This weekend, the controversial whistle-blowing organization WikiLeaks released a pair of documents produced by the CIA. The documents, leaked by an unidentified source and dated from late 2011 and early 2012, serve as a guide for covert agents attempting to get through foreign airport security without blowing their cover.

One of the Central Intelligence Agency documents explained the procedures in a general sense, the other specifically focused on issues affecting the Schengen Area, a zone of 26 European nations that have abolished internal passport controls. This region contains American allies like Germany, France, Poland, Italy, Spain, Greece, and Sweden.

“The CIA has carried out kidnappings from European Union states, including Italy and Sweden, during the Bush administration,” said WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in a statement. “These manuals show that under the Obama administration the CIA is still intent on infiltrating European Union borders and conducting clandestine operations in E.U. member states.”

Assange is currently holed up in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he is wanted for questioning over sexual assault allegations.

Secondary screening occurs when airport security officials flag individual passengers for significant additional scrutiny—an invasive process many Americans will experience this holiday season. Selection typically occurs at the discretion of the security officers and can be triggered by anything from irregularities with a traveler’s documentation to random selection.

“The resulting secondary screening can involve in-depth and lengthy questioning, intrusive searches of personal belongings, cross-checks against external databases, and collection of biometrics—all of which focus significant scrutiny on an operational traveler,” the report reads.

A comprehensive list about what triggers secondary screening doesn’t exist, largely because such procedures vary from airport to airport. However, being pulled out for secondary screening can often be the result of the visa application process required to enter many countries around the world, such as Russia and China. Visa applications ask for a whole host of personal information, ranging from height to work supervisor’s phone number, that is often checked against external records, such as those provided by the hotels or government intelligence agencies. If things don’t add up, it could be an indicator that the traveller is a terrorist, drug smuggler, or even a spy. “Confirmed or suspected government or military affiliation almost certainly raises the traveler’s profile,” the report notes.

Even in countries that don’t require visas for relatively short stays, travelers can still be pulled out for secondary screening, the report notes, if the screener “suspects that something about the traveler is not right.”

The report says that some foreign airports use cameras, one-way mirrors, and undercover officers to look for passengers “displaying unusually nervous behavior,” such as “shaking or trembling hands, rapid breathing for no apparent reason, cold sweats, pulsating carotid arteries, a flushed face, and avoidance of eye contact.”

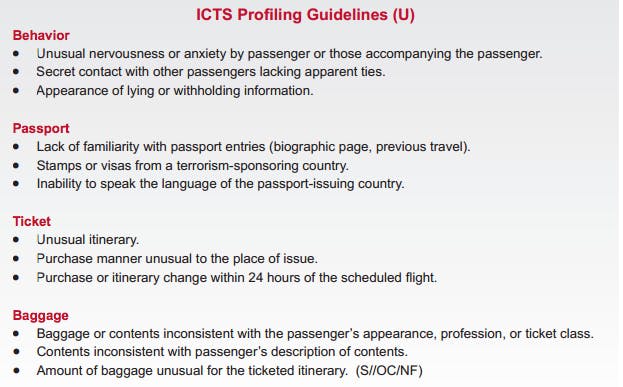

Here is a list from the report of things can potentially trigger a secondary screening:

Sometimes, being randomly pulled out for secondary screening serves an ulterior motive. The document mentions a 2010 report that found that the manager of Somila’s Mogadishu International would regularly pick one passenger from a flight and accuse them of breaking the law as a way to extract a bribe from the unlucky target. A similar thing also reportedly occurred at Chittagong Airport in Bangladesh.

For the average traveller, being selected for secondary screening can be time-consuming or, in the case of a Mogadishu-like shakedown, expensive. For an undercover CIA agent trying to enter a country undetected, it’s another matter entirely. The report explains that “the combination of procedures available in secondary, a stressful experience for any traveler, may pose a significant strain on an operational traveler’s ability to maintain cover.”

Airports deploy their most experienced agents for secondary screenings to determine if a traveler isn’t who they say they are, or if that person’s intention in the country maybe something considerably more underhanded that simple tourism—say, espionage. During that process, travelers usually can be held for hours without access to the embassy of their home country or any other outside assistance.

The report notes that the Estonian Border Guard Service gives people selected for secondary screening the chance to log into their social media accounts like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn to prove their identity.

“Security officials might also expect a sales or marketing traveler to have a Twitter account,” the report explains. “The absence of such business-related Web accounts probably would raise a business traveler’s profile with officials.”

As such, the guide recommends undercover agents spend time building up believable social media histories that compliment their cover stories. The report adds that devices like smartphones can pose a problem because they typically require a link between the device and someone’s real-world identity. If a screening agent can dig through a smartphone to find that data, it has the potential to blow the cover of an agent traveling under an alias.

The key to surviving a secondary screening, the report notes, is having a “consistent, well-rehearsed, and plausible cover” backed up by everything from the contents of one’s luggage to their hotel reservations to their “pocket litter.”

Rehearsal is key because it allows undercover agents to rattle off their stories without giving off tells, such as using long pauses to delay before answering questions, fidgeting, or using qualifying phrases like “to be honest” or “swear to God.”

The most important takeaway from the report is the importance of maintaining cover no matter the circumstances, since sticking to even an unconvincing lie could allow an agent to pull through in the end.

In one incident during transit of a European airport in the early morning, security officials selected a CIA officer for secondary screening. Although the officials gave no reason, overly casual dress inconsistent with being a diplomatic-passport holder may have prompted the referral. When officials swiped the officer’s bag for traces of explosives, it tested positive, despite the officer’s extensive precautions. In response to questioning, the CIA officer gave the cover story that he had been in counterterrorism training in Washington, D.C. Although language difficulties led the local security officials to conclude that the traveler was being evasive and had trained in a terrorist camp, the CIA officer consistently maintained his cover story. Eventually, the security officials allowed him to rebook his flight and continue on his way.

As WikiLeaks notes in a press release about the leak, the anecdote raises far more questions than it answers. Primarily, what was a CIA official doing traveling into the E.U. with traces of explosives on his clothing?

The second document is specifically focused on helping agents sneak their way into the European nations of the Schengen Area—specifically in the context of the prevalent use of biometric screening techniques in place at many national entry points.

The report’s message, however, is largely not to worry. “The European Union’s Schengen biometric-based border-management systems pose a minimal identity threat to U.S. operational travelers because their primary focus is illegal immigration and criminal activities, not counterintelligence, and U.S. travelers typically do not fit the target profiles,” the report reads.

Even so, biometric screening is something that clearly has the CIA concerned.

If Americans were subjected to biometric analysis, it would be far more difficult for them to maintain their covers. “The European Commission is considering requiring travelers who do not require visas to provide biometric data at their first place of entry into the Schengen area,” the report insists, “which would increase the identity threat level for all U.S. travelers.”

Photo by David Benbennick/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)