It made perfect sense that I was up $80 in blackjack. Riding shotgun, I drove around New Jersey for 16 hours last Thursday and Friday night, dropping a few hundred dollars of someone else’s money into an online casino. I was a tester, tasked with making sure the bets were possible in the first place. The $80 was never mine to keep.

Just nine months after Gov. Chris Christie signed into law a bill that would allow casinos to offer online bets, New Jersey is set to usher in a new era of gambling in the U.S. on Nov. 26.

Last week, Ultimate Casino offered me a job to help test out the one of the one of the key components of the plan: the great firewall of New Jersey, a digital fence wrapped around the state in order to keep outsiders from gambling. If the wall failed, the house, in essence, would lose—and more than a billion dollars in bets would have to wait.

…

To make sure only people in New Jersey can gamble in the state’s online venues, casinos are using a technique called geo-fencing to build a virtual perimeter around the Garden State. It works by tracking a gambler’s cellphone, IP address, and Wi-Fi location to continuously monitor exactly where the bets are coming from. Take a wrong turn into New York, and you’ll be locked you out of a New Jersey casino’s digital doors.

That’s because to gamble in the first place, you’ve given the casinos an extraordinary power to track your location. You have to download a small browser plugin from a company, such as Loki, that has been contracted by sites such as Ultimate Casino and Tropicana Casino. Unlike most other geolocation software, the plugin checks Wi-Fi data to produce a very accurate picture of where your network is.

After that, you have to hand over a working cellphone number and agree, in practice, to have your phone’s location continuously tracked by casinos whenever gambling. A company called Locaid contracts phone carriers like AT&T to provide the location data to casinos within seconds of the request. This data can be used to paint an impressively complete picture of gambling habits, especially for professionals. Their entire working lives are mapped out and saved. That’s an incredible amount of personal information, but it’s the implicit cost of entry to gamble online in New Jersey.

The final tool in the casino’s belt is the Internet protocol (IP) address, a far more pedestrian and occasionally inaccurate tool for determining location. An IP address shows the network you use to connect to the Internet, but it can often relay faulty information, as it tends to be routed all around the country. When combined with the other methods, however, it adds a strong layer of redundancy.

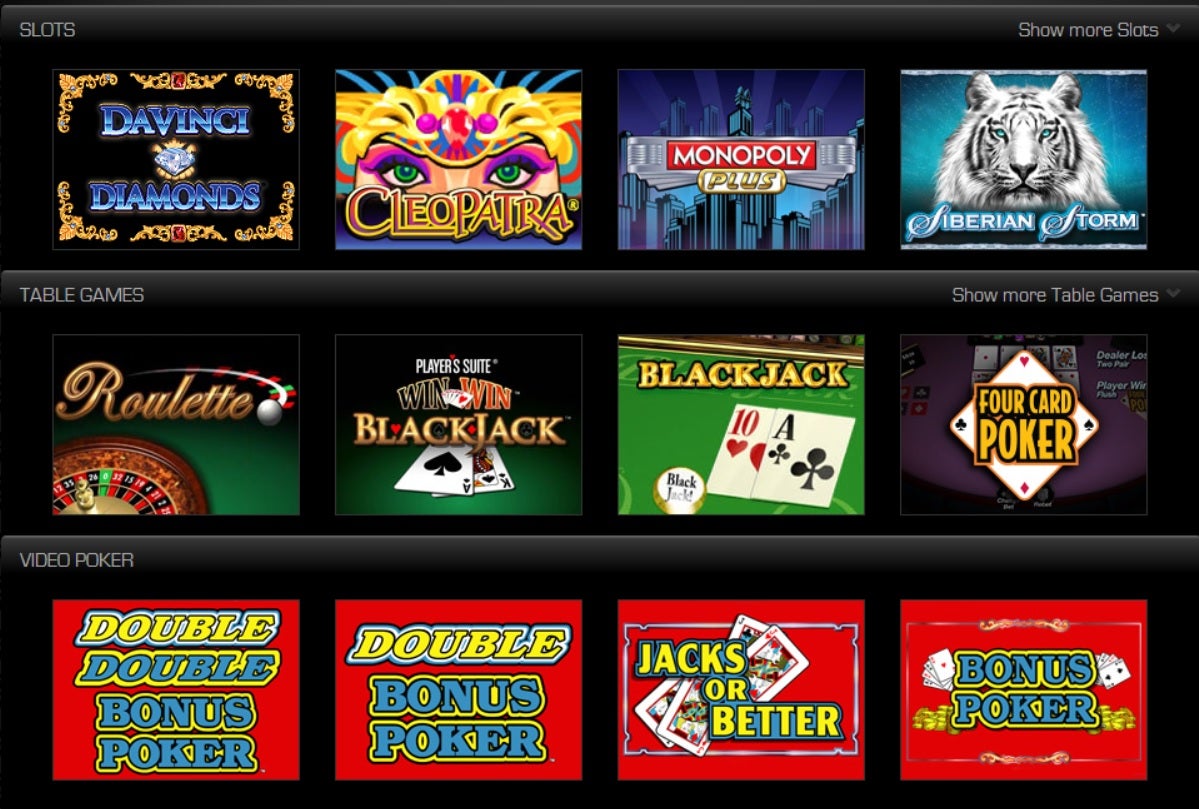

Screenshot of UCasino.com

In addition to preventing location fraud, the websites have to be able to catch identity fraud. To prove they were up to the task, the casinos had to commit a bit of fraud themselves. With regulators literally looking over their shoulders, casino employees attempted to register more than 50 dead and underage people using their social security numbers without permission. When their systems denied each fraudulent applicant, the websites were given another stamp of approval.

…

For over a dozen licensed sites with 500 early players each, testing on Thursday and Friday started out rocky.

All day Thursday, the Tropicana failed to register new phone numbers for the test gamblers. The Borgata, a major Atlantic City casino, was unable to verify social security numbers and didn’t open until several days past the beginning of testing. Ultimate Casino had trouble picking out users locations. The only site with good reviews out of the gate was the World Series of Poker site, run in partnership with Caesars.

By late Thursday, only about four people had successfully made bets on the Ultimate Casino site, despite hundreds of sign ups. Starting in Newark, New Jersey’s biggest city, I tested and failed to register for almost every gambling website. Many casino employees pulled all-nighters in their Las Vegas and Atlantic City offices or drove cars around New Jersey to fix the problems.

I finally took several of the sites for a real test drive late on Friday on a trip designed to test the website’s ability to take bets in and out of New Jersey. I started my trip in Newark where a $3 blackjack hit paid off. We drove to Union and then Paramus, both in the state’s north, and the hits kept coming. Identity and location verification takes only a few seconds before you’re placing bets. Closer to the New York border in Jersey City, the websites began to deny my bets about five miles before they should have. By the time I drove to Manhattan, I hadn’t been able to gamble in an hour.

Online gambling launches this Tuesday. Slowly but surely, things have begun to work as expected. But the system is far from perfect.

…

As a fence surrounding 8,721 square miles, the margin for error is small. If the digital wall is a mile off to the east, a chunk of Manhattan’s daytime population of 3.1 million people could suddenly place illegal bets. If a glitch opened up the wall a mile to the west, a million Philadelphians could pull up chairs at the blackjack tables.

This is a problem the geolocation programs can’t practically solve, so rather than risk being too big, casinos went small. As a result, thousands of people within about five miles of the New Jersey state border will be blocked from gambling online even if, legally, they ought to be allowed. Some reports say that residents over 10 miles inland were denied during testing. If that’s true, millions in the state can potentially face issues when gambling.

Even outside the state, people will undoubtedly break past the wall. In a 2011 criminal case, the United States pushed three of the biggest online poker sites that had been operating with minimal oversight and little regard for the law out of the country. The government sought $3 billion in assets. Ever since, professional gamblers have been getting around digital barriers like the one in New Jersey to make make their living.

Getting by the system is simple on paper. To beat the phone tracking, a gambler simply needs to own a phone in the state. In Nevada, whose borders are protected by a similar digital barrier, a number of residents charge a fee for shelf space so that pro gamblers can always have a working phone in the state. They add on extra fees if they ever have to answer the phone—if for instance, casinos call for verification codes or otherwise try to check in on the legitimacy of the phone.

To beat the Wi-Fi and IP location software, gamblers can pay for personal proxy servers, a bit of Internet cloak and mirrors that makes it look like you’re logging onto the Internet from another location entirely. With a proxy, a bet placed in Rio de Janeiro could look like it was placed in Oceanside, N.J. Casinos do keep tabs on—and block—publicly listed proxies, so gamblers are forced to set up private systems. Altogether, a good private proxy can cost $25 per month.

Most gamblers won’t go through the time and trouble to break the wall. Professional gamblers, on the other hand, are already scouting out shelf space for their cellphones. For them, the cost is well worth the investment.

Photo via Images_of_Money/Flickr