The hundreds of thousands of impassioned people in the streets of Hong Kong have been called the most high tech protest movement of all time. So why are they using insecure and opaque software to communicate?

Watched over by the famously information-greedy Chinese government, protesters turned to a peer-to-peer messaging app called Firechat that works over Bluetooth (instead of 3G or 4G) so that it circumvents the Internet entirely. Utilizing the app, phones are supposed establish direct connections, sidestepping standard censorship and surveillance.

Already battle tested during contentious unrest in Taiwan, Iran, and Iraq, Firechat spread rapidly this month in Hong Kong and has been trumpeted by the Western press as the driving power behind the protest.

But Firechat’s honeymoon period is coming to a close. Not only does it have major security issues, it’s also being criticized as lacking transparency by programmers who believe that open software is the best solution to protesters’ problems.

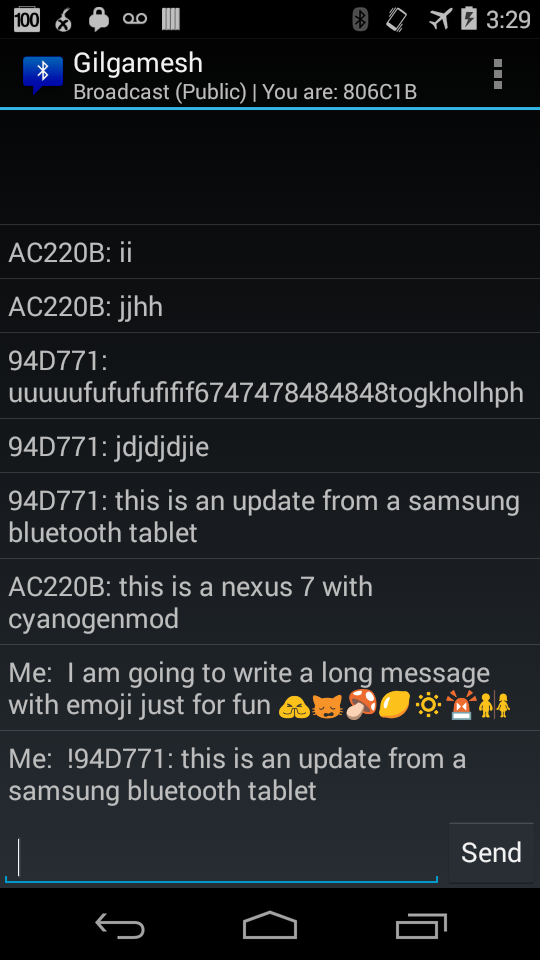

Not one to sit back and passively complain, Nathan Freitas, a developer and activist already well-known for his security work for human rights activists, has built a free and open alternative called Gilgamesh, or Gilga for short. It’s designed to be a decentralized, censorship- and surveillance-proof version of Twitter ideal for modern protest movements.

Inspired by the funny Wifi names that dot so many neighborhoods around the world, Gilgamesh uses a smartphone (or computer)’s Bluetooth device name to broadcast messages up to about 240 letters long to anyone within distance. Your device name becomes a Twitter message that can share information during crises.

“You can set a message like ‘!Gather 7pm at 1st and Main’ or ‘#Legal aid is 2125551212,'” Freitas, a developer and activist already well-known for his security work for human rights activists, wrote in his announcement. “If people like what you have written, they can change their status that message, and rebroadcast another 30 feet in whatever direction they are headed. Again, it is basically Twitter combined with doing ‘the wave’ at a football game, except the wave is powered by these little super computers+radio stations we have in our pockets.”

At its most basic, the hack doesn’t require an app—on the simple end of the spectrum, you can go change your Bluetooth device name and start broadcasting right now—but Freitas built a small, open-source one (which you can find here) to make everything as powerful, secure, and easy as possible.

Freitas’s work began because he was “frustrated by the closed, murky, proprietary nature of FireChat,” he wrote.

“I wanted to find a simple way to answer the question ‘what do we do when the Internet goes away’ problem,” he blogged. “FireChat is clearly not the answer for the types of communities I am trying to help, but in its absence, we have no other solutions, it seems.”

Freitas has a list of top priorities with the new app. Gilgamesh—which, it must be said, is still very new and under development—has a potentially long list of advantages over Firechat.

First and foremost, the new app is open-source, so it can be looked at and reviewed by anyone. Trusting a small centralized company is not a part of the equation.

Gilga also requires no user registration, so there is no central user registry for authorities to view. But unlike Firechat, where user impersonation is a major issue, impersonation is challenged by simplifying device ID numbers to six digits and adding an asterisk when users are directly paired, and thus trusted.

Perhaps just as important, Gilga can encrypt private messages between users, stymying the surveillance that typically plague major protests around the world.

Gilga stores no data permanently and makes it easy to broadcast to everyone in the vicinity. Freitas described a “fire and forget mode, where the user can enter a message, put the phone in their pocket, and walk around and area and have it broadcast to all devices it encounters” with “as little user involvement as possible.”

But the app, Freitas readily admits, is far from perfect.

“There are risks about Bluetooth device IDs being scanned and logged, impersonation attacks based on modified Bluetooth radios, and the same misinformation spreading we see whenever we have an open commons, be it FireChat or Twitter,” he wrote. “We have some ways to combat that, but it will be hard. My hope is that, by doing this work in the open, and with contributions by brilliant minds like yours, we can come up with some additional breakthroughs.”

Photo via Citobun/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)