Opinion

What happens when a woman calls out a popular “woke” celebrity for reportedly, continuously ignoring consent? People come to his defense, apparently. Then they strike out against the #MeToo movement.

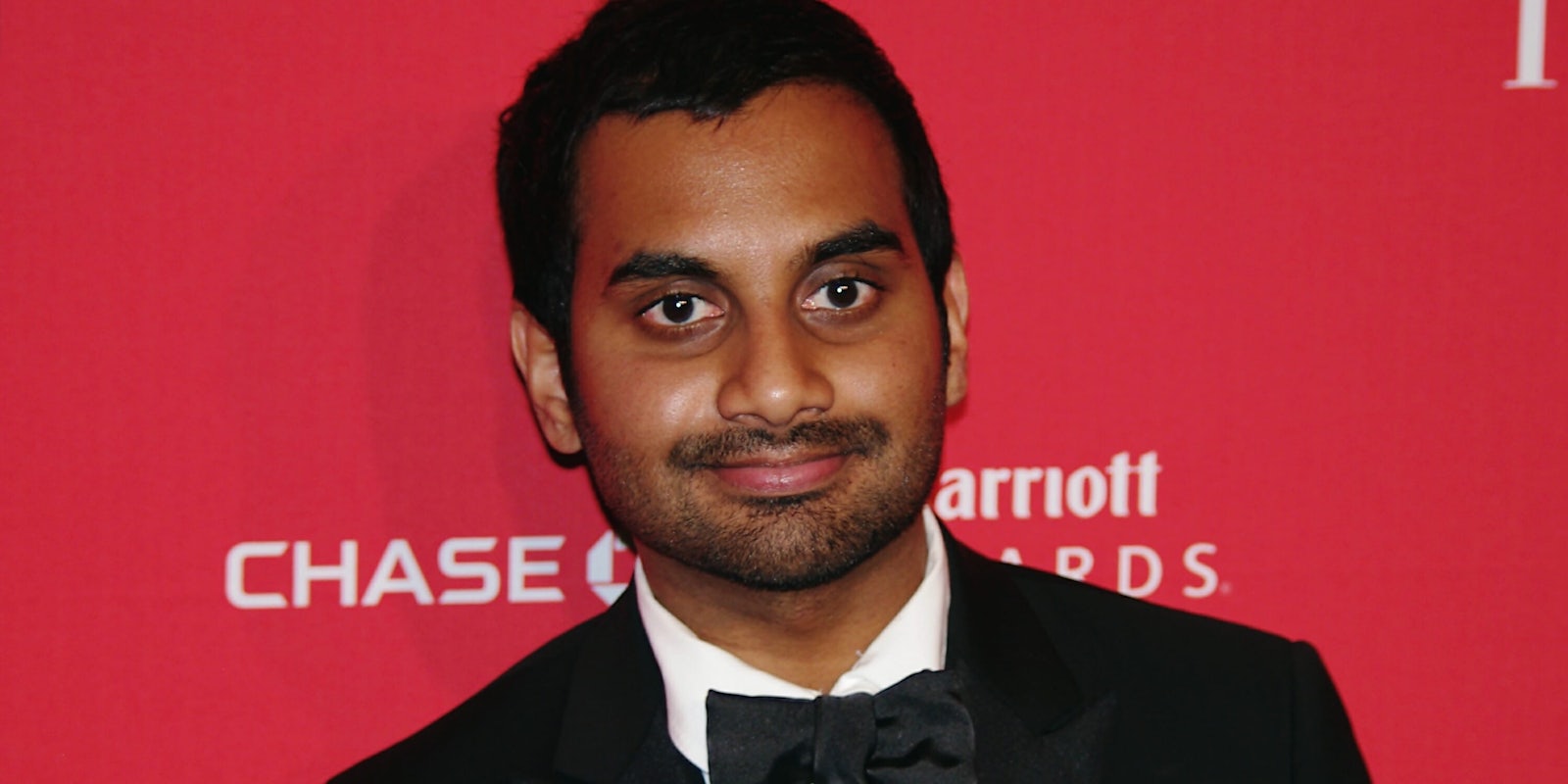

#MeToo received some hefty pushback in op-eds and Twitter takes this past weekend after online magazine Babe published an article in which a woman named “Grace” accused Aziz Ansari of sexual assault. While numerous feminists have since argued that Ansari’s alleged behavior reflects the same experiences that many women have dealt with while dating men, not everyone is coming to Grace’s defense. Instead, some blame Grace, implying that she could have done more to stop Ansari from allegedly assaulting her. Some, like New York Times’ opinion editor Bari Weiss, are arguing Grace just had “bad sex.”

“The insidious attempt by some women to criminalize awkward, gross and entitled sex takes women back to the days of smelling salts and fainting couches,” Weiss, a self-identified feminist, claims. “That’s somewhere I, for one, don’t want to go.”

Weiss isn’t alone; some of Ansari’s biggest defenders are women—albeit white, cis, able-bodied, likely privileged women. Over at conservative website the Federalist, writer Abigail Shrier has some choice words for women who advocate for consent, now largely lumped in as #MeToo supporters. Particularly, she thinks the movement is killing American sexuality.

“When I was in my twenties and still dating, the quickest way a suitor could ruin things was by asking permission to kiss me,” Shrier writes for the Federalist. “A request at once so innocuously sweet, so harmless and timid and proper, it practically begged for refusal.”

https://twitter.com/mattyglesias/status/953081487288688641

https://twitter.com/g_bluestone/status/953288493593133056

Shrier insists that it’s more important for men to show their worth and “fearlessness” than ever talk about sex, and Weiss puts the burden on women to do all the talking. In fantasy, that kind of sex might sound fun to some. But reality is much more complicated than sexual daydreams.

When sex is considered something that seamlessly happens without ongoing communication between two (or more) parties, then sexual relationships downplay consent’s role during sex. And when #MeToo’s critics argue that a lack of communication means the victims are to blame, they shift responsibility away from predatory men and back onto the victims. This is exactly what #MeToo is fighting against—and why it’s a threat to critics who don’t want to move the culture forward.

Rethinking how we have sex

Chances are, you’ve heard the term “rape culture” before. Marshall University describes it as “an environment in which rape is prevalent and in which sexual violence against women is normalized and excused in the media and popular culture.” Rape culture argues that consent is boring and sexual conquests are exciting. It argues women are to be pursued aggressively—women like that pursuit, especially if they dress a certain way and show interest at any point. It doesn’t matter if they change their minds and show signs of discomfort or refusal.

Suffice to say, through rape culture, Western society carries unrealistic baggage dictating how men should have sex.

For many feminists, Babe’s report depicts rape culture in action. After multiple attempts to allegedly seduce Grace, Grace says she told Ansari that she felt “forced” into having sex, which Ansari reportedly acknowledged, saying, “It’s only fun if we’re both having fun.” But soon after, Grace says he proceeded to ask her to go down on him, essentially ignoring her discomfort. He repeatedly forced her hand to his crotch too, Grace says, and even though she kept pulling away, he repeatedly initiated.

“He sat back and pointed to his penis and motioned for me to go down on him,” Grace told Babe. “And I did. I think I just felt really pressured. It was literally the most unexpected thing I thought would happen at that moment because I told him I was uncomfortable.”

A lot of sexual assaults look like Grace’s story. As Guardian columnist Jessica Valenti points out, sex is often perceived as a pursuit by men for women, a battle that ends in sexual intercourse if the man wins. Instead of seeing women as individuals that have the right to say “yes” or “no” to sexual behavior, straight men think sex comes down to dogged perseverance until a woman finally caves.

“The idea that partners should always be enthusiastic participants goes against everything we’ve been taught about sex,” Valenti wrote in a Twitter thread this past weekend. “The biggest, most complicated hurdle is finding a way to hold men to account while also understanding that many of them feel they’ve been following a normal sexual script.”

https://twitter.com/JessicaValenti/status/952568652066443264

https://twitter.com/JessicaValenti/status/952569422459363329

https://twitter.com/JessicaValenti/status/952571955458334720

When sex is a pursuit, and female bodies are conquests to be won, men, like Ansari in Grace’s account, seem to think it’s fine to repeatedly initiate sex until they “win.” This may be seen as “normal” behavior, but just because it’s common doesn’t mean it’s right or respectful or non-violating. For many women who experience this kind of coercion, it’s debilitating in the moment and traumatizing in its aftermath. And as Babe implies, Grace’s alleged discomfort should have been enough for Ansari to call things off.

“Last night might’ve been fun for you it wasn’t for me,” Grace says she later texted Ansari. “When we got back to your place, you ignored clear non-verbal cues; you kept going with advances. You had to have noticed I was uncomfortable.”

In his response to the allegations, Ansari publically said: “It was true that everything did seem okay to me, so when I heard that it was not the case for her, I was surprised and concerned.”

How revolutionary it would have been if had thought to be concerned when he was actually having sex with her.

Consent is affirming

If sexual advances are cultural scripts, and men feel like they can only have sex by engaging in a certain kind of domineering sexual role without concern for the woman they’re having sex with, then Grace’s take on her encounter with Ansari sheds a lot of light onto how we think about sex. Clearly, something needs to change.

Hence how we came upon #MeToo.

But change seems unlikely when some people refuse to acknowledge the problem, and then try to shut down the movement that’s calling it out by insisting it’s over. In the New York Post, known controversial columnist Andrea Peyser argued #MeToo has “officially jumped the shark” because “decent, sensitive, feminist men” like Ansari are under fire. Peyser went on to argue that, because Grace allegedly didn’t communicate enough with Ansari, by definition, Ansari didn’t commit sexual assault.

“This is how a blameless man was swept up in a witch hunt. And it scares me,” Peyser writes for the Post. “These are not the words of a predator, but of a man trapped in an Orwellian nightmare. #MeToo has ensnared an innocent man.”

But Peyser refuses to acknowledge that the Ansari Grace describes is not “blameless.” Peyser is not “listening” to Grace’s story, nor is she listening to all the women who have literally said, “Me too, I have experienced this kind of assault.” If she was reading and listening carefully, she would see that Grace’s account shows that Ansari had plenty of opportunities to successfully read the room. Grace says she repeatedly resisted, moved away, or otherwise asked Ansari to slow things down and “chill.” Even if Ansari hypothetically had missed all these clues, then he should’ve checked in on Grace, maybe looked her in the eyes, and made sure she was indeed having fun. This is what women are saying they want, what they say they have always wanted—to be respected, to be shown kindness, to be treated as if they matter.

Men need to work on reading signals from their partners. They need to initiate conversation if their partners are silent. And if men keep missing signs of distress or discomfort, then they need to learn how to read the moment, talk things out, and communicate.

“What we can urge is that men learn to be more adept at communication and consent, especially when it’s non-verbal,” Daily Dot’s Lauren L’Amie writes. “Watch and listen and understand your partners in sex and relationships, men. Ask if something is OK. Stop when it isn’t. Practice honesty and caution and empathy.”

I saw someone tweet something like “if what Aziz Ansari did was sexual assault then every woman I know has been sexually assaulted” and like yeah, actually.

— Arnesa Buljušmić-Kustura (@Rrrrnessa) January 15, 2018

Aziz Ansari is not a rapist. He did not sexually assault Grace in the way that we’ve traditionally understood sexual assault. However, his refusal to hear his date’s hesitance to have sex is a violation and crosses a boundary that many men have traipsed over.

— Evette Dionne (@freeblackgirl) January 16, 2018

if you truly think the aziz ansari story in any way discredits the larger #metoo movement, then you were just looking for an excuse and any one will do.

— Joel D. Anderson 🆓 (@byjoelanderson) January 16, 2018

Peyser and Shrier essentially argue that concern and interest in a woman’s comfort isn’t something that should be expected of men. Responsibility falls on women’s shoulders to boldly speak up at all times. Even Weiss argues the “bad sex” comes from women being too timid to speak up for themselves.

But this isn’t about bad sex. It’s about assault. This isn’t about what women need to do to be better victims. It’s about what men can do to ensure they don’t harm women. If the culture around sex needs to change, that means the practices men have inherited need to go away, too. When Americans believe sex is something that happens seamlessly and is won through persistence, then every woman in the U.S. is susceptible to sexual assault. And that means every man could be a perpetrator, too. Even if he appears to be one of the good ones.

This is the conversation that #MeToo has brought out into the open, so to deem it “over” is a transparent rouse to wish it away. It’s obvious—by the quick, defensive reactions the movement has illicited—that this is only the beginning of the work it will evolve to do.