When Tinder launched in 2012, it started a revolution. It was the antithesis of sites like Match and OkCupid, which feature labor-intensive profiles that delve into your most personal sexual kinks to your feelings on abortion. Instead of having to consider the other person’s psyche, Tinder introduced the online equivalent of looking someone up and and down and deciding if you’d have sex with them.

But with this superficial approach to dating came a whole host of cultural land mines. By blatantly selecting who and what we find physically attractive, a discussion was borne about why we find what we find physically attractive.

And there are patterns. In 2014, OkCupid found that 82 percent of nonblack men showed a negative bias against black women. Christian Rudder, co-founder of OkCupid, told NPR that year, “Black users, especially, there’s a bias against them. Every kind of way you can measure their success on a site—how people rate them, how often they reply to their messages, how many messages they get—that’s all reduced.”

Brian Gerrard, the co-founder of Bae, a Tinder-like app for black singles, agrees. “It sucks to be black on a mass-market dating app,” he told the Daily Dot via phone.

Apps like Tinder “weren’t created with us in mind,” says a co-founder of Bae.

Gerrard, 27, recalls observing in astonishment the differences between the experiences of a black friend versus a white friend on Tinder. When the men, of equal attractiveness and success, each swiped right on 50 women, the white friend got 45 matches while the black friend got five. The black friend messaged all five matches and got just one reply. Meanwhile, the white friend reached out to a few women, received messages from a few women he never pursued at all, and then chose which conversations he wanted to move forward with.

That’s when he had a realization: Apps like Tinder “weren’t created with us in mind.”

For Gerrard and his co-founders, Bae is not about shutting out users from potential mates of varying races, but about creating a space where users don’t need to worry about being the target of casual racism.

And on Bae, it’s not just black men or women looking for a fellow black match. Gerrard reveals that 20 percent of Bae users are nonblack, which allows those who aren’t exclusively looking for black singles to still have an open mind. In a way, it’s achieving something similar to the Tinders and OKCupids of the world by exposing black users to people from diverse backgrounds who they might not meet in real life, while knowing that nonblack people are there, not to exclude black people, but to meet them.

Or, as Gerrard put it, “everybody on Bae is looking for black women.”

Sonya Kreizman and Natasha Nova founded a similar safe space for Jewish men and women. Their company, Crush Mobile, launched JCrush in 2014 as the modern alternative to its ancestor JDate, whose online dating model can feel antiquated for the modern dating app user. They too drew on a shared experience of looking for someone from their own culture in a vast sea of choices.

“We wanted to see if the concept of targeting niche demographics would work, and the Jewish [population] was easier because we’re Jewish and have a big network,” Nova, 35, said when she and Kreizman, 30, recently sat down with the Daily Dot. “So we decided to just throw it out there, and we didn’t expect what we saw.”

Within its first year, JCrush had more than 100,000 users, proving targeting specific demographics had its value. So in 2015, the pair set their sites on a much larger population—Latinos—launching MiCrush.

While neither Jewish woman could begin to understand the experience of being a Latino man or woman online, anecdotal evidence from friends proved the need for a safe space similar to Bae’s. “I have a girlfriend who’s Puerto Rican. She said, ‘Do you know it takes me 20 swipes to find a match on Tinder?’” Kreizman recalled.

Now MiCrush is a dominant player in markets all over North America and Latin America. According to the company’s data, MiCrush has 350,000 users who have made 150M swipes, 10M messages, and 1.5M matches in its first few months of existence.

With such a huge audience sample, Kreizman and Nova said they are finding that Latinos are very much interested in dating within their community. But even within that community, division exists. One feature allows users to select specific countries of origin for their matches.

In other words, if you’re Colombian and looking only for other Colombianos, it’s possible to do that—and make your dating world even smaller.

So the obvious question remains: Are race-targeted apps giving us the specific characteristics we seek in a partner, or are they making us even more single-minded about getting exactly what we want?

“Ultimately, each one of our own individual choices is profoundly informed by the community we grow up in, perhaps by the relationships we had with our siblings or parents,” Eric Silverberg, the co-founder of Scruff, a Tinder-like app for gay men, said in an interview with BuzzFeed earlier this year. He also noted that those individual choices mean “sometimes they have height/weight preferences, sometimes people have body hair preferences.” And sometimes they have “ethnic preferences.”

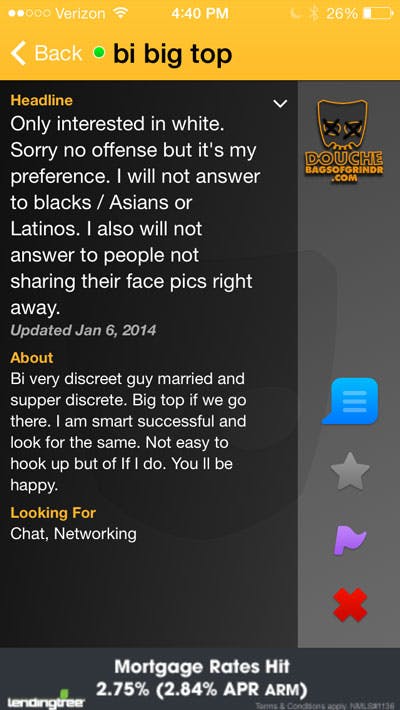

A September 2015 story in Alternet called “The casual racism of our most popular dating apps” offers a more pointed take on the current online dating climate, saying it has encouraged a culture of bigotry. Writer Carrie Weisman cites a blog called Douchebags of Grindr, which is exactly what it sounds like, with screenshots of dating profiles that are less than nuanced.

“One reads, ‘Not looking for Fat. Old. Or anything but White,’” Weisman writes. “Another states, ‘I love men from different cultures. Just no Asians. I’m not racist.’” On Grindr, the most popular gay dating app, users easily and often state their ethnic or religious preferences, with no deference to the people belonging to these groups.

In some ways, you could say online dating was destined for niche apps; tech entrepreneurs are conditioned to give people what they want, often catering to very specific whims, whether they challenge our ingrained biases or not. There’s an app to order food 24/7/365; an app that literally allows you to rate other people; another that will feed your dog. But just because people want a dating service that eliminates the matches they deem undesirable, does that mean we should give it to them?

For some of the dating app founders, the challenge in creating a culturally targeted app has been authenticity. While Kreizman and Nova don’t seem like the most logical choice to launch a Latino-centric app, they understood early on the importance of consulting with someone who has intimate knowledge of the culture.

One of the co-founders of Crush Mobile, Javier Soto Muñoz, was born and raised in Puerto Rico, which happens to be one of MiCrush’s top five markets. Kreizman says their success has hinged on having “someone speaking to the community in the same language.”

Bae, on the other hand, is the first of this genre of “swipe right, swipe left” that’s created for black people by black people. Gerrard points to Soul Swipe as Bae’s closest competitor, but the difference is that Soul Swipe was founded by a Jewish guy in Los Angeles. He says that black singles haven’t reacted in the same way to the earlier app as they have to Bae, which he says gained more users in its first two weeks than the general-population app Hinge had in its first year and half.

Bae launched at a Howard University basketball game last year, with a marketing expense of $140. Invaluable to Bae’s success has been customized and culturally relevant push notifications like “Janelle sent you a message, hit her hotline bling before she gets home” (a reference to the popular Drake song).

“When you’re ready for a serious relationship, you’re going to look for someone from a similar culture as you.”

Kreizman also sees that there are inherent differences to the way MiCrush and JCrush users approach dating. The designs of MiCrush and JCrush are basically the same, with slight tweaks to aesthetic. Both allow users to send stickers, photos, and song clips via Spotify to matches, but data has shown that MiCrush users are utilizing these visual and aural features far more.

“It seems every community wants an app because it’s going to make their lives a lot easier,” Kriezman said. “Tinder is so global. When you’re ready for a serious relationship, you’re going to look for someone from a similar culture as you.”

But Gerrard’s idea of what it takes to be in a serious relationship is disparate from Kriezman’s, and perhaps from the niche dating app industry’s in general. In his mind, despite the fact that he’s helped create a wildly successful targeted app, the quest for love is universal—and it has nothing to do with whatever race or religion you’re born into.

“I would encourage people to make their decisions about love,” he says. “At the end of the day, it has nothing to do with looks. At the onset it may, in terms of initial attraction. In terms of meaningful relationships, those go way beyond physical appearances.”

Essentially, he believes, superficial people are superficial. The dater who is vehemently opposed to people of color are likely to hold other impossibly high physical and personal standards for their significant other, which will not help them find a lasting union.

His best advice can apply to the most niche of sites, like Farmers Only, or to a single swiping through Tinder on a Saturday night. The advice: Swipe right.

“The worst thing that happens when you swipe right is a match.”