On Feb. 1, Iowa will once again land in America’s spotlight as it hosts the first major electoral event of the 2016 election.

For many political junkies, the combined results from Iowa and the primaries in New Hampshire on Feb.9, will be the first real hint outside of polls as to whether Donald Trump has enough holding power to win the Republican party’s nomination in July. Iowa and New Hampshire will also tell us whether Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders are as neck-and-neck as political pundits believe. The results in those two key states will kick-start a long and convoluted primary season as states narrow down which candidates for president they hope to see on the ballot in November 2016.

And it all begins in Iowa. But what are the Iowa caucuses? And does Iowa really matter as much as everyone seems to think it does?

What is the history of the Iowa caucus?

The timing of Iowa’s caucuses is purely strategic. Iowa’s decision in 1972 to hold its Democratic caucus in January made it the first stop on the campaign trail for many. Former President Jimmy Carter’s successful courting of Iowa Democrats in 1976 further escalated the state’s importance in national politics.

For Democrats, victories in Iowa could be pivotal, as they were for John Kerry in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2008. But for Republicans, Iowa is at best a wash. As the American Prospect notes, Iowa Republicans are a poor representation of Republicans nation-wide. Why? Evangelical Christians have a larger-than-average presence in Iowa, which is why Iowa victories for former Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) in 2012 and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee in 2008 did not translate to further success down the road.

As Newsweek notes, Iowa has predicted the Republican candidate for president only twice. When Iowa Republicans held their first caucus in 1980, Ronald Reagan actually lost.

Why do the Iowa caucuses matter this year?

The Iowa caucuses this year will do the important task of narrowing down an already vast field of Republican candidates. While Trump is leading in the polls in Iowa, he does not have a majority. So, as we head towards Super Tuesday (March 1), the question becomes, will Trump win when stacked up against one other candidate, and not seven? Or, put another way, will enough non-Trump supporters gravitate to Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) or whoever holds the second-largest chunk of delegates to ensure Trump’s loss?

For Democrats, the Iowa caucuses could be a game changer. As the Wall Street Journal reports, most of Sanders’ support is concentrated in college towns. Could enough of the youth vote show up to grant Sanders an upset victory? The Des Moines Register has already endorsed Clinton in Iowa, but that could be the kiss of death for the former secretary of state. The liberal newspaper endorsed Clinton back in 2008 and John Edwards back in 2004, in both cases the paper’s chosen candidates lost.

What happens at an Iowa caucus?

As it happens every four years, Iowans will gather in high schools and public libraries assigned by their precinct to take part in a process that only vaguely resembles voting. Different from elections, caucuses are more like a series of local meetings held by the political parties themselves to determine how many delegates they should grant presidential hopefuls.

Also, voters aren’t voting to nominate candidates directly, but to send delegates on their preferred candidate’s behalf to the national conventions.

Both parties will further narrow down their pool of delegates in county and state conventions. The final Iowa delegation will attend their party’s respective presidential conventions in July, where they will pick their nominee.

Confused yet? It gets worse.

Democrats and Republicans meet separately and listen to supporters for each of their party’s candidates to make their case. Then, something happens that has struck up much controversy: Both parties vote differently. Republicans vote by secret ballot while Democrats split into “presidential preference” groups that must disband and join another candidate if there aren’t enough to meet the threshold.

Iowa’s Democratic party goes into more detail on their site:

“If a preference group for a candidate does not have enough people to be considered ‘viable,’ a threshold set at the beginning of the night, eligible attendees will have an opportunity to join another preference group or acquire people into their group to become viable. Delegates are then awarded to the preference groups based on their size.”

In other words, if there are 40 Clinton supporters, 30 Sanders supporters, and 10 O’Malley supporters at your caucus site, the 10 O’Malley supporters that fall below the night’s threshold will have to disband and join either one of the two other groups of supporters.

If you’re a Republican, you will voice your preference for a presidential nominee on a written ballot. Results are then tabulated and sent to each party and reported to the media.

When does the Iowa Caucuses start? And when will we know the winner?

The Iowa caucuses are scheduled to begin at 7pm ET. While the voting process sounds even more tedious than the general election, there’s a fair chance we’ll know results early. As the Washington Post points out, results were called in 2008 for Barack Obama and Mike Huckabee by 9:30pm ET. But in 2012, a last-minute surge by former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum—who’s also 2016 GOP candidate—lead to his victory not being declared until eight days later.

Iowa Democrats are testing out a new mobile app that will report results from each of the 1,681 precincts to the Iowa Democratic Party. Given it’s their first time experimenting with the new technology, there’s no way of knowing if it will expedite or further delay the process.

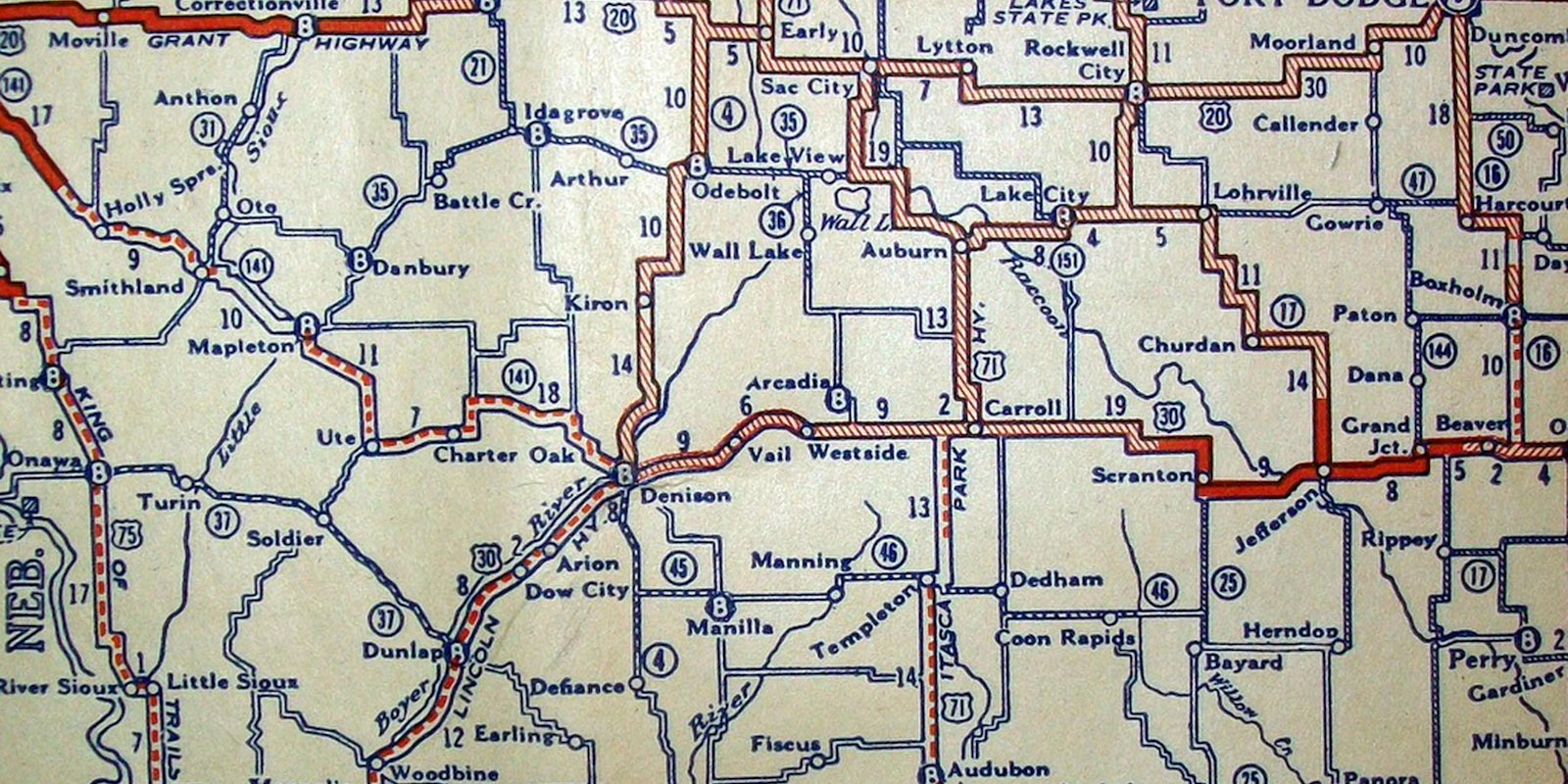

Photo by davecito/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)