Analysis

For the past three weeks, our nation has been embroiled in an ongoing dialogue about the pervasive and brutal nature of racism in our society, and the question of who is responsible for upholding this unjust system has arrived at the doorstep of many female CEOs. This could have been an opportunity for a new kind of leadership to emerge. Unfortunately, when faced with criticism, these women, many of whom have built their brands under the moniker of “feminism,” haven’t used their power to rally meaningful support, nor have they engaged in sustained public reflection about how they can do better. Instead, their response, largely, has been to quit.

As n+1 editor Dayna Tortorici so succinctly put it on Twitter, “The purge of the girl boss is upon us.”

Indeed, this past week saw a mass exodus of young, hip female leadership. On June 10, Ban.do co-founder Jen Gotch stepped down from her role as the Los Angeles-based brand’s chief creative officer. Later that evening, Man Repeller founder Leandra Medine Cohen announced via Instagram that she would be “stepping back” from the brand to let her employees show their audience what the brand “could be” without her at the helm. The following morning, an email surfaced announcing co-founder and CEO Audrey Gelman’s resignation from “women-centered” coworking and networking space The Wing. Finally, on June 12, after weeks of criticism for tone-deaf imagery and severe mistreatment of staff, Yael Aflalo resigned from her role as CEO of Reformation, a brand built on the promise of “sustainability,” and images of long-limbed women in floral maxi dresses.

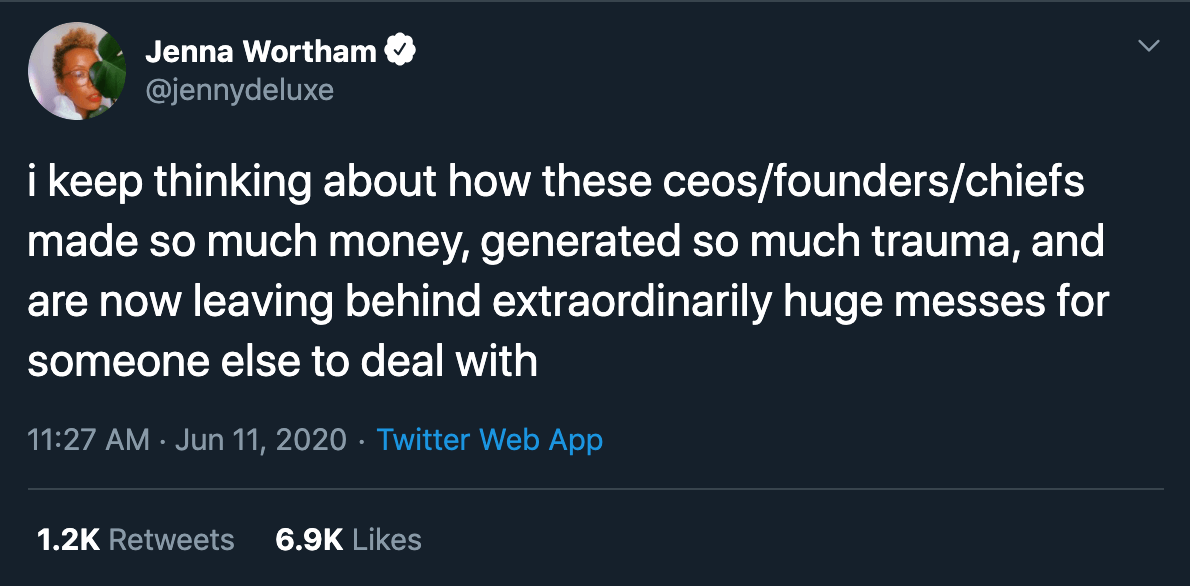

On the one hand, this reckoning is long overdue. On the other, these women stepping away from their leadership roles does little to repair the harm they have perpetuated. As New York Times writer Jenna Wortham pointed out, these women didn’t just make mistakes. They made incredible financial gains while inflicting harm on others. Now they are stepping away, the implied expectation being that someone else will make it better.

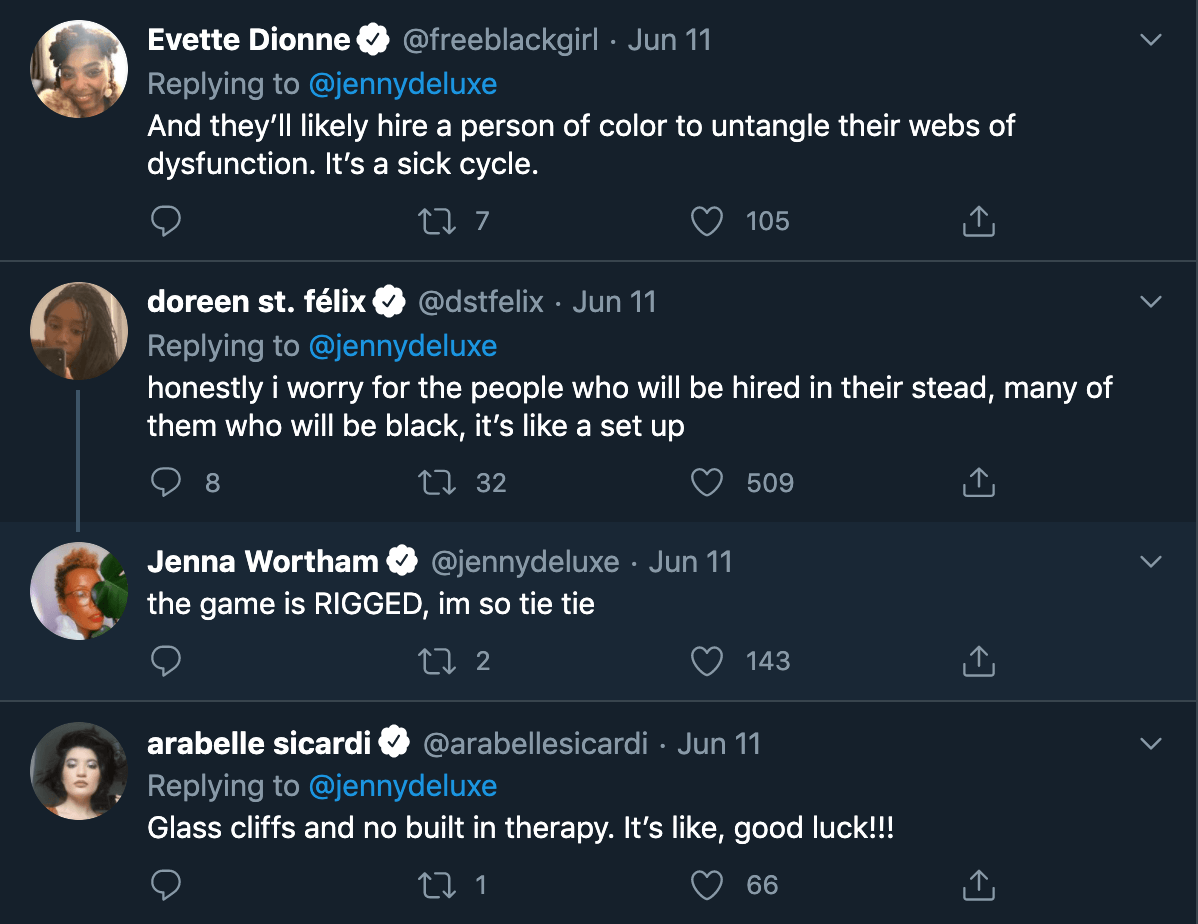

Some have mused that it’s likely these companies will appoint women of color to newly vacant leadership roles. The Wing, for example, has appointed Celestine Maddy as one of three women on its new “office of the CEO” team, which includes The Wing co-founder Lauren Kassan. But such precarious positions can act as a glass cliff—from the outside, it looks like the new leader has been elevated to a position of power, but given the mess she’s been handed, she’s actually been set up for a dangerous fall, without any built-in support to catch her.

It’s important to note that these resignations do not exist in a bubble. Women are not the only ones who have failed us. There are, of course, men who’ve resigned, too—and probably many more who haven’t who should. James Bennet, the former editorial page editor at the New York Times, resigned on June 7, following the publication of an op-ed titled, “Send in the Troops,” in which Senator Tom Cotton horrifically advocated that the government should use the military to suppress protests demanding justice for George Floyd. Adam Rapoport, editor of Bon Appetit, stepped down on June 8 just hours after a photograph surfaced of him in brownface on Halloween of 2013.

Men can fail, too, and spectacularly at that. But those men never promised us a revolution. These women’s failures may sting a bit harder because they sold us promises of feminism, sustainability, and mental health awareness.

Gotch, for example, advocated for awareness of mental health issues by selling gold name-plate necklaces that read “anxiety” and “depression.” Proceeds from these sales currently go to a mental health charity, but it’s impossible to ignore the fact that these necklaces afforded Gotch a different kind of capital—a way to signal that by buying from her larger brand, customers could be assured they were bringing joy and comfort to those who are suffering. Meanwhile, Gotch allegedly made openly racist remarks on a regular basis. Former employees complained that working at Ban.do caused them tremendous emotional distress.

Similarly, The Wing’s IRL spaces were filled with feminist slogans and merchandise. The Soho location had a room named for Black trans activist Marsha P. Johnson. Their Instagram account meticulously documented events where women of color took the lead and were celebrated. Yet, behind closed doors, former staff report that they were treated horribly. Women of color were being handed the mic in public while their counterparts in the kitchen and on the floor were being forced to sign NDAs. Following Gelman’s resignation, the current staff of The Wing staged a digital walkout. Employees shared a message to their social media accounts declaring, “Simply put, The Wing doesn’t practice the intersectional feminism that it preaches.”

The Wing employees told Fortune, “Ninety-three percent of The Wing’s employees, or 67 out of 72 workers, signed the petition.” They did not, however, share their list of demands.

The former staff of The Wing responded in turn, creating their own Instagram and Twitter accounts, @flewthecoup, where former “space staff” employees—those responsible for cleaning, kitchen work, and front desk services—who were let go when The Wing shuttered its doors in March due to the coronavirus pandemic, shared that they had not been consulted before the walkout and had thus once again been excluded from the narrative.

These former workers also created a petition which included their own list of demands.

While the voices of those critiquing these brands have grown louder, and their demands have been specific, the women receiving this criticism have been evasive and increasingly silent. When they have spoken, their responses have been lackluster at best.

Aflalo, Cohen, and Gotch have all issued apologies that point to their ignorance as the culprit before going completely silent.

Aflalo wrote on behalf of her larger team, “Unfortunately, the way we have practiced diversity in the past has been through a ‘White gaze’ that falls too close to ignorance.”

Cohen took a more personal tack, stating, “…I’ve fallen short here. That’s because this is more than just an exploration of my feelings. It’s my ignorance. Ignorance is part of the problem.”

Similarly, Gotch wrote, “I am guilty and not only am I guilty, I have been so ignorant and so insulated by the ease and comfort of my white privilege, that up until just a few days ago, I would have passionately and sincerely denied negatively impacting others.” Shortly after issuing her apology, Gotch deactivated her Instagram completely.

Gelman, meanwhile, has yet to publicly address her decision to step down. Her last post to her well-followed Instagram account is simply a black square, accompanied by the hashtag #blackouttuesday.

You could, of course, argue that these women are right and their ignorance is indeed to blame. But to leave it at that lets them off the hook easily. They have failed to describe their missteps and therefore they offer us no roadmap as to how to do better. By failing to own their active part in a system that perpetuates so much harm, they leave the door open for more harm. By going silent and stepping away, they remind us not that they are flawed or humbled, but rather, that they have the freedom to do so.

It’s possible that they are right, and their severe blindspots make them ill-suited for the kind of work necessary to build better brands and communities where racism and mistreatment are no longer tolerated. But these women had massive followings and influence. By walking away, they set a poor example for the other privileged women who admired them.

Ultimately, the unanimous sight of “I can’t” points to a troubling pattern. When rich, powerful white women are held accountable for their actions, their privilege allows them to retreat into a cocoon of relative comfort and ease. They can do exactly what Black people in our country cannot. They can opt out.