If you want to celebrate how popular your favorite video game is, even if it’s just another way to brag to friends, good luck finding the information.

At the 2015 Game Developers Conference, Ars Technica’s senior gaming editor Kyle Orland revealed a method he devised to figure out what games people buy on the PC game distribution service Steam. Orland can tell you what games people are playing and for how long, and whether people actually play the games they buy at all.

There’s a catch, though. All of this information is only a best guess, using statistical calculations while trying to account for the definite errors Orland knows are in the data. Orland’s best guess is better than anything gamers can get their hands on, however, unless they are willing to spend a lot of money.

Even experienced video-game journalists like Orland, who has been covering the industry for more than a decade, lack reliable, specific, and frequently updated sources of data for video game sales.

“It’s not like this in most other entertainment media,” Orland said. “Nielsen, for instance, provides ratings literally overnight for TV shows and makes the headline numbers very public in publications like Variety. Theaters and studios provide box office estimates every weekend for movies. … There’s Billboard charts for music, there’s the New York Times Best Sellers list for books, etc. etc.”

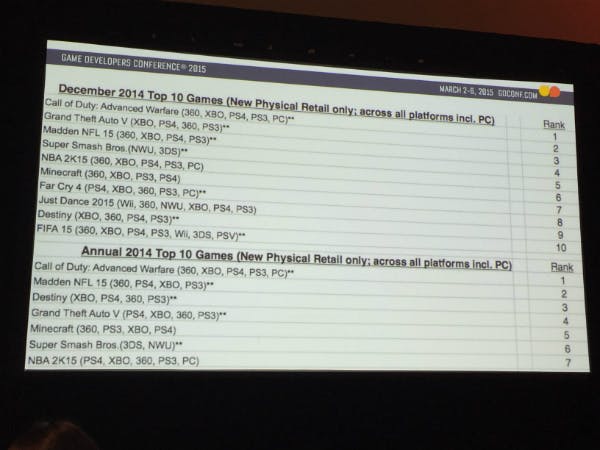

For games, the NPD Group tracking firm sends a top 10 list to the media every month. The list is based on a sampling of U.S. retail outlets and electronic sales. Getting more details than that costs a lot of money, and the people who pay for the data are contractually obligated not to share it with anyone else. NPD Group’s top 10 lists give reporters and industry watchers an idea as to what’s popular, but that’s about it.

“To get more details in the games business, we usually have to rely on self-reporting from publishers,” Orland said. “You only hear about it when it’s good news. You don’t hear about the triple-A game that flops.” And even when a game is successful, publishers may not share the information. It might be out of fear of competitors realizing how rich the market is for a particular type of game. It may be nothing more than deciding not to share data if no one else is.

Steam, on the other hand provides a consistently updated list of what the top games are on the service, measured by how many people are playing a certain game. The availability of the information made Orland wonder what other kinds of data he could mine from Steam. It turned out that the holy grail of game-sales information had been right under Orland’s nose for years.

If you play games on Steam, your public profile includes a tab that lists all of the games you own. That data is publicly available by default for any Steam user. Users have to adjust their privacy settings for this information to be hidden from public view.

According to Valve Software there are 125 million active Steam accounts. Orland estimates that the number may be around 220 million, based on analyzing unique Steam user IDs. That’s a lot of data for one person to crunch.

Random sampling, like the polls used by media outlets to gauge how Americans are voting during elections, solved Orland’s problem and became the basis of Ars Technica’s Steam Gauge program. When Orland compared his results to self-reported numbers from game publishers and information that publishers shared with him privately, the Steam Gauge numbers weren’t very far off.

Orland eventually gained Valve’s cooperation, after the site’s legal department had a look at what he was doing. Now Orland uses publicly available software developed by Valve to gather information about who is playing what on Steam. Even in the rough analysis, Orland’s data has yielded some crazy results.

-

For most games on Steam, almost half of the people who own the game have never actually played it. Orland attributes this mostly to game bundles and Steam sales, where games are very inexpensive to buy. Players create backlogs of games to play at some future date.

-

More than 25 percent of all game copies registered to players on Steam have never been played at all.

-

The top 13 most played games on Steam, which are only 0.2 percent of all the games available on Steam, account for close to 50 percent of the time players spend playing games on Steam

-

The most-played games on Steam, measured by mean hours per owner, are Football Manager 2014 and Football Manager 2015.

Orland knows his data isn’t perfect. Games like Dota 2 and Team Fortress 2 don’t factor into his estimations at all, because the information isn’t available. Those are two of the most popular games on Steam.

Orland also knows that Steam represents between 70 and 75 percent of the global PC gaming market, so numbers gleaned only from Steam can’t provide an accurate picture of how the entire worldwide PC gaming market is behaving.

Even with all the caveats and the margins for error, Orland’s Steam Gauge system provides data that is consistently updated and robust enough to measure things like the relationship between Metacritic ratings and Steam sales. Orland hopes that someday he can measure the effect of the aforementioned Steam sales on what games Steam users buy and what games Steam users buy together in bundles.

You can see detailed breakdowns of all the information Orland presented at GDC here. If you want to help Orland continue to gather his data, keep your Steam profile information public.

Photo by frankieleon/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)