Opinion

The men knocked down by last fall’s wave of sexual misconduct allegations have now had a few months’ worth of distance between themselves and the headlines. As such, here they come, creeping into the public eye once again.

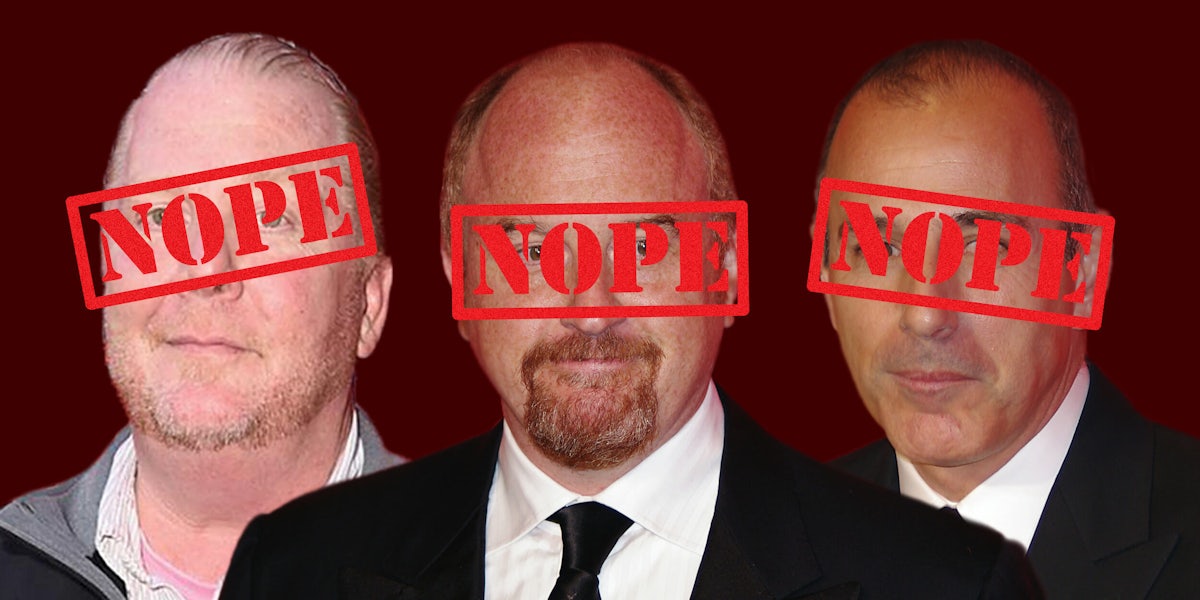

Matt Lauer and Louis C.K., two of the most famous to face allegations of habitual sexual misconduct, have recently been spotted out and about, and various media outlets have interpreted their sidling back into sight—if not necessarily our good graces—as a harbinger of comeback tours to come. Tom Ashbrook, the host of NPR’s On Point until he was fired in December for having cultivated what many employees saw as an abusive work environment, asked point-blank in a Boston Globe column if he could come back now, please.

“Is there room for redemption and rebirth, in our time of Google trails and hashtag headlines?” he wrote. “I hope so.”

As writer and podcaster Sarah Lerner put it in a viral tweet, “We’ve reached the sexual predator redemption arc phase.”

https://twitter.com/SarahLerner/status/986451183999963137

And I, for one, am not particularly jazzed to be here.

#MeToo toppled many many men accustomed to abusing their power, exploiting their colleagues, committing sex crimes, and getting away with it all—even profiting from their deplorable behavior. Rather than really explaining themselves, they retreated to their celebrity safe houses and hunkered down for however many months they believed it would take the storm roaring outside to quiet down. They left behind apology notes that uniformly failed to suggest sincerity; few included the words “I’m sorry,” and those that did came with caveats.

For example, one notable mea culpa surprised with the inclusion not only of the words “I’m very sorry,” but also “I apologize”: Mario Batali’s. The celebrity chef’s apparent pattern of sexually aggressive and coercive behavior—including forcing himself on a woman in the Spotted Pig’s so-called “rape room”—came to light in December; in response, he admitted that there were “no excuses” for his actions and took “full responsibility.” He then undercut the legitimacy of those sentiments by tacking on the recipe for his pizza dough cinnamon rolls, a perennial “fan favorite,” he quipped.

Immediately, networks took deals off the table and retailers pulled Batali’s products from their shelves: His culinary empire began to crumble. According to a New York Times report from early April, though, Batali has recently been setting meetings with people he trusts to tell him how to nudge his career back on track. Having passed the intervening months since the allegations surfaced “examining his blind spots,” to borrow the Times’ phrasing, Batali “is simply trying to learn to be the wallpaper in the room and not the room itself.” He is also trying return to work, even though the toxic culture he helped establish apparently hasn’t changed much in his months off.

Meanwhile, Matt Lauer reared his head in a Manhattan restaurant last week, prompting speculation from Page Six that the disgraced ex-Today Show host is “ready to restart his life” and “testing the waters for a public comeback.” NBC fired Lauer in November, just before news broke that multiple women had accused him of sexual harassment and assault on the job. In the aftermath, his marriage disintegrated, and he holed up in the Hamptons where he has presumably been licking his wounds for the past five months. I say that because, despite his apology statement’s promise that he would embark on a solo “soul-searching” journey as his “full-time job,” its actual language rang hollow.

“There are no words to express my sorrow and regret for the pain I have caused others by words and actions,” he wrote. “To the people I have hurt, I am truly sorry.” Acknowledging that “there is enough truth in these stories to make me feel embarrassed and ashamed”—two things a person should feel when they allegedly have an office-door-locking button installed on their desk to aid in the trapping of female coworkers—he did not fully own up to the pile of accusations tendered against him. “Some of what is being said about me is untrue or mischaracterized.” But where exactly the lies were, he didn’t say.

At least he said sorry, though. The same was not true of comedian Louis C.K.’s statement in the wake of a November New York Times article detailing his long-running practice of cornering women and making them watch as he masturbated. Although he admitted that the stories were true, he conspicuously omitted the magic words. “At the time, I said to myself that what I did was okay because I never showed a woman my dick without asking first,” he wrote. “But what I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them. The power I had over these women is that they admired me. And I wielded that power irresponsibly.”

C.K. largely disappeared from public life but was recently spotted in the cafe above the Comedy Cellar in New York. That appearance was enough to prompt the Hollywood Reporter to wonder not if but when we can expect a C.K. comeback. Seeking to determine the best possible way for the comedian to step back onto the stage, writer Stuart Miller sourced most of his insights from other male stand-up comics—a group that, as a whole, does not exactly inspire confidence when it comes to demonstrating respect for women—and a couple of women in comedy and entertainment. Their “consensus” held that C.K. had behaved badly, sure, but not as badly as Harvey Weinstein. He did not deserve a life term, one guy said, while others suggested a heartfelt apology might help C.K. ingratiate himself again—an idea so commonsense it should go without saying. Yet here we are.

Louis CK’s redemption should come from working with other male comics to showcase the funny women they’ve stepped on for decades.

— Miriam “Peekaboo” Heddy (@miri_iron) April 18, 2018

When we are very small, adults put us in time out as punishment for bad behavior, with instructions to think about what we did wrong. I don’t imagine many of us five-year-olds spent those stretches in silent introspection; rather, I expect the majority of us passed the minutes braiding our shoelaces together or making up mental games or thinking about how we could best pantomime remorse, shorten the sentence, and get back to playtime. Apologies offered thereafter were sometimes sincere, more often perfunctory. This feels like the latter.

I understand the desire to return to a normal life, especially when your normal was shiny, hyper-privileged celebrity; I’m not suggesting shitty men should be eternally banished to a trash island, although I think about that glittering dream from time to time. But I do believe that patterns of serial predation will continue to play out forever as long as the perpetrators fail to grasp the reasons why their misdeeds were wrong, both in terms of big picture morality and the cultural nuances that contribute to systemic inequality. The world continues to spin without these men’s contributions, and I am not prepared to accept an apology quite yet, even if they were prepared to actually give it.

Securing forgiveness requires giving people reason to believe you won’t do the bad thing again, because you understand why it was bad, hurtful, damaging, destructive, et al., and you don’t want to place yourself or others in that position anymore. It requires owning up to your mistakes without hedging. Maybe if these apologies had been real; maybe if these men had not attempted to mollify us with pastries and instead paused for a moment of legitimate reflection, then put out statements that clearly demonstrated authentic comprehension of and culpability for their errors (or crimes, whatever you want to call them); maybe if they had actually said sorry, full stop, we could begin to talk about redemption. But they haven’t.

The redemption tour of Lauer or C.K. or Batali will not likely include a segment in which they sit down with their accusers and actively listen to the emotional and professional damage their actions have wrought. It probably won’t include a remedial course in respecting other people, either. In any case, I would imagine that the process of unlearning over five decades’ worth of experiential lessons that led you to believe you can somehow harass and assault with impunity would require more than five months of a staycation. You have to give people reason to forgive you. And so far, all I’m seeing are self-serving efforts to sneak back to the way things were.