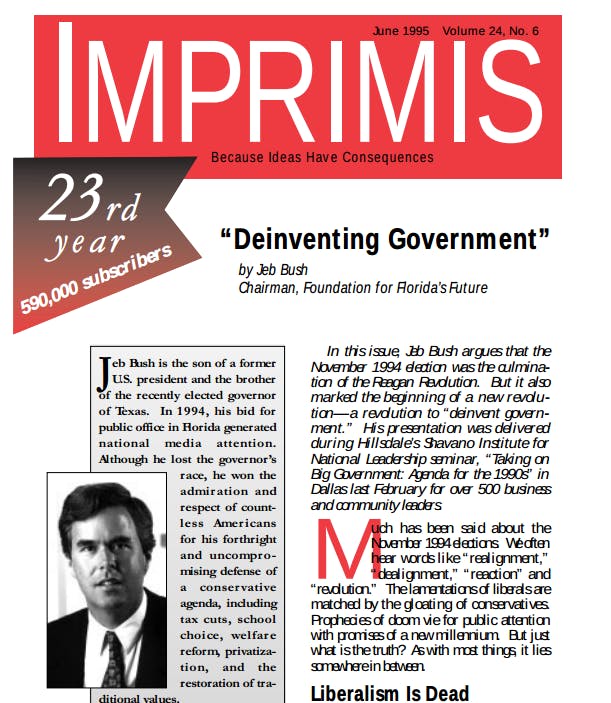

“Our criminal justice system is also an obvious target for privatization,” Bush wrote in a 1995 essay in Imprimis, an influential conservative publication. “Our prison population has doubled in recent years, and we are spending billions of dollars on prison construction and operation each year. But, according to a number of independent estimates, partial privatization could save an incredible sum—as much as 10-20 percent.”

In fact, Florida’s private prisons have notoriously had trouble reaching even the state-mandated 7 percent savings at several institutions.

Across the country, evidence that private prisons deliver any savings to tax payers at all is mixed at best, according to studies by the Government Accountability Office, the National Institute of Justice, and the University of Utah—even as the industry grew rapidly in size and wealth in the 1990s and 2000s.

They make their money in a variety of ways including running an “offender-funded” system charging mostly poor prisoners and probationers increasing fees (a “surveillance fee” for electronic bracelets sometimes put on for petty offences, for instance) that either don’t exist under a public system, are paid for by the public, or are just significantly higher under a for-profit firm.

When fees can’t be paid, there’s a privatized jail cell waiting even for petty offenders. That looming cell drives many offenders to commit illegal acts in order to pay fees to the companies and court, fueling a bizarre circle that in the end profits private prison firms, as a recent New Yorker article chronicled. This cycle severely undercuts the industry’s public claims that the companies focus on rehabilitation of offenders.

Prison riots across the country, including in Florida, have led private prisons to be dubbed “Gladiator Schools” because the violence taking place inside them can so vastly outweigh their public counterparts. The riots have had various catalysts, including prisoner protests for better “medical [care], programs, clothes” and respect from prison officials, complaints backed up by an FBI agent.

By 2010, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and the GEO Group—the country’s two largest prison companies—reported $2.9 billion in combined revenue.

Bush was hardly alone in aggressively pushing private prisons, especially as a nascent conservative during the culture wars of the ’90s.

The private-prison boom came quickly in the wake of president Richard Nixon’s war on drugs. Harsher sentencing laws led to an explosion in incarceration rates and rising costs almost immediately thereafter. The U.S. now has the highest prison population on earth.

Between 1990 and 2009, private prisons took on 1,600 percent growth in prisoners, according to the federal government, due in large part to the industry spending millions of dollars on lobbying and employing hundreds of lobbyists throughout the country—including dozens in Florida alone.

On top of building for-profit prisons, Bush championed legislation that made sure the institutions were filled to capacity.

Bush boasted about his “get tough on crime” attitude on the campaign trail. When he came to office, he championed numerous landmark mandatory sentencing laws that passed early on during his first term.

In this effort, Bush was closely aligned with the goals of the private-prison lobby during his time as governor.

A little-known but widely influential organization called the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is among the country’s most ardent supporter of mandatory sentencing laws. It’s also been financially and politically supported by the prison industry’s biggest companies, some of which have been official members of the council.

ALEC writes “model legislation” advocating harsh sentencing and detention laws that its members—thousands of whom are elected officials—then introduce and pass into law around the country.

Bush pushed for and passed harsher laws, like three strikes legislation and “truth in sentencing,” that an ALEC Task Force Director bragged was “based on an ALEC model bill.”

All of these laws increase the number of prisoners, increase sentences, and increase the amount of money private prisons earn in the process.

Over the course of the last two decades, the private-prison industry has spent millions on contributions to Floridian politicians, including hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Republican party during Bush’s tenure.

While crime in Florida declined in the 1990s, Florida’s prison population doubled yet again, to nearly 80,000 prisoners as sentencing rules became harsher.

Bush’s second campaign for governor was successful and he served the office from 1999 to 2007. During that time, the same trend continued: Crime fell and Florida’s prison population rose to over 100,000 for the first time in history, half of whom were black. African Americans make up about 15 percent of the Florida population. Similar sized states like New York had reduced their prison sizes during the same period.

At the end of Bush’s tenure as governor, half of Florida’s prisoners were nonviolent drug and property offenders, according to the Sentencing Project.

While in office, Bush did soften his stance somewhat on the wholesale privatization of Florida prisons. As a political and financial battle raged between the public and private prison sectors in the state, Bush backed off privatization in some cases if it led to the loss of union jobs, a position that won him the support of the state’s Police Benevolent Association.

As for shrinking government and saving money, Bush repeatedly raised spending on Florida’s corrections budget during his two terms as governor. In 2007, when Bush left office, it cost Florida over $979 million to imprison the nonviolent drug and property criminals of the state.

Florida overpaid CCA and GEO by $13 million, a 2005 audit showed, including for jobs that were never filled and maintenance that was never performed.

Both companies were paid $90 million annually despite audits showing the prisons weren’t being run as efficiently as state law required, the St. Petersburg Times reported.

Nationwide, the industry’s profits have gone up close to 500 percent since Bush first wrote about “deinventing government.”

Neither Bush nor Bush’s spokesperson responded to our requests for comment.

The profits of private prison companies, by their own admission, rely on high incarceration rates: “The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices,” according to a 2010 annual report by the largest private prison company in America, the CCA.

Private prisons, which are viewed unfavorably by the American public, have been subject to especially pointed criticism in recent years.

“The evidence that private prisons provide savings compared to publicly operated facilities is highly questionable, and certain studies point to worse conditions in for-profit facilities,” according to a 2011 research paper by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). “The private-prison industry helped to create the mass incarceration crisis and feeds off of this social ill. Private prisons cannot be part of the solution—economic or ethical—to the problem of mass incarceration”

As the last two decades have seen the rise of online political activism, opponents of private prisons, like the ACLU, have aggressively leveraged the Internet to spread their message.

While Bush may have made his case for private prisons in the pages of Imprimis back in 1995, the conversation has since moved online, where, videos and research on the industry have found a wide audience—a factor every 2016 hopeful must now take into consideration when exploring the things they said, and how they acted on those promises, long ago.

Although Bush is now fighting to center his image and appeal across the political aisle, his early political career gives valuable insight into the foundations of the man now campaigning for president.

“I’m a hang-’em-by-the-neck conservative,” Bush said in 1984, shortly after taking his first political job campaigning for his father. Would he stand by such a line today?

Illustration by Max Fleishman